Article Note: This is the first installment of a two-part series on laneways, see Part 2.

“We need an approach that will see our cities repurposed by getting more from less: a re-timetabling rather than the grand engineering projects of the twentieth century.” — Rob Adams, Director City Design, City of Melbourne

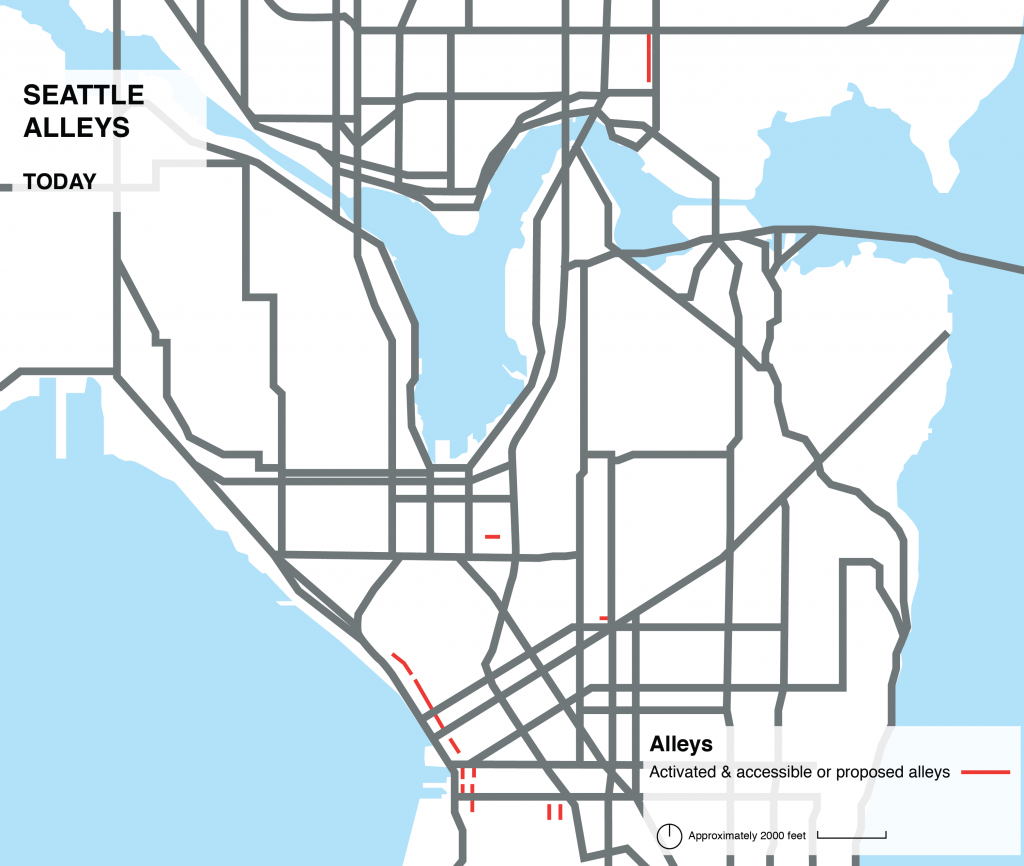

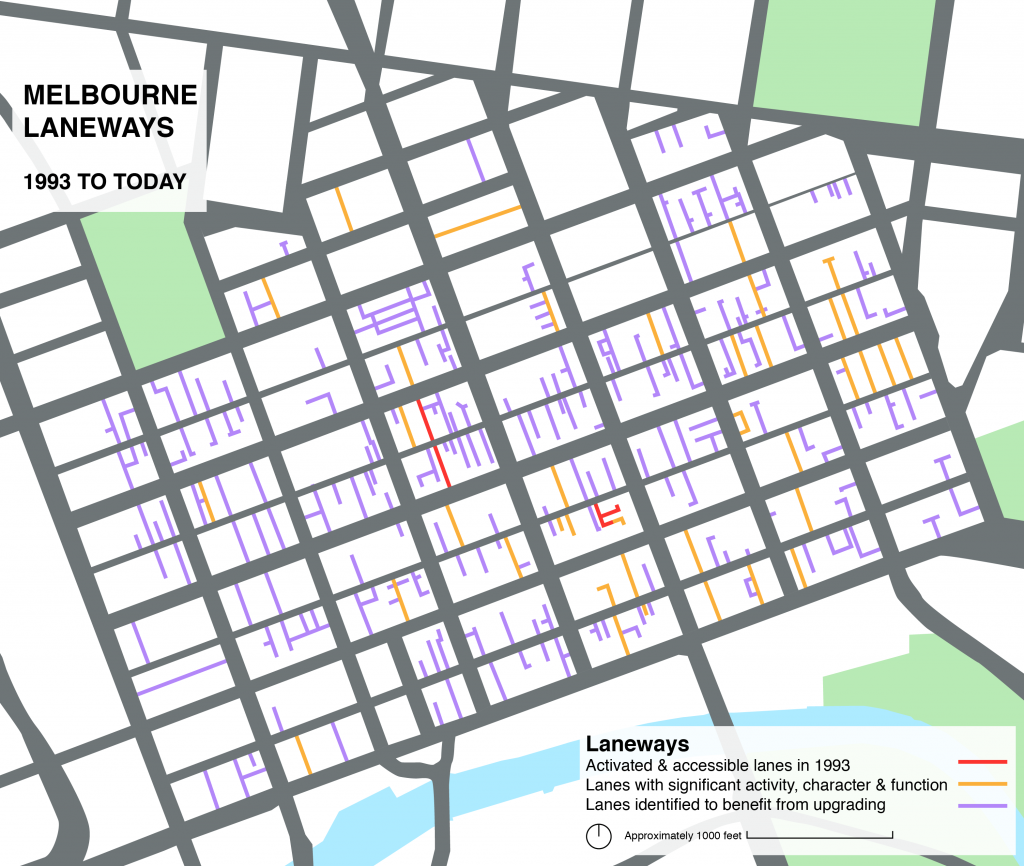

Only a few decades ago, the intricate network of laneways in Melbourne, Australia, carved into the street grid by property owners for access, sewerage, and waste disposal during the Victorian era, were overlooked and devoid of life. As a result of incremental initiatives, Melbourne’s laneways are now world-renowned — transformed into inviting passages, lined with an enviable mix of alfresco eateries, unique bars, boutiques, street art and residences. Given growing interest and efforts to enliven alleyways in Seattle, the revitalization of Melbourne’s laneways provides an example of re-envisaging these spaces as public assets.

Source: Alley Network Project / SvR Design Framework

The Seattle Times

In 1994, only 300 meters of laneways in central Melbourne were considered to be activated and accessible. But within 10 years this had increased 10 fold to approximately 3km. This change is significant. The City of Melbourne’s Walking Plan (2014) estimates increasing walking connectivity of the central grid just 10%, generates an additional $2.1 billion per annum to the local economy. Melbourne’s lanes are unique public spaces, providing important north-south connections as well as interesting places for social interaction, outdoor dining, live music, and art. They also provide a service function for waste management and car parking access.

Compared to main streets, the lanes are more conducive to a human scale, with narrow widths limiting vehicular access and favoring the buzz of pedestrian movement. There was no single policy or approach that led to the experience offered in Melbourne’s laneways today; rather, economic, social and cultural circumstances, coupled with state policy reform and urban design strategies to build upon the city’s assets and historic charm. Whilst Melbourne is now internationally renowned for the successful laneway revitalization, the City of Melbourne and State Government of Victoria delivered a suite of initiatives to improve the public realm over the long-term. In Seattle, there are several successful examples of activated alleyways as well as temporarily programming for events that demonstrate the potential for enhancing other parts of the network here.

Background

From the 1970s, Melbourne’s Central Business District (downtown area) was in decline, as it began losing residents and retail to the appeal of the suburbs — offering convenient access by car. A homogenous business center, empty beyond the working day, the vibrancy of the center was threatened. The city’s celebrated Victorian streetscape character was undermined by encroaching freeways serving commuters, the demolition of heritage buildings, and new developments in breach of height restrictions. Contemporary buildings dominated city blocks, eroding the laneways, which had become neglected spaces used for little more than garbage disposal.

In 1978, architect Norman Day reflected the growing community concern about the loss of Melbourne’s character, writing in an article for the Age newspaper, “Our planners should be reaffirming the notion of Melbourne as an arcaded city instead of allowing architects to allocate useless, wind-swept forecourts ‘for the public use’.”

By the 1980s, the population of the central city had decreased to just 2000 residents. The decline in light manufacturing and warehousing activity in inner Melbourne, and an oversupply of office space in the center, left many parts of the city vacant. New ways of thinking about the form and function of the core began to evolve. City and state leaders, designers, developers, and businesses started to recognize the importance of re-activating the central city to attract residents and business back. Melbourne’s laneways benefited from strategies to restore the public perception of the center and offer a more comfortable experience for people.

Public realm strategies

The City of Melbourne developed strategies to manage the changes affecting the city and mitigate the exodus of people and businesses. With a goal to reactivate the inner city, the Strategy Plan (1985) sought to reinforce Melbourne’s positive characteristics, while addressing the negatives. Streetscapes were graded according to quality, and heritage buildings identified, supporting the conservation process for significant places. The City established a goal to increase the central city population by 8000 residents over 15 years. To achieve this, the city directed attention and investment to the quality of the public realm.

The City’s Grids and Greenery strategy (1987) identified natural and constructed patterns of Melbourne, informing the development of urban design principles to reinforce these characteristics. The City focused on improving the pedestrian experience, establishing a program for widening sidewalks, planting more street trees, replacing unnecessary asphalt with green spaces, and installing additional street lighting. These efforts helped to reverse the downward trend in people living in and visiting the central city.

The City required new buildings to be built to site boundaries, discouraging large paved plazas, to maintain the street edge, and ensure a strong connection between buildings and the pedestrian on the street. A percentage of the street facade of new buildings were required to have active frontages, such as shops or businesses, to provide a visual or physical interaction between the ground floor and public space. This policy arguably supported small tenancies and continually increased retail spaces, ensuring a steady supply which played a role in maintaining competitive rents, offering opportunity for experimentation by diverse and independent businesses. The historic bluestone paving of Melbourne was preserved, or reinstated in sidewalks, most notably in the laneways. Across the City, these detailed design qualities, reflect the mantra of the City’s Director of City Design, Professor Rob Adams, “If you can design a good street, you have a good city”. With more inviting and interesting streets, laneways and public spaces for pedestrians to enjoy, people spent more time in them.

See Part 2 which discusses other factors which contributed to the activities on Melbourne’s laneways today, including liquor law reform, initiatives to encourage more residents to live in the central city, and public art, in addition to the benefits of the City’s public life research and contemporary development enhancing the laneway network.

Sarah is an urban planner and artist from Melbourne Australia, currently living in Seattle. She has contributed to diverse long-term projects addressing housing, transportation, community facilities, heritage and public spaces with extensive consultation with communities and other stakeholders. Her articles for The Urbanist focus on her passion for the design of sustainable, inviting and inclusive places, drawing on her research and experiences around the world.