When the Seattle City Council passed new rules on microhousing in 2014, opponents had hoped to put an end to the small apartments, while advocates warned that the Council would be killing off one of the few sources of affordable new construction. Over a year after the new rules came into effect, there’s now enough data to evaluate the impact of the changes. Unfortunately, the results will likely be disappointing to both sides.

For opponents of microhousing, the rules failed to reign in development: about the same number of projects entered the pipeline in 2015 as the year before the rule change. But just as affordability advocates warned, the new projects no longer include the lowest priced units.

Prior to the rule change, there were two types of microhousing. The most common form, typified by the aPodment brand, consisted of up to eight individually rented sleeping rooms around a shared kitchen. An even denser model called “congregate housing” placed no maximum on the number of sleeping rooms sharing a kitchen.

The compromise reached in 2014 did away with the first model entirely and replaced it with a new category called “small efficiency dwelling units”. These units would have to be a minimum of 220 square feet and include a kitchen in every unit, among other new regulations. Congregate housing remained mostly unchanged in form, but could now only be built in commercial zones, not lowrise residential zones as before.

To evaluate the effects of these changes, I compared an official City analysis of microhousing development from 2010-2013 with permit data from 2015. (I left 2014 out of the analysis completely, since the City study that I rely on for pre-rule change data only covers through June 2014.) The map below shows all of the new microhousing developments for which permit applications were made in 2015.

Interactive map of 2015 microhousing projects. Click on pins to see project information and renderings. (City of Seattle and Seattle In Progress)

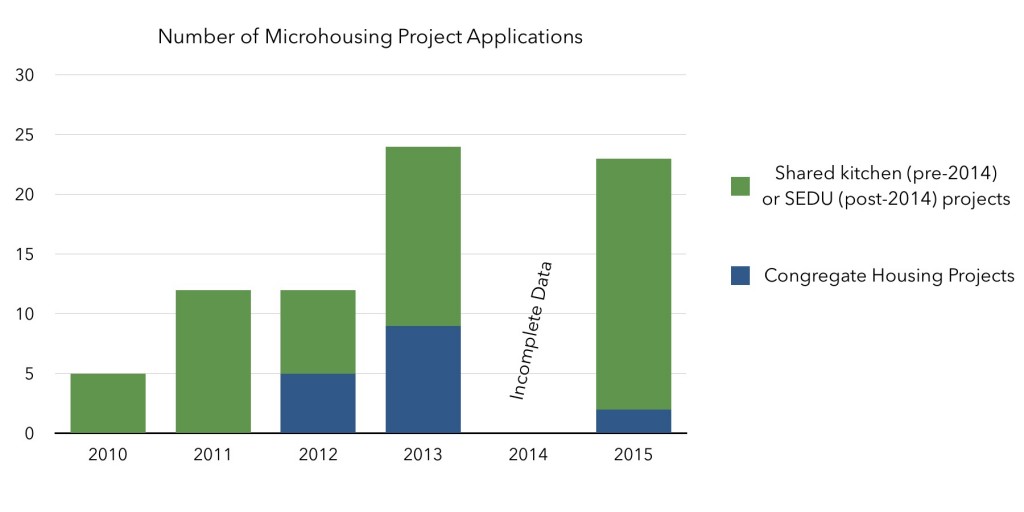

Perhaps surprisingly, the permit applications show only a minor dip after the new regulations. Applications held steady in 2011 and 2012 at exactly 12 projects per year, then doubled in 2013 to 24 applications. In 2015, Seattle saw 23 permit applications. The decline was slightly more noticeable in terms of total number of units: 2013 applications totaled 1,285 units, compared to 1,025 in 2015.

These numbers don’t mean that the regulations had no effect, however. Applications for congregate residences, the densest and most affordable form of microhousing, dropped off from 9 in 2013 to just 2 in 2015, due to restrictions on where they can be built.

Plus, the 900+ small efficiency dwelling units applied for in 2015 must conform to the new requirements of an in-unit kitchen and a minimum of 220 square feet. It’s too soon to know rental prices on these new projects. But an analysis of six microhousing projects built under the old rules showed that the smallest units, averaging 160 square feet, rented for $785 per month, while larger units, averaging 246 square feet, rented for $954 per month. Since the new rules require in-unit kitchens and a more extensive review process, it’s reasonable to believe that the cheapest units produced under the new rules could rent for $300 per month more than the cheapest units produced under the old rules.

I asked David Neiman, an architect and developer who has produced microhousing before and after the rule change, what he thought of the new rules. “Our energy has been directed into producing housing that is significantly larger, more expensive and less plentiful than before — the exact opposite direction from where we need to be going,” Neiman said.

The Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda currently before City Council includes a recommendation to re-visit the new microhousing rules. “The industry was building 1,000 units a year of affordable housing…with no public subsidy whatsoever,” Neiman says. “We could get back there in an instant with the stroke of a pen.”

Ethan is the founder and lead organizer for Seattle Tech 4 Housing, a grassroots education and advocacy group fighting for progressive housing reform. Seattle Tech 4 Housing was founded on the principals that the tech boom can and should benefit every Seattle resident; that abundant and affordable housing is the foundation of an equitable city; and that the tech community in particular has a responsibility to fight for solutions. Ethan is also the founder of Seattle in Progress, a real estate tech consultancy and website for tracking construction in Seattle.