Article Note: This is the first installment of a series on observations of people in Pike Place. Part 1 focuses on existing design features and transitory activity.

“…please look closely at real cities. While you are looking, you might as well also listen, linger and think about what you see” – Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961.

Pike Place Market is a Seattle landmark for locals and tourists, attracting 10 million visitors annually. As the longest continuously operating farmers market in the United States with hundreds of unique produce and craft vendors, the 9-acre precinct is one of the busiest places in Seattle. Overlooking Puget Sound and the Olympic Mountains, the Market is comprised of several buildings, some with multiple levels and entrances, which frame the main public thoroughfare of Pike Place between Pike Street and Virginia Street.

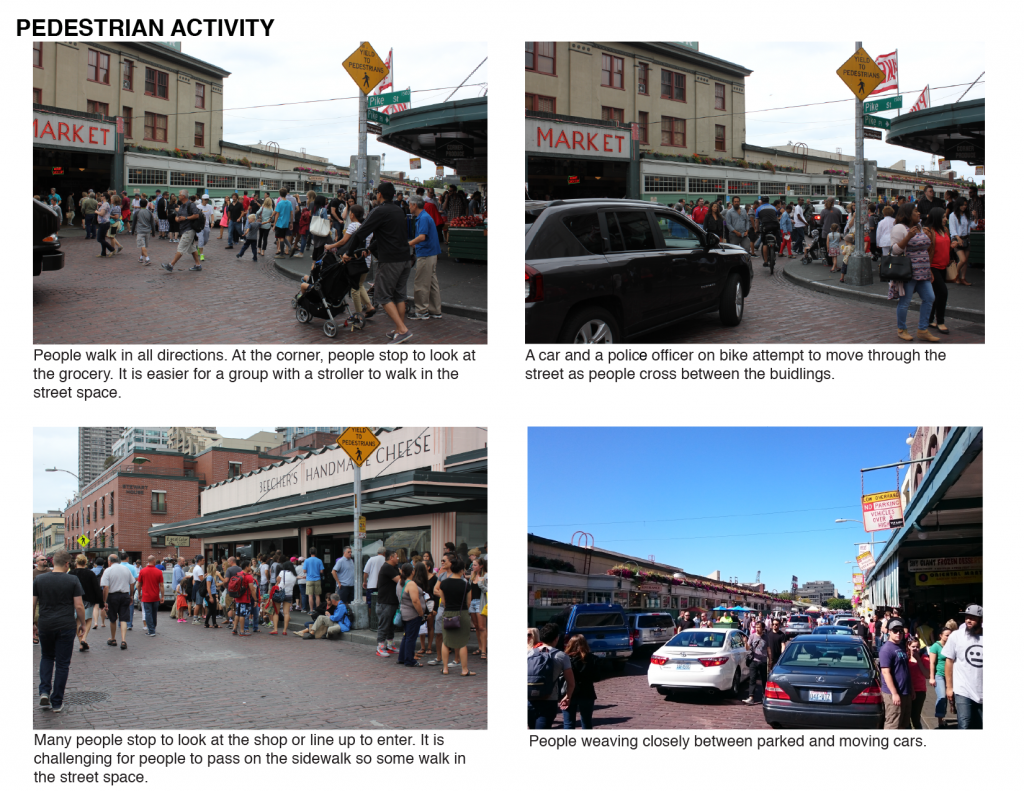

With substantial daily visitors, sidewalks in Pike Place are regularly crowded often with pedestrians spilling into the street which provides one-way vehicular access and some on-street car parking. This creates an interesting dynamic between people and cars, particularly affecting pedestrian ease of movement, comfort, and safety.

An article published on The Urbanist, which explored the idea of putting people first at Pike Place Market by banning cars, generated extensive discussion from readers sharing their perspectives. Some agreed that limiting car access would enhance the pedestrian experience whilst others articulated the importance of cars and parking for the viability of the Market. To contribute to discussions about the design of this public thoroughfare and pedestrian experiences, a series of short qualitative observational studies were conducted at Pike Place to better understand where people walk, sit, and stand.

Studying Public Life

The comments in response to the idea for restricting traffic at the Market highlights that people have different and subjective views on what constitutes a good or bad public space, making public life studies incredibly valuable. Public spaces support many human functions, including, but not limited to: socializing, exercising or playing, accessing light, fresh air or nature, and relaxing. Public life studies focus on the methodical observation and documentation of people in public spaces to better understand how a place is occupied, used, and enjoyed.

This research field emerged from the 1960s, with seminal observational studies by Jane Jacobs (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961), William H. Whyte (Street Life Project, 1971), and Jan Gehl (Life Between Buildings, 1971), among other notable researchers. Public life studies have been useful for documenting the relationships between environmental design and behavior to inform decision-making and design processes to improve places for people. They enrich our understanding of city life, particularly the quality, performance, and successfulness of a place as well as the needs of people. Such studies assist with documenting existing conditions, identifying issues, developing solutions, and evaluating the impacts of design interventions.

Observing people in public space is complex. City life is transitory with people moving and conditions changing constantly. There are extensive variables, such as architecture and design, weather, noise, smell, light, and shade as well as the number, location, and types of people using the space. In How to Study Public Life (2013), Jan Gehl and Birgitte Svarre share several simple tools to assist people to systematically study interactions between city space and people to enhance knowledge to improve places. The authors encourage people to go out in the city and “look and learn” how it works using different senses.

Pike Place Market Study

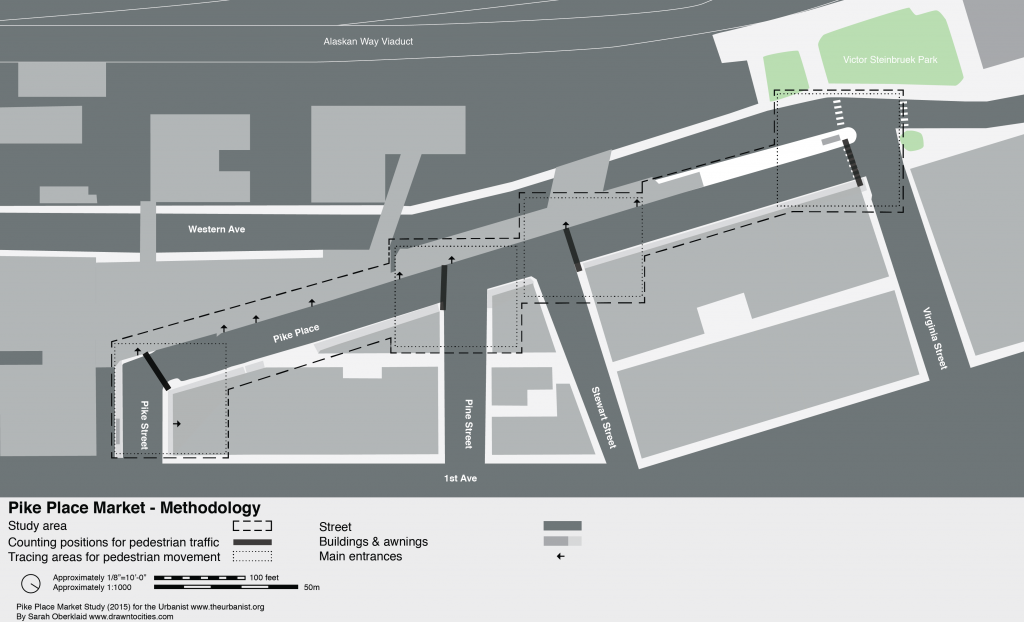

Simple and tested approaches by Gehl and Svarre were adapted to document pedestrian activity at Pike Place. Firstly, the existing conditions were observed to determine the study area and develop appropriate approaches for collecting data. The study focused on Pike Place, located west of First Avenue from Pike Street to Virginia Street. This area was selected as it forms the main public thoroughfare with brick paving distinctive from surrounding streets, has high pedestrian volume, and vehicular access and parking. The study did not explore Post Alley or Victor Steinbrueck Park because they are already pedestrian-oriented spaces in the Market precinct with minimal interactions from vehicles.

To provide a snapshot of pedestrian activity at the Market, several observational techniques were used, including: mapping, counting, tracing, and note-taking which was documented manually using pens, paper or base maps, and a stopwatch. The data was collected on two weekdays in July 2015. The study was conducted between 11am and 3pm on Day 1 with predominantly overcast and mild conditions and between 2pm and 5pm on Day 2 with sunny and hot conditions.

1. Mapping Existing Conditions: What are the design features of Pike Place?

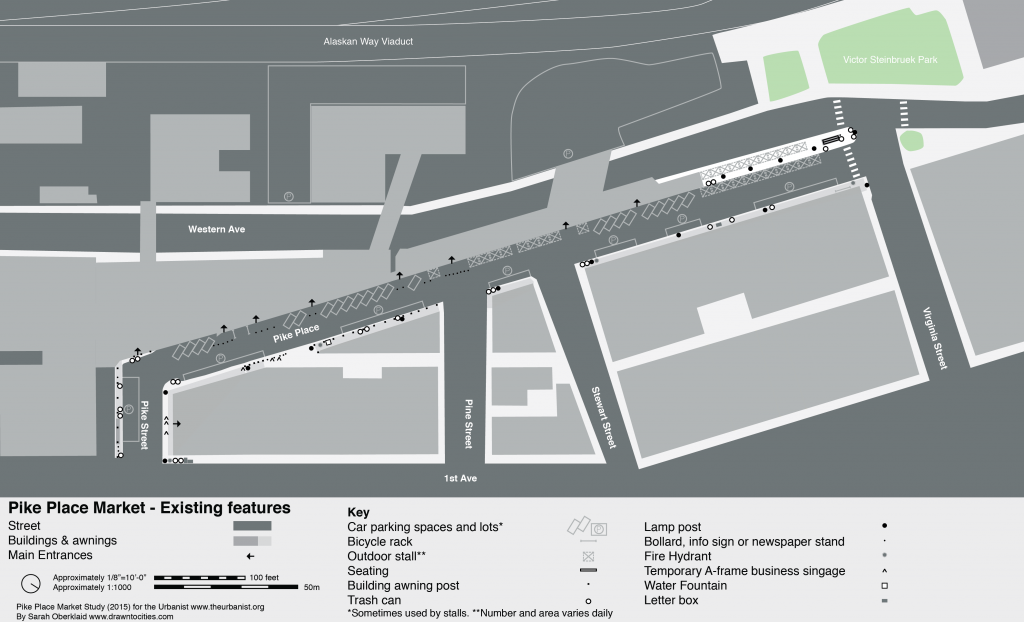

Understanding the existing features of a place provides insight into how behavior is shaped by the built environment, whether people’s needs are met, or if there are impediments to their movement or use of the space.

Impressions

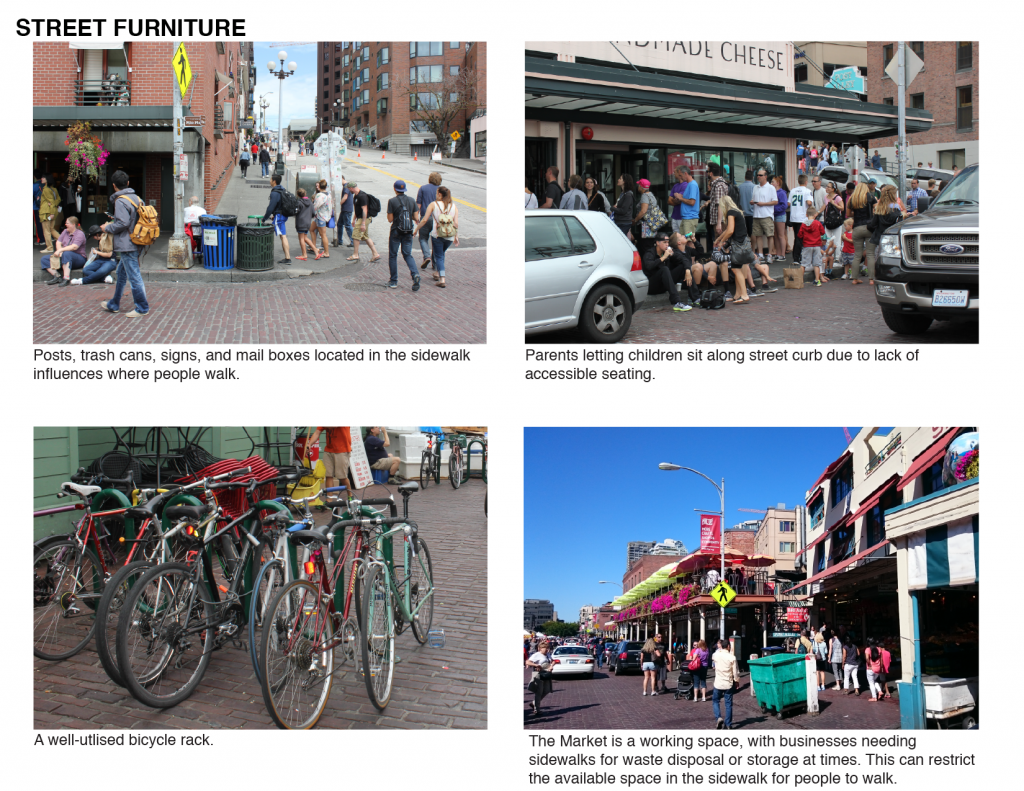

While there are sidewalks on both sides of Pike Street, they are only present on the eastern side on Pike Place. As a result, people can only walk in the parking or road space on the western side. Street furniture, such as building posts, trash cans, lamp posts, bollards, information and newspaper stands, fire hydrants, water fountains, and letter boxes encroach upon the sidewalks. This limits the space available for pedestrians to walk and consequently may impact their movement, especially when crowded.

Positively there are extensive awnings to protect pedestrians from the elements and several lamp posts for nighttime safety. Not all car parking spaces are delineated; however, there are approximately 50 spaces, some of which were utilized for extra stalls on Day 2. There are only three racks for bicycle parking. On both days, there were only two benches accessible for seating. Seating is located along the north-western end of Pike Place; however, these were being exclusively used by craft stallholders on both days. William H. Whyte observed in The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces that “[p]eople tend to sit the most where there are places to sit,” suggesting that when such seating is not available for public use, the opportunity for people to take the time to sit and enjoy Pike Place may be limited.

2. Transitory Activity

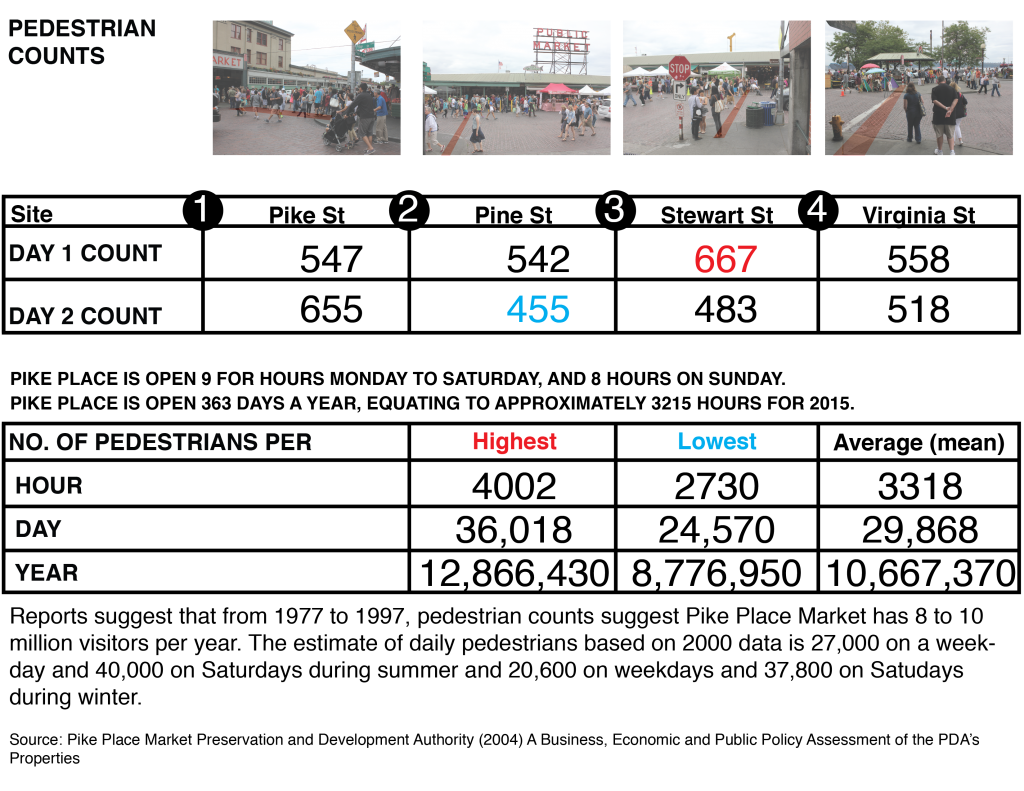

2.1 Counting Pedestrian Flow: How many people are walking at Pike Place?

Counting is a common tool in public life studies. Quantitative data is useful for comparing over time with different localities or under different conditions. Documenting how many or few people use a place provides insight into its successfulness.

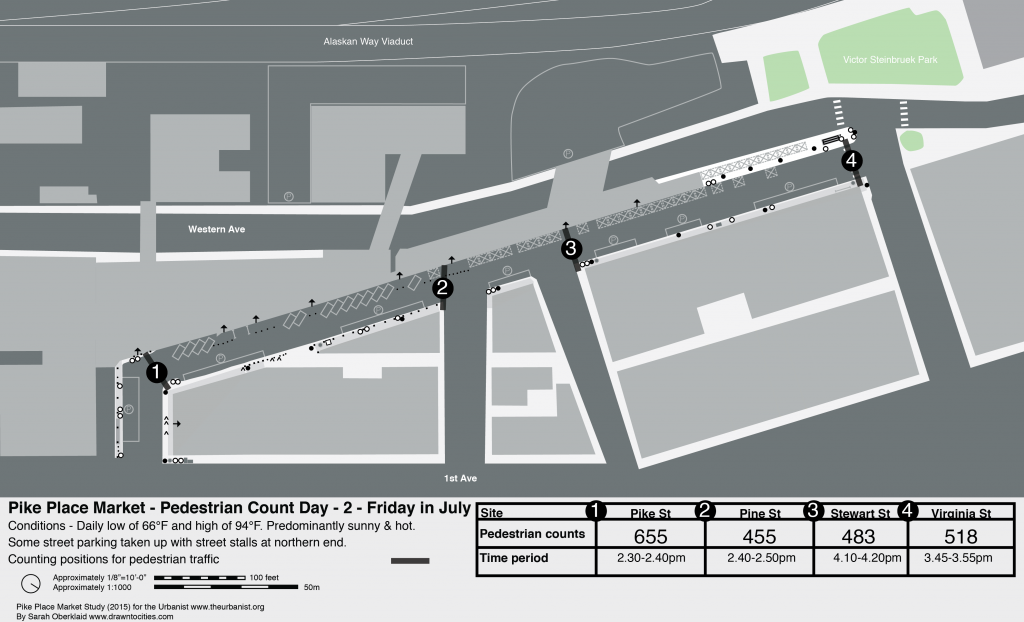

Approach

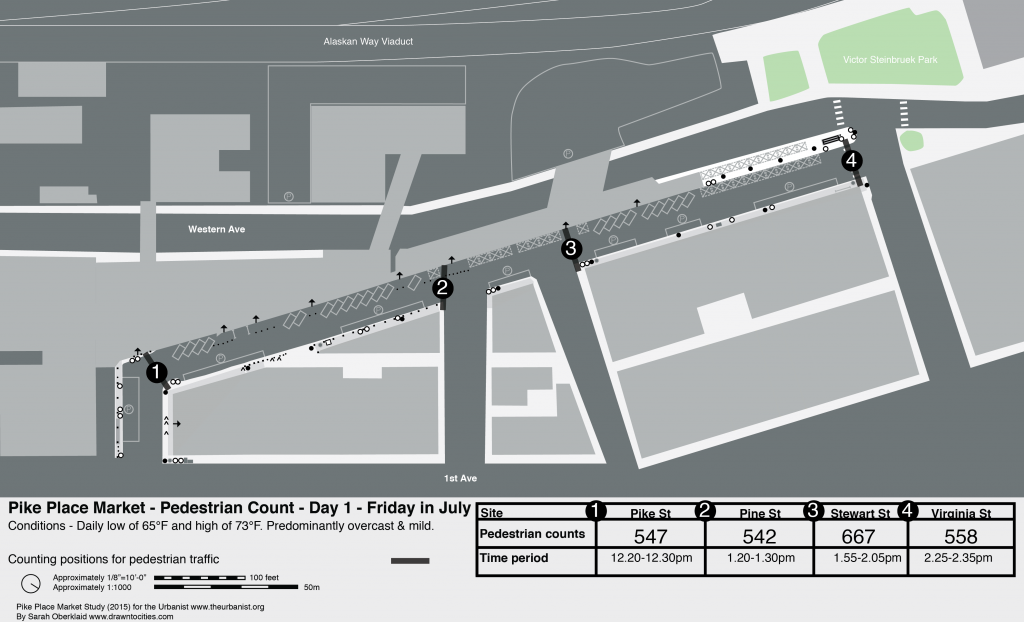

As shown on the map below, people were counted when they walked across an imaginary line at four different points. Each point was observed for 10 minutes, and although this is short, it provides a quick snapshot and an approach which can be easily repeated to get a richer data set. The four sites were selected because they intersect with one of the cross streets (Pike, Pine, Stewart and Virginia Streets) and provide an entrance into one of the Market buildings, or the open air craft stalls, creating high potential for connections inside to outside as well as interactions between pedestrians and traffic.

Impressions

Across just 10 minutes, a high level of pedestrian activity was observed with between 455 and 667 people passing each of the imaginary lines. This data was extrapolated to estimate the number of people per hour, day, and year. Although more data would need to be collected across different times of the day to get a more accurate estimate, the resulting figures are interestingly in the realm of the 27,000 average daily weekday visitors during summer and 8 to 10 million visitors per year reported in a 2004 study for the Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority.

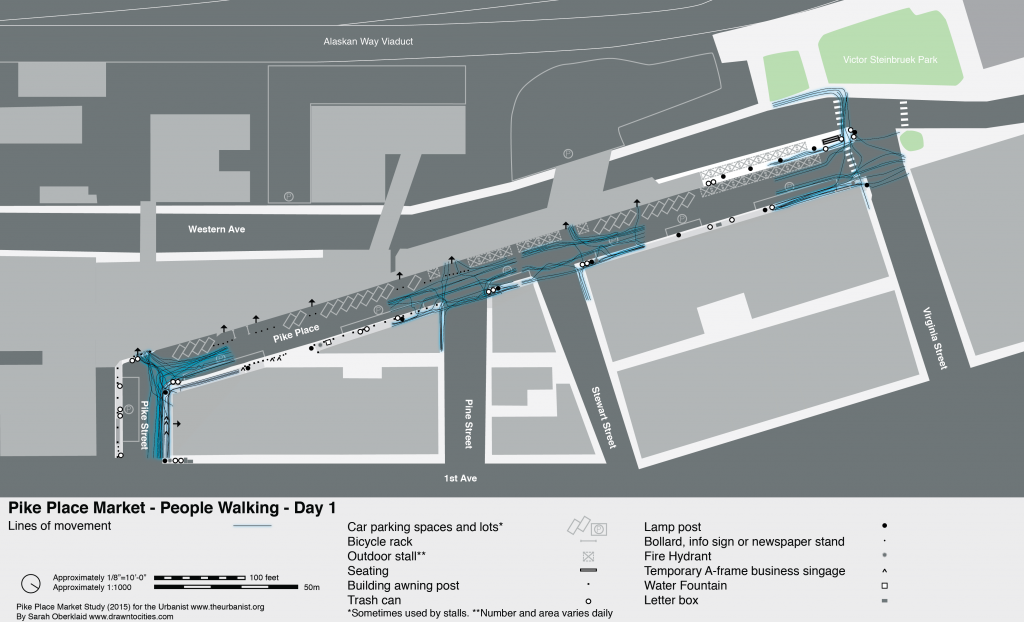

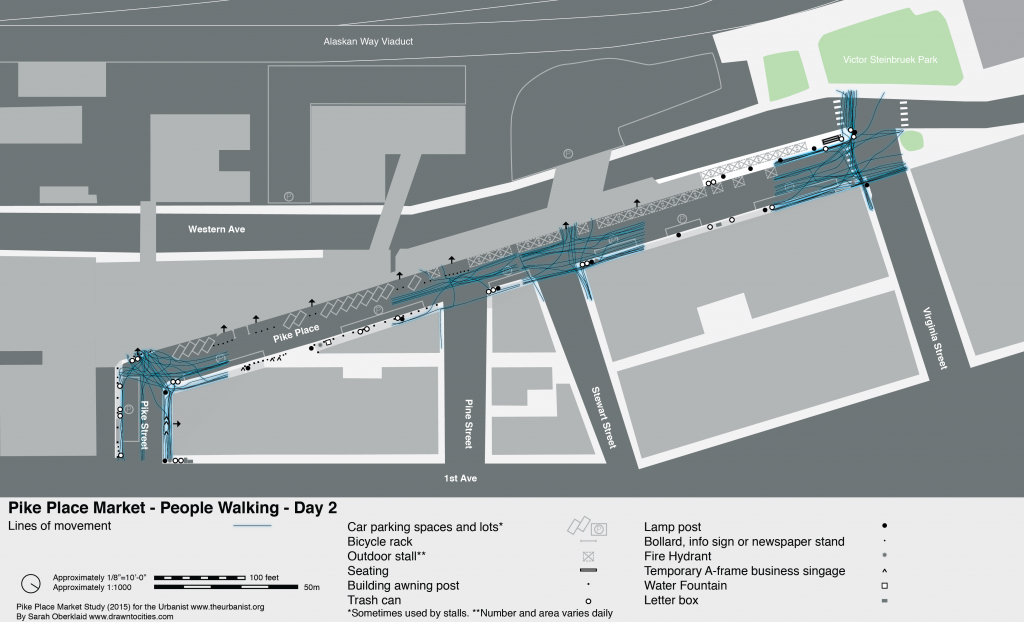

2.2 Tracing Pedestrian Movement: Where are people moving at Pike Place Market?

Tracing where people walk highlights movement patterns. It suggests where people prefer to walk, and the usage of infrastructure such as pavements, roads, crossings, and entrances to buildings. Movement studies can reveal impediments to people’s movement such as design (e.g. the presence or absence of lighting at night, or trash cans in the way of the sidewalk), environmental (e.g. areas in the sun, shade, or protected from the wind), and social factors (e.g. places with a presence of people sitting or standing around may influence perception of safety).

Approach

People’s movements were observed for 10 minutes at four different areas which provided a connection between a cross street and an entrance. An individual’s complete movement within the area was drawn onto a base map. Tracing is not exact and it is not possible to document everyone due to the high volume of pedestrians. To illustrate the variety of pedestrian flow, as many diverse movements as possible were captured by tracing one individual’s path and then selecting another person walking in a different direction.

Impressions

The pedestrian traces highlight that people don’t restrict their movements to the sidewalk, but freely walk in the road space and along or through the car parking spaces. These ubiquitous movements both impact and can be impacted by traffic. A theory could be that people walk along the sidewalks to observe the shops and stalls, and have separation from moving cars while they use the road space to have the freedom to walk faster when sidewalks are crowded, to move in larger groups or with a stroller, wheelchair or bike, or to access the stalls on the western side. As one of the few places in Seattle where pedestrians have greater command of the right-of-way, they may simply be choosing to walk in the road space because they can safely.

At the busy Pike Street corner many stay on the sidewalk, however, several people walk in the street or car parking spaces due to a crowd looking at the grocery produce or taking photos of the Market sign. Many cross the road diagonally between the corner and the main entrance. Around the corner, the stretch of sidewalk leading to Pine Street is the most cluttered with street furniture, which is difficult to walk through when crowded resulting in people also walking along the street or car parking spaces. Near Stewart Street, people are observed walking both on the sidewalk or in the street, with several people walking close to the stalls. Although the sidewalk is less cluttered near Virginia Street, people still walk in the street. People tend to use the crosswalks, but often select a slightly more direct path to where they are going. This end is a key entrance and exit point with people moving between Victor Steinbrueck Park, the Market, and Virginia Street.

These studies, open to your interpretation, show pedestrians perceive the public space in Pike Place fluidly, comfortably extending out from sidewalks where busy and making use of the street space for their convenience. It however, begins to show potential impediments to movement as well as heightened points of interaction with other people or cars which may warrant consideration. Part 2 explores this in more detail focusing on stationary activity in Pike Place. Stay tuned.

Sarah is an urban planner and artist from Melbourne Australia, currently living in Seattle. She has contributed to diverse long-term projects addressing housing, transportation, community facilities, heritage and public spaces with extensive consultation with communities and other stakeholders. Her articles for The Urbanist focus on her passion for the design of sustainable, inviting and inclusive places, drawing on her research and experiences around the world.