On Black Friday, a motorist attempting a turn from Aurora Avenue to N 39th St careened over the curb and plowed into a family walking on the sidewalk. The daughter died on the spot and her older brother later at the hospital. The two lives snuffed out far too early bring the death count of this treacherous six-mile North Seattle stretch of Aurora Avenue to six in 2019 alone–citywide 15 people have died while walking or biking this year. Overall, pedestrian injuries and deaths are on the rise both nationwide, statewide, and here in Seattle.

Some chalk it up as stuff happens, but let’s sit with this tragedy for a second. It’s something many of us have done. With relatives in town over the holidays, we take them sightseeing–in this case to the Fremont Troll. But while walking down the sidewalk, some motorist does something reckless on a road designed for speed, and now the parents that came to visit their daughter and her boyfriend with their son have their family torn apart.

Imagine being that parent who raised two kids to young adulthood, nurturing them and supporting their talents, and suddenly they’re lying dead on the pavement. Bright futures are snuffed out, and you’re left with lacerated ribs that will likely heal but a broken heart that may not.

These aren’t just statistics we’re worried about, but the human tragedy behind every one of those statistics. The escalating human tragedy underscores the need to redesign Aurora Avenue immediately. The details of a comprehensive plan can still be hashed out, but it must contain three key elements:

- Lower speeds via lower posted limits, narrower car lanes, and design cues.

- A robust sidewalk network by adding sidewalks where they’re lacking, widening them where they’re too narrow, and adding bollards at dangerous intersections like N 39th St.

- Complete bus lanes to calm traffic on the curb lane and carry more people on safe buses rather than dangerous personal vehicles.

Perhaps the driver was particularly inattentive–she was high on meth, reportedly. Moreover, after strangers helped her pry her free, she fled her wrecked car and the bodies she had mangled. Luckily, a good Samaritan hopped off a King County Metro bus and tracked the women to some bushes to keep a watchful eye until police arrived. An impaired driver perpetrating a hit-and-run makes an easy scapegoat and a way to avoid a larger conversation around safety.

However, the high rate of crashes and deaths on Aurora Avenue shows she is hardly alone. Safe streets advocates aren’t letting the City off the hook. Anna Zivarts, executive director of Rooted in Rights, penned a brilliant op-ed calling for us to fundamentally redesign our streets to put safety first rather than speed and car-moving efficiency. Likewise, Seattle Greenways has called for lower speed limits and safer street designs. We echo their calls. And if we can fix Aurora Avenue, we can fix every street in Seattle.

Lower Speed Limits to Save Lives

We should lower speed limits to decrease the likelihood of deaths and serious injuries. Luckily, Mayor Jenny Durkan announced a plan to lower speed limits on arterials on Tuesday. Unfortunately, Aurora Avenue isn’t a part of that plan until the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) and the Washington Department of Transportation (WSDOT), which shares management of the road, come together and both sign off. Moreover, SDOT has announced a timeline wherein the real planning work for the future of Aurora Avenue won’t even start until 2021. How many more people will die by then?

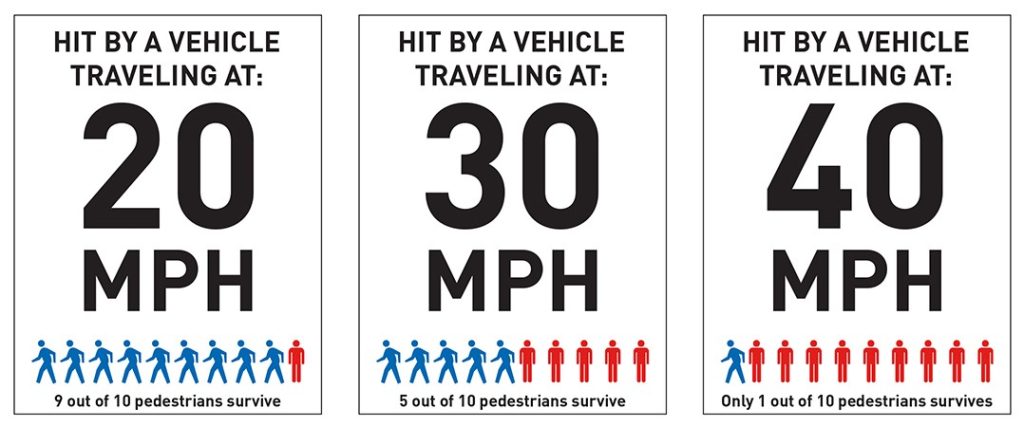

Speed really does kill when it comes to car crashes. When a motorist traveling at a speed of 40 miles per hour (equivalent to 65 kilometers per hour) hits a pedestrian, that person dies 90% of the time. However, if that car is traveling 20 mph, that person survives 90% of the time. Reaction times also improve so that drivers have time to slam on the brakes. Even slowing a car from 30 mph to 25 mph doubles the chance a pedestrian survives a collision with said car.

The posted speed limit on Aurora Avenue is 40 mph, but speeding is rampant. 50 mph is routine and 60 mph isn’t uncommon when the road isn’t jammed up. Lowering Aurora Avenue’s speed limit to 25 mph (or even 30 mph if that’s too dramatic) would send a message that SDOT and WSDOT are serious about safety on the deadliest road of 2019.

We shouldn’t just lower speed limits, but redesign the street to match, changing the design cues that subconsciously encourage a motorist to speed. One big culprit is wide lanes. Give motorists wide berth and they step on the gas feeling comfortable. A narrower lane sends the opposite cue to be alert and slow down since staying within the margins isn’t so easy.

More Sidewalks

The sidewalks on Aurora are pathetic and that needs to change. Many places they must be widened and some places, particularly in the north, lack them entirely. We need connected sidewalks throughout. The most crash-prone intersections should have heavy-duty bollards so that an out-of-control motorist cannot jump the curb like the one fatally did on Black Friday.

Extend the Bus Lanes

Bus lanes serve three major purposes. Firstly, it obviously makes transit better. Cities that add bus lanes have seen transit times shrunk–by more than 20%. The RapidRide E Line is the region’s busiest bus with 18,000 daily riders, but it’s still bogged down in traffic far too often. Much of the route lacks bus lanes.

Secondly, bus lanes further reinforces design cues to slow down. Painting bus lanes on the outside lanes could further shrink the perceived land width and give motorists the cue that they should be careful when making right turns as permitted via those business access and transit (BAT) lanes. Some research has found bus lanes also lead to fewer collisions, too. For example, San Francisco saw 16% fewer collisions on streets where it rolled out bus lanes.

Thirdly, faster, more reliable bus routes will attract more riders and put more people in the safety of a bus driven by a professional rather than an amateur road warrior in a dangerous sports utility vehicle paying half-attention and meeting only woefully low standards for driver competence.

A New Aurora

We’ve written a lot about Aurora Avenue on this site–including a piece earlier today. We agree with the arguments brought forth; Aurora Avenue has too much potential to squander. Similarly, people getting around Seattle have too much potential. Let’s not treat them as disposable and let them die on our roads without doing something about it.

The three interventions we’ve outlined would change the equation, subtracting some unhealthy car dependence for safety, walkability, and more transit reliability. Taming the street would allow a more inclusive neighborhood grow around it where kids, seniors, and disabled people can feel comfortable and safe. We’d rather live in that world rather than the one we live in now–a world where cars rule supreme and parents cradle their dead children on the side of the road.

The Editorial Board is composed of Natalie Bicknell, Ryan Packer, and Doug Trumm.

The Urbanist was founded in 2014 to examine and influence urban policies. We believe cities provide unique opportunities for addressing many of the most challenging social, environmental, and economic problems. We serve as a resource for promoting and disseminating ideas, creating community, increasing political participation, and improving the places we live.