This week’s financial news has been grim. With markets getting fleeced by the spreading impacts of COVID-19 and a weak response from federal officials, the likelihood of a recession is looming. Locally, the major employers around Seattle are having their staff work from home, impacting everyone from baristas to Lyft drivers to dog walkers who are seeing their hours cut to nothing. Movements are forming to support these workers.

In times of economic downturn, federal and state governments have a choice. They can go hard into austerity measures that cut future productivity and harshly impact people’s lives. Or they can take advantage of lower borrowing costs and available labor to build projects that improve the community, keep people working, and set the stage for a more livable city.

It would be irresponsible to live in denial that the economy will continue to expand forever. Whether or not this week marks the beginning of a recession we can start formulating a HoneyDo list for our governments. It’s not to just ride out an economic downturn, but to correct long standing needs that will improve our community. Here are some ideas.

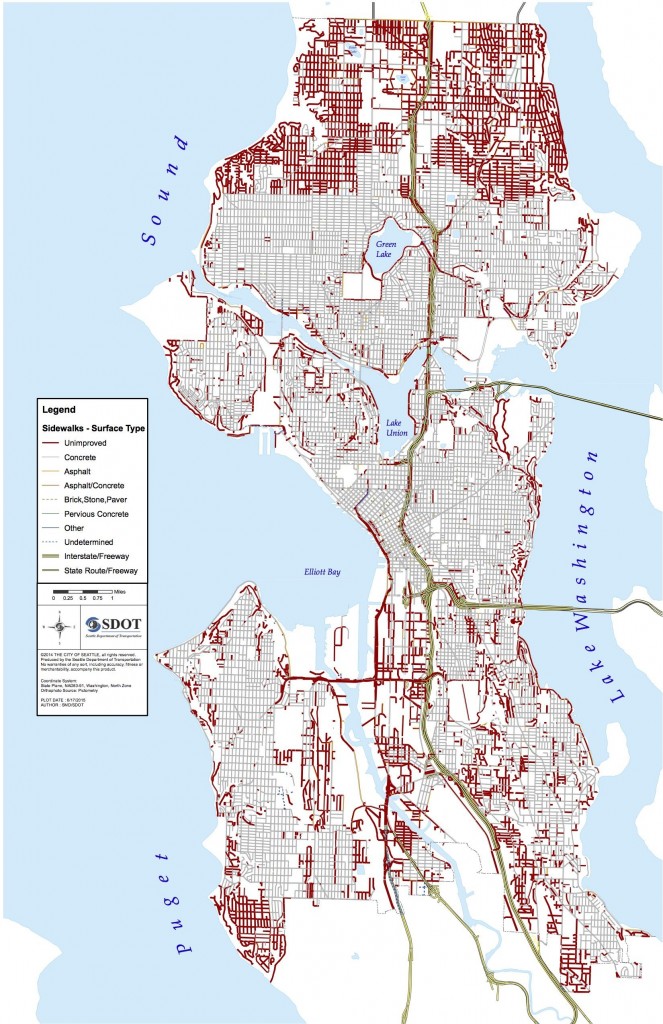

Sidewalks

Though Seattle annexed portions of Arbor Heights and North Park as far back as 1907 with the promise of adding sidewalks, the city is still about 11,000 blocks (or 26%) short of a complete network. The budget under various levies only corrects that by about 25 blocks per year.

The stated cost of full curb and gutter on all sidewalks at SDOT’s estimate of $350,000 per block would be about $4 billion total. This is approximately two-thirds of Seattle’s annual budget. (However, it is about eight years worth of WSDOT’s highway maintenance budget, and sidewalks are a much better use of that money.)

But, with the cratering bond market, municipal bonds have dropped from 3% annual interest to less than 2%–that’s below the inflation rate making the real costs of borrowing effectively zero and potentially negative. For a thirty year bond on $4 billion dollars, that is a difference between paying $228 million per year and $198 million per year. Or 3.8% of the budget versus 3.3%. It is a lot of money, but it’s an excellent example of how taking advantage of these interest rates allow us to finish a project that’s been put off for 113 years.

Underground power lines

Though we live in an active fault zone that can see high winds and storms, only a quarter of Seattle’s power lines are underground. Part of this is the expense, with few neighborhoods taking on the improvement districts to tax themselves for the improvement. Most estimates put burying power lines at $1 million per mile. It’s often more expensive than that, since we are not a greenfield development and multiple lines will need to avoid varied obstructions on any given block.

The opportunity here would be that many of the roads that need sidewalks also need to have their utilities buried. Two birds with one pour of concrete or brick pavers.

Our overhead wires are not just ugly, vulnerable, and dangerous in an emergency. They are also an impediment to better street trees. Mature trees are regularly butchered or removed to protect overhead wires. Street trees can improve the conditions near the heat-island causing asphalt. And with 3,500 miles of roads in the city, lining them with trees will get us closer to the 30% tree coverage goal than a tree ordinance that could be easily manipulated to stall and harass new housing.

Continue to expand transit

Buses and the people who drive and repair them are expensive, as are continuing to expand light rail and pursue high speed rail. We must continue to fund all of it.

The first benefit of continuing transit is that we continue to employ thousands of well-paid professional drivers and mechanics who are part of our community. We don’t need to shoot ourselves in the foot trying to save a few bucks. And if we take good bus operators away, it’ll be harder to get around with a hole in our foot anyway.

Second, let’s boost transit capacity so the system will be better as need returns. We’re going to have the sidewalks being built and wires buried, let’s paint the streets with bus lanes and add new and upgraded bus shelters while we’re at it. These are relatively inexpensive improvements that can be undertaken community-by-community.

Slightly larger, we must continue to develop high capacity and high speed transit. This is literally the best time to borrow the money to complete large projects. Hundreds of construction and engineering employees are at work on these projects. We still have a responsibility to work toward reductions in traffic and emissions. There’s also history, like the Shinkansen coming from Japanese post-war reconstruction and the TGV development during France’s long recession in the 1970’s.

On the flip side, there are going to be arguments against continuing big projects. They’re expensive, long-term, and suck money that can go to cutting taxes. But bad public policy comes from capitulating to sob stories about waning corporate profitability. We must clearly state that our hard-won light rail and high speed future are not negotiable.

Finally, improving transit capacity allows it to remain ubiquitous. There will be people changing jobs in any recession. Getting reliably to new workplaces is vital. Doing so dependably is compassionate. Connecting to a new job should be the lowest concern for people returning to work.

Honestly, this would be a good time to make transit free. We have experimented with sixty years of free highways and all it has done is spread people out and kill a lot of folks on the road every year. When loud special interests start making noise that minimum wage or local taxes are too high–as they inevitably will–we can point out that logic dictates transit should be free first. Reducing that literal out-of-pocket cost for most neighbors will mean real improvement in their lives. Vastly more than ephemeral property tax savings.

Home Improvement Bank

The city and county’s ability to borrow money at historically low levels can be used to improve the buildings along the sidewalks too. A revolving loan program seeded by the city can provide building owners low interest loans to make improvements. The city can use this to target long standing goals like reinforcing masonry or improving energy efficiency.

During good economic times, it is very easy to overlook the danger of unreinforced masonry in a seismic zone or the amount of wasted energy that is pouring out old windows. Seattle has over 1100 masonry buildings that could sustain dangerous damage in an earthquake. Large swaths of the city are covered by buildings constructed in the 1910’s and 1920’s, with the suspect insulation and antiquated systems that go along with them. Fully a quarter of the city is still heated by oil.

As pointed out in the City’s Unreinforced Masonry Program policy documents, the cost of seismic retrofits are rarely recouped. Energy efficiency does not fare much better in times of low gas prices and weak federal policy. In many ways, fixing brick and windows are the epitome of shovel-ready projects because they are just sitting there waiting for funds.

And the benefit goes further than just helping homeowners and landlords. Not every construction contractor can take on public infrastructure projects. While building sidewalks and rail can help larger firms hire staff, many smaller projects like windows and doors will help smaller firms stay robust and keep employees.

Open the libraries and community centers

We have talked about shovel-ready projects in terms of constructing physical infrastructure. But we can also talk about it in terms of not demolishing progress. After all, why spend the effort to tear something down when you’re going to need to build it again later.

When recessions hit municipal budgets, the first thing that is on the chopping block is often the basic services of libraries and community centers. Certain parts of the political spectrum will lecture about political realities and how much of a luxury it is to have a place to play basketball or read a free book. Such a mindset threatens to demolish another kind of infrastructure.

In his book Palaces for the People, Eric Klienenberg details how community gathering places are the real infrastructure that create healthy and vibrant neighborhoods. These are the social infrastructure–physical places where social capital develops. “When people engage in sustained, recurrent interaction, particularly while doing things that they enjoy, relationships inevitably grow.”

These relationships don’t just make folks happier. They save lives. Klienenberg details the event that got him researching the topic: a deadly 1995 heatwave in Chicago. Neighborhoods with safe, healthy, common places saw a fraction of the deaths that occurred in neighborhoods without that social infrastructure. Churches, barbershops, and block clubs functioned to help people check on their neighbors and fight the isolation that kills so many people in slow-moving catastrophes.

Neighborhoods with safe, healthy, common places saw a fraction of the deaths that occurred in neighborhoods without that social infrastructure. Churches, barbershops, and block clubs functioned to help people check on their neighbors and fight the isolation that kills so many people in slow moving catastrophes. Just like we must keep our bus drivers on the road and our homebuilders working, we must keep our gathering places open in a recession.

It seems strange to talk about places of social interaction as a remedy to the recession caused by COVID-19. We here in Hygge central will survive by pulling up to Netflix and detaching from the community for a while. However, you are unlikely to attend a community event with your neighbor one day, then beat them mercilessly for toilet paper the next. Even if that community event was DIY hand sanitizer party.

The worst effect of the slash-everything mentality that pervades cities during recessions is the perception of a zero sum game that turns our community against itself: Cut your services so I don’t lose mine. But improving sidewalks around Haller Lake does not take library funds from Roosevelt if we think ahead and prepare for what’s coming. Think how much cheaper it would have been if you bought the big bottle of hand sanitizer two weeks ago.

That is why we need projects in the pipeline. Projects that require staff and preparation will round out many sharp edges of economic trouble. Preparing a lot will let us see that overlap between sidewalks and buried power lines. We can replicate, repeat, and get good doing many things, quickly. Shovel ready is not having a weapon to use against our neighbor. It’s being there as neighbors ready to make our community stronger.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.