The biggest challenge is implementation, Durkan said, which has been very true for her administration.

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, also known as COP26 as the 26th iteration of this annual event, is underway in Glasgow, Scotland. Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan and Washington Governor Jay Inslee made the trip to attend. Unfortunately, back at home, Mayor Durkan’s climate plans don’t appear to be making much headway, especially in comparison to leading mayors like Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo and London Mayor Sadiq Khan.

Seattle’s climate emissions continue to creep up, and Mayor Durkan abandoned a pledge to implement road pricing (also known as congestion pricing) in her first term. She has yet to deliver a promised emissions-free zone, let alone lay out a plan to do so — The Urbanist‘s Ryan Packer had to use a public records request to get a peek at preliminary plans, but the exact location of the pedestrianized low-emission zone remains redacted and a mystery. Bus funding has also suffered under her watch, despite overwhelming support from voters.

Other cities have taken huge strides to redesign their streets to prioritize climate-friendly transportation and reduce deadly crashes via pedestrianized streets and districts, protected bike lanes, and dedicated bus lanes. Seattle’s progress on reprioritizing street space has sputtered under Mayor Durkan, with numerous street safety projects delayed, canceled, or watered down. Relatedly, traffic fatalities are trending up despite a City pledge to eliminate road deaths by 2030.

Meanwhile, in Paris, Mayor Hidalgo has taken the pandemic as an opportunity to accelerate implementation of her climate-friendly transportation plans, such as pedestrianized streets including a prominent thoroughfare along the Seine River. Hidalgo also added car-free zones near schools, lowered speed limits, and aggressively rolled out a connected network of protected bike lanes. Paris’ transformation has been hugely successful in decreasing reliance on cars and lowering pollution. Many mayors in Europe, Asia, and Latin America have pursued similar policies.

Both Hidalgo and Durkan are prominent members of C40 Cities, an organization of nearly 100 mayors collaborating to tackle climate issues underwritten by funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies and other prominent nonprofits. From 2016 to 2019, Hidalgo chaired the group, before turning over the position to Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti. Durkan serves on the C40 steering committee. In 2018, a one-million-dollar Bloomberg Philanthropies grant allowed the Durkan administration to study Downtown road pricing, but that initial study came and went and has not resulted in a policy proposal so far.

At a C40 event on November 2nd, Durkan laid out the case — which undergirds C40’s work — that cities and their mayors will lead the way in implementing policies to avert climate catastrophe.

“Mayors are the front line in their cities for everything from who picked up the garbage or didn’t,” Durkan said. “Policy at the national level and central government level — their biggest challenge is how to implement it? What does that mean? Boots on the ground? Our first thought is, how do you implement and what does it mean to real people?”

Mayor Durkan did roll out a new initiative on building emissions last week: “On Monday, I announced my newest Executive Order to accelerate action toward net zero emission buildings, healthy and equitable transportation, and clean energy workforce development to advance climate justice. Actions announced this week are projected to reduce the City’s building carbon emissions an additional 27% by 2050,” the Mayor said in a press release.

In Seattle, transportation is overwhelmingly the top source of climate emissions, accounting for two-thirds of the city’s carbon footprint. Mayor Durkan has periodically addressed the need for fewer cars and prioritizing alternatives in her speeches, but her actions haven’t necessarily matched. Promises to make her Stay Healthy streets program — which upgrades neighborhood greenways with signage diverting motorized through traffic — permanent and expand them into more areas haven’t yet been fleshed out, although her press release hinted at an expansion in the works. She has yet to fully commit to pedestrianization, safe bike infrastructure, and prioritizing transit in practice.

The same goes for Washington, D.C. where lawmakers announced an infrastructure package agreement in the midst of COP26 that will invest the lion’s share in highway expansion, following the same pattern of the last 70 years that created such a big climate problem in the first place. Plus, hopes of coupling the infrastructure bill to Biden’s climate plan now rest on a handshake agreement with waffling center-right Democrats (i.e., Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema). It hardly inspires confidence that the United States has turned a new leaf.

Still, American leaders reaffirmed climate commitments and pledged to do better in the future.

Inslee’s pledges

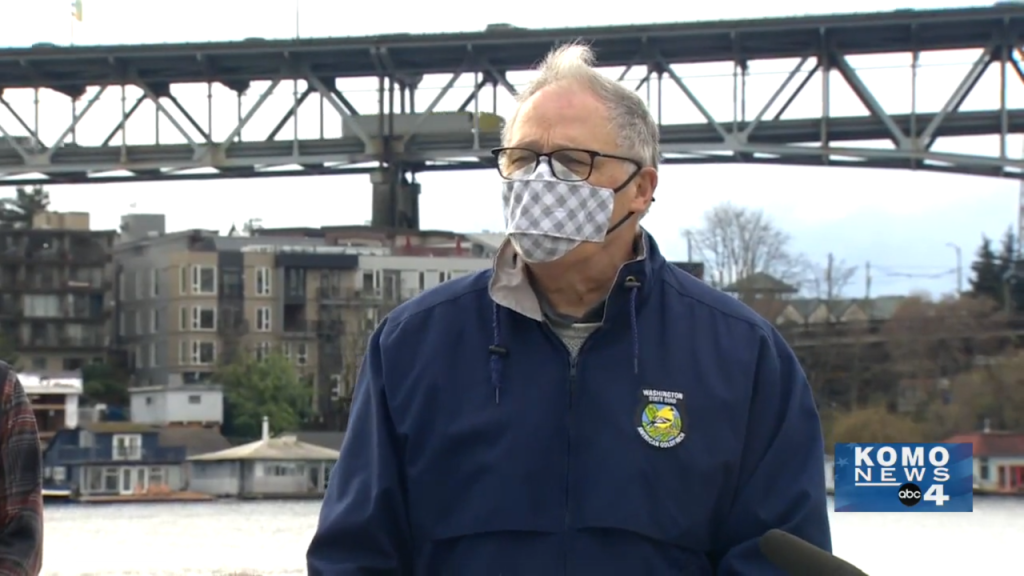

“Together with the rest of the leaders here and those everywhere else today who are committed to this fight, we will lead the charge on decarbonizing the transportation sector,” Inslee said in a statement on Sunday.

Governor Inslee also issued an executive order laying out a timeline to electrify the state’s fleet of automobiles.

“We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to effectively mitigate climate change. The actions we take in the next five years will determine the fate of our species. I’m proud to stand with this global coalition of governors and mayors to go beyond pledges,” Inslee said. “Together, we are charting a path to make tangible, meaningful progress to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030 and get to net-zero by 2050. Now is the time for leaders to buckle down and get it done.”

Among the Governor’s commitments are pledges to require 100% of new car sales be zero-emission vehicles beginning 2035 and 100% zero-carbon energy by 2045, as well as ensuring 100% net-zero operating emissions from new building construction from 2030. Other commitments include conserving at least 30% of land and coastal waters by 2030 and ensuring that at least 40% of expenditures benefit overburdened communities and vulnerable populations, the Governor’s office said.

Inslee’s press release noted “a recent United Nations report showed that with current emissions projections, the world should be prepared for a temperature rise of about 2.7°C by the end of the century. The consequences of this rise would be catastrophic, and again underline the need for short-term — as well as long term — commitments. Although today’s pledges are an important step, it is clear that more needs to be done at all levels to ensure genuine progress on climate change.”

Governor Inslee has yet to specify how the massive infusion of federal infrastructure funding would be spent in his state. Last year, Inslee stressed road maintenance but also highlighted the need for some highway widening projects, such as the I-5 Columbia Crossing bridge replacement connecting Washington to Oregon.

On the other hand, Governor Inslee did finally get major climate legislation passed in 2021 that will set up a cap-and-trade carbon pricing system in Washington State. The state legislature also passed a long-sought clean fuels standard, but had to write a promise to pass a transportation bill (which at the time remained focused on highway expansion under senate transportation chair Steve Hobbs’ leadership) into the bill to do it.

In the eyes of some climate leaders, this is two steps forward and one step back type of approach. If we keep designing a transportation system around wider highways and prioritizing cars, decarbonizing is going to remain out of reach.

Harrell steps in for Durkan

For her part, Mayor Durkan, after deciding against running for reelection, now hands the baton to her friend and ally in Mayor-Elect Bruce Harrell. Harrell brandished his climate credentials in his run, which included supporting Seattle’s Green New Deal legislation, which set the ambitious goal of carbon neutrality by 2030. Harrell’s platform cities Seattle’s older goal of carbon neutrality by 2050 and made a pledge to “make transit faster by expanding dedicated bus lanes.” While Harrell didn’t single out any specific bus routes, he did mention left-behind neighborhoods: “We need to make transit better than driving for more people and more neighborhoods — especially those that have been neglected for so long, such as in South Seattle.”

Making transit faster than driving could be a tall order considering Seattle has yet to build a true bus rapid transit line, settling for RapidRide brand that typically doesn’t meet the standard for speed and quality. Still, Mayor Harrell could show he’s serious by reviving and adding more transit priority to the RapidRide R Line upgrade to Route 7 that the Durkan administration shelved this year and bring back RapidRide plans for Route 48 that Durkan shelved in 2018.

Speeding up development of safe biking infrastructure might take a back seat for Harrell, however, given his campaign statements downplaying the priority and saying he “wouldn’t lead with bikes.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrianizing streets, blanketing the city in bus lanes, and unleashing a mass timber building spree to end the affordable housing shortage and avert our coming climate catastrophe. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in East Fremont and loves to explore the city on his bike.