The process for Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) rezones in Downtown and South Lake Union kicked off last week with a briefing before Seattle’s Planning, Land Use, and Zoning Committee. The rezones would increase overall development capacity in many Downtown and South Lake Union zones by bumping up maximum building height and floor area allowances. Benefits of the rezone could include 21,000 new market-rate homes, 53,000 new jobs, thousands for rent-restricted, income-restricted affordable housing units, and millions of dollars of investment in voluntary public amenities.

Lots of Affordable Housing

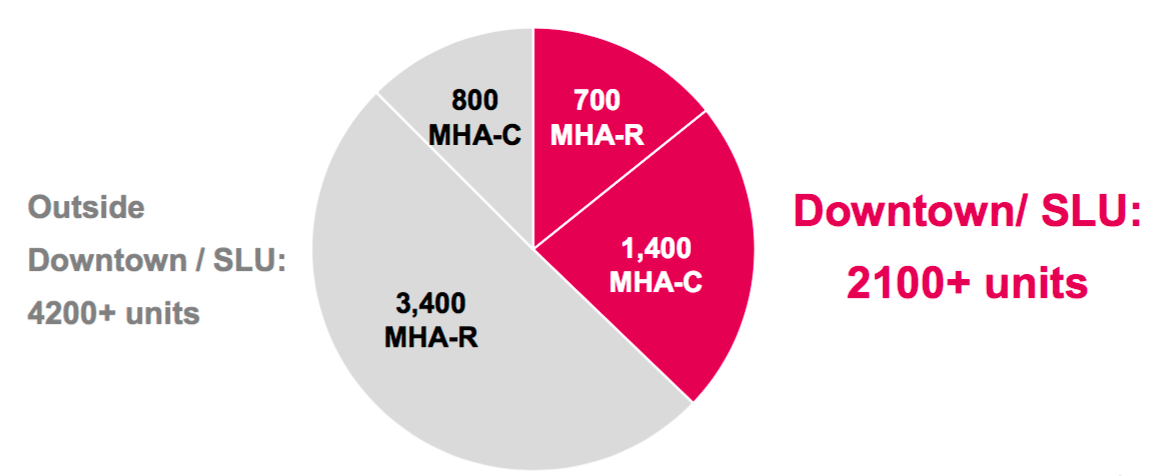

The Downtown and South Lake Union rezones would deliver a lot of affordable housing. About a third of the affordable housing units created through the city-wide MHA program would be brought to market from developments in Downtown and South Lake Union over the next ten years. The Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) estimates more than 6,000 rent-restricted, income-restricted affordable housing units will be delivered over that period of time with 2,100 affordable housing units coming from Downtown and South Lake Union. The OPCD breaks down that estimate and assumes that about 700 affordable housing units will be derived from residential development while another 1,400 affordable housing units will come from commercial development in Downtown and South Lake Union.

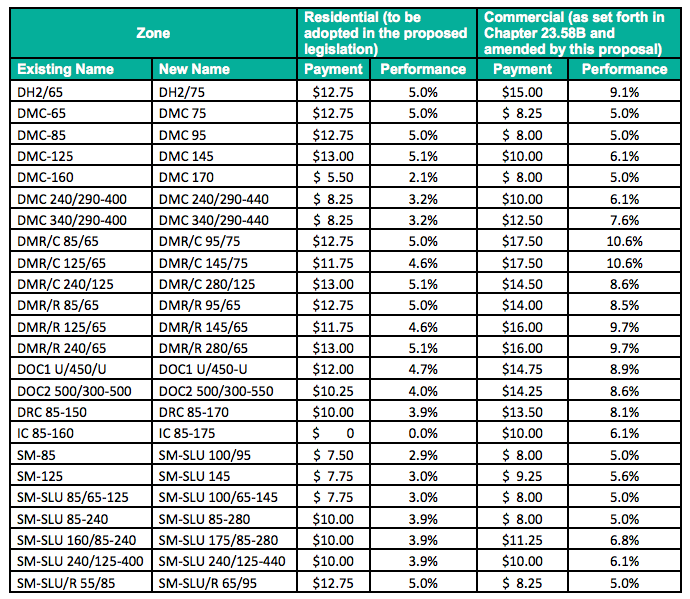

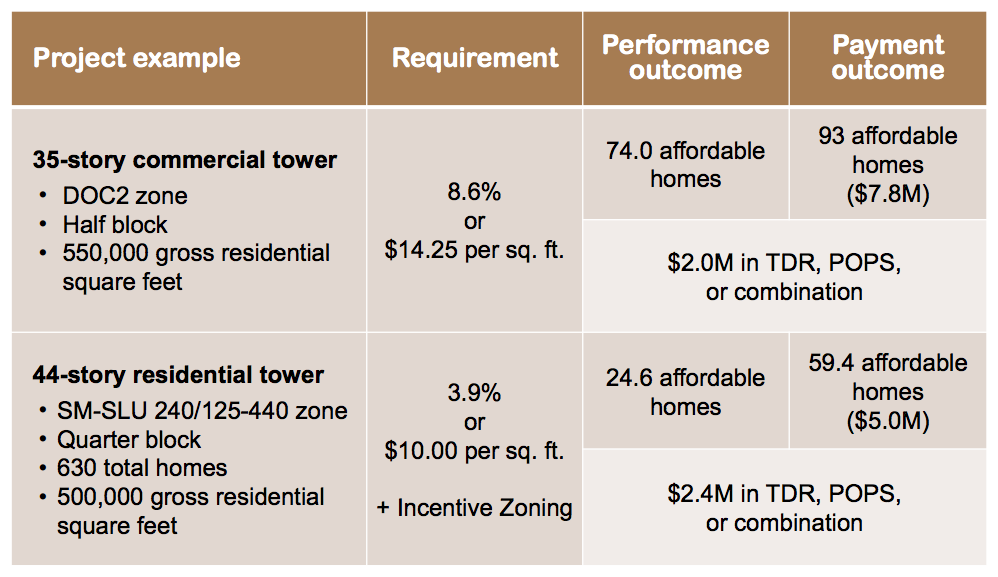

To ensure that all of this affordable housing is built, the rezones will require developers to either construct affordable housing or pay a fee to the City to develop affordable housing instead. The amounts required vary greatly by use and zone. On the low end, a brand new residential tower development in the proposed DMC-170 zone would only be required to provide 2.1% of the total units as affordable housing; alternatively, the developer could pay a fee equal to $5.50 per square foot. On the high end, a brand new commercial tower development in the proposed DMR/C 95/75 zone would be required to provide affordable housing equal to 10.6% of the total commercial square footage or $17.50 per square foot.

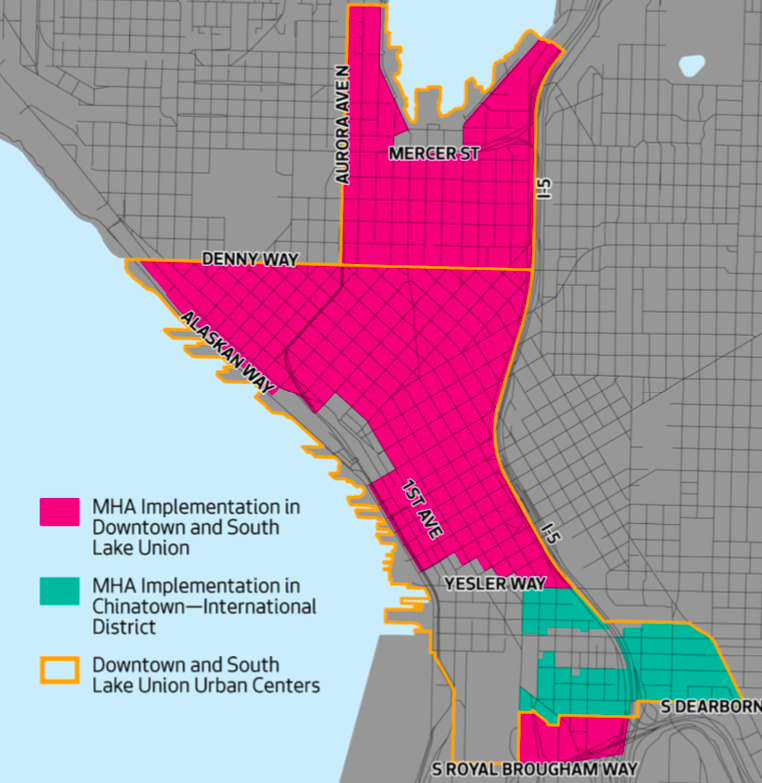

Large Swaths to Be Rezone

Most areas of Downtown and South Lake Union will be rezoned. A handful of areas won’t be rezoned as part of the legislation. These include the historic districts in Pioneer Square and Pike Place Market, historic waterfront piers, Pike Place Market view corridor, South Lake Union lakefront, and Chinatown-International District. The latter (Chinatown-International District) will move forward through separate legislation to be taken up by the City Council later. The rezones won’t just be naming changes on a map. The underlying development code will also be modified to increase allowed building heights and floor area allowances.

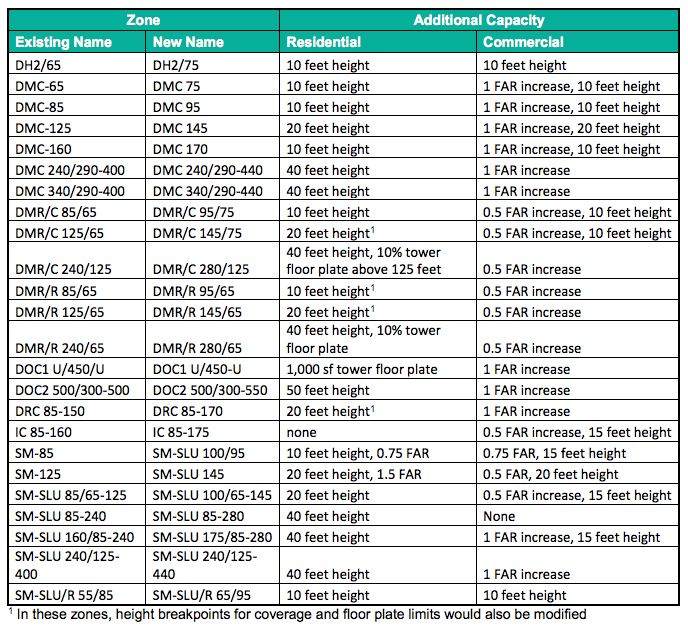

The zoning changes will be very different from zone to zone. Generally, the zoning changes will increase the maximum floor area ratio (FAR) by 0.5 to 1.0 FAR for non-residential towers while residential towers will be allowed additional height. OPCD has a prepared a more precise table indicating the development capacity changes proposed in the legislation:

For a deeper dive on the proposed rezones, see our previous detailed analysis on the topic.

Retaining Incentives

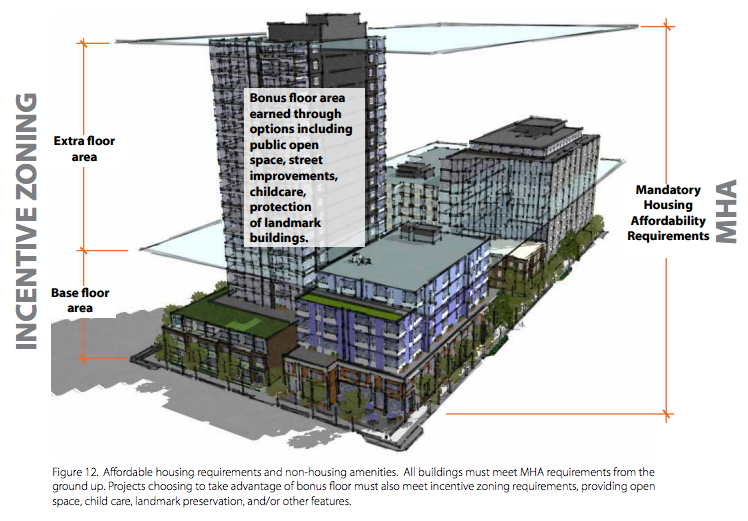

Incentive zoning has been on the books for a long time in many Downtown and South Lake Union zones. Various options to buy additional height and floor area have been added over time to include development of things like child care facilities, green streets, hillclimb assists, and public plazas and atriums, and encourage purchase of transfer of development rights (TDR) to protect historic structures and farmland. These incentives have delivered many important public benefits over the years. The legislation would retain them in their current form, which would require developers to use incentive options for any development above the base maximum height and floor area allowances otherwise permitted.

These incentives requirements would be in addition the MHA requirements, which apply to all portions of a structure. Because of the delicate interplay of MHA requirements and other incentives, however, the general MHA requirements would be lower than they might otherwise be if the other incentive requirements weren’t going to be kept. This makes sense considering that the existing incentives would generally apply to the added height and floor area permitted by the rezones.

To provide a few examples of this interplay, OPCD has prepared theoretical models:

In total, OPCD estimates that the incentives would help deliver the equivalent of $90 million worth of green street, open space, and TDR investments over the next 20 years.

Fewer Tower Races

Some proposals for tower developments have been a race to the finish, leaving some developers on the losing end. That’s because the City’s development code generally requires tower separation. Often only one tower is allowed per block face and in some areas other tower separation requirements may apply. When a new tower is proposed, it isn’t considered an “existing tower” until a Master Use Permit decision has been issued. That means a tower proposal would have had to have waded through the whole design review, environmental review, and land use review process before being considered an “existing tower.” Multiple design review meetings, appeals, long zoning reviews, and processing of multiple versions of plan sets by consultants could severely delay one proposal while another similar or lesser project could sail through the process. That poses a serious challenge when two new tower proposals seek to locate nearby each other pitting them against one another to get through the process fastest to win land use approval and “existing tower” status.

The proposed legislation should reduce the number of these warring tower races by granting “existing tower” status much sooner in the process. Generally, a proposed tower project could gain the status if a complete application for Early Design Guidance (design review) has been filed with the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections. The policy change would in effect give upfront certainty to developers who want to go tall and saving them the financial headache of coming out on the losing side of a tower race.

Allowing Modifications

Finally, the proposed legislation would carve out new modification provisions related to the MHA requirements. Recognizing that there may be limited instances where development proposals might not be able to use additional development capacity to be provided by the MHA rezones, the proposed modification provisions would outline how a developer could qualify for adjustments to development regulations and MHA requirements. Using a two-step process, OPCD says that proposed modification provisions should address this issue as follows:

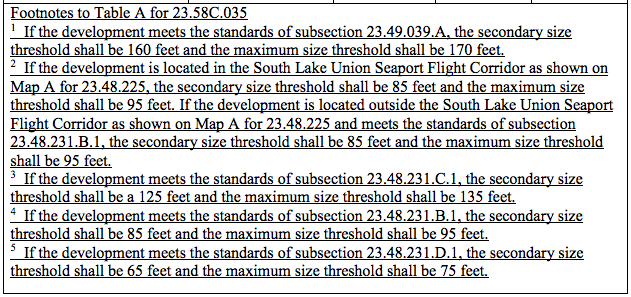

First, the proposal includes provisions for certain zones under which, if certain identified development standards would prevent a development from achieving certain measures of capacity (for example, a certain height), other development standards would be modified (for example, allowing slightly wider towers). OPCD expects that these provisions would ensure the additional residential development capacity could be achieved in virtually every case.

Second, to address a scenario where the additional capacity could still not be achieved, the proposal includes a provision by which payment and performance amounts under the MHA-R program would be modestly reduced if a development could not achieve certain size thresholds.

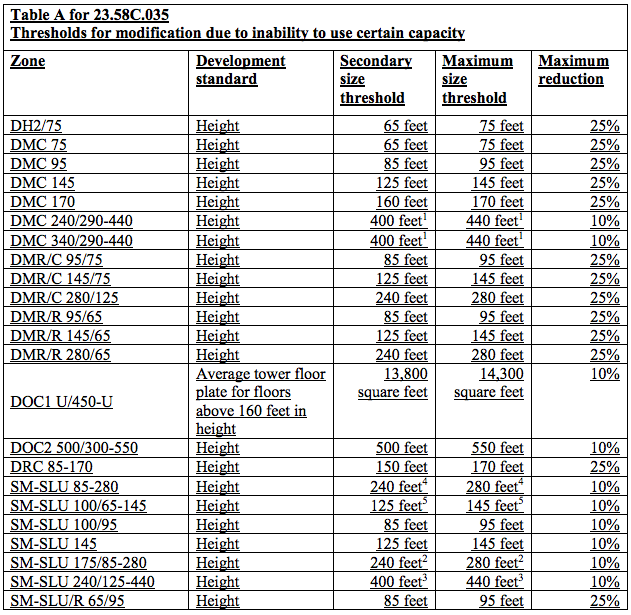

The development code would see a variety of different provisions added to the chapters related to Downtown and South Lake Union to provide alternative development standards so that development proposals would still be able to achieve increased development and remain subject to the standard MHA requirements. In the event that it is determined that those provisions still do not provide sufficient relief, a direct modification to the MHA requirements could be permitted. The maximum reduction that would be allowed differs by zone, ranging from 10% to 25% of the standard MHA requirements otherwise applicable.

The PLUZ Committee will discuss this legislation further in March. A public hearing is planned for the evening of March 13th where the public will be invited to speak on the bill, meaning that there will be at least one additional committee meeting on the legislation afterward–though likely more.

Related Articles

A First Look At The Downtown And South Lake Union MHA Rezones

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.