Issues Over Image (with Pictures)

Over this series of articles, I am laying out an argument that Seattle should mix industrial uses in our residential and commercial neighborhoods. A long history of exclusion keeps interesting and useful things out of our communities, an absolute loss for building a vibrant and vital city. Now is the time to change this because the lines have disappeared between the places we work, create, build, and live. Right now, every neighborhood is mixed use.

Read part one of the series introducing the concept of neighborhood industrial use. Read part two of the series going over the historic failures of zoning. Read part three of the series showing the contemporary issues in the convoluted zoning use table.

Over the last two weeks, we’ve seen the way zoning prevents good development. The ordinance creates groups of disfavored uses, defined broadly and outright banned. Use tables carve out exceptions that are so narrow as to only impact a single building. Zones are whittled down to specific lot lines that force design decisions to buffer with neighboring restrictive uses.

While zoning and its exceptions have been used to squeeze diverse uses into small clusters, there are some tools that make the zoning code function more fairly. These mechanisms depart from the bright-line rules of zoning, using expert input and common sense to make the code useful. More importantly, they give us a road map to building better neighborhoods.

Management Plans – The zoning ordinance is incomplete. Though it occasionally tries, it cannot define every use and creative way humans find to live. The ordinance already relies on support from city, county, state, and federal agencies to define and monitor it. From hiding non-residential requirements in the building code to piggy backing on permits from other departments, zoning already depends on inspection, testing, and verification to perform its primary functions.

Every non-residential use in a single-family residential zone requires a conditional use permit. The Director or Council “may mitigate adverse negative impacts by imposing requirements or conditions deemed necessary for the protection of other properties in the zone or vicinity in which the property is located.” This is the same language as industrial zones requiring management plans for high-intensity uses. We have the apparatus in place to compel inspections and continued monitoring of uses.

More importantly, we count what we care about. If we do not have reliable data about industrial uses because we simply shove them in a corner, it says a lot about where industry falls on our priorities list. The ordinance will be vastly improved by unifying and strengthening requirements for inspections and monitoring. The city should be able to track the real time noise, odors, vibration, and pollution. Not only will it allow us to respond quickly to emergencies, it also takes away a lot of stigma. We need real data to see if the mythical adverse impacts of commercial and industrial uses actually exist.

Averages – Not every parcel is equal. Some are truly weird shapes. So the ordinance utilizes averages to smooth out variations and allow construction on tiny or strange lots. The code looks at the whole block for locally applicable compromises. If an existing lot is too small for the normal setbacks and lot requirements, it is still buildable if it has 75% the area and 80% the average width of the block. We average front yards to determine setbacks. We average the size of ground floor retail in the Pike/Pine Commercial District. We average the area of upper residential floors in South Lake Union. Where a bright-line rule would impair the development among varied parcels, averages are used to apply the intent of the law without harsh restrictions.

Block averages should apply in irregularly shaped zones. Being a political process, the designation of zones is subject to forces that push and pull the boundaries into peculiar shapes. This is most egregious where blocks are split between restrictive residential uses and more flexible commercial uses. If a development crosses these lines, non-residential uses must stay in their own zones, emphasizing stark differences between the zones.

Split Block Averaging would consider the block as a whole and calculate the allowable residential and non-residential portions based on that. That ratio would then be allowed on all individual lots within that block. For the block at the corner of Queen Anne Ave and Galer St, all the lots on the main roads are zoned commercial and the rest residential giving a 60% commercial ratio for the whole block. Every lot on the block should be able to go 60/40 commercial/residential. Do the residential zones need to add commercial or vice versa? No, but the flexibility is there, creating a larger and stronger buffer with the completely residential zoning north and west.

Chaperone Uses – We already allow industrial and commercial uses in every residential zone. But they must be part of another use that we find favor with. Every school has a commercial kitchen and loading docks. Every community center has exercise classes, outdoor lights, and continual traffic. Homes are allowed to have workshops and full gymnasiums. We are fine with these uses when they come wrapped in a favored package.

A chaperone use is that favored package. Originally advocated by Al Zelinka and Dean Brennan in their book SafeScape: Creating Safer, More Livable Communities, chaperone uses started as police and fire stations placed near gun shops and strip clubs to mitigate crime. (We can discuss the ridiculousness of zoning and adult uses later.) Thinking more creatively, a chaperone use would be a permitted desirable neighborhood establishment with a secondary industrial use that would otherwise not be permitted.

Of course, here is where we have a big disclaimer to say that this is not about putting a gift shop on the front of a fish packing plant and dropping it in Laurelhurst. This is about a chaperone use that connects to the neighborhood as a window to allay objections to the secondary use. Chaperone uses make the secondary use visible, minimize objectionable impacts like vibration or noise, and integrate the whole operation into the community.

What Neighborhood Industrial looks like

Back to the thought about a fish packing plant in Laurelhurst for a second. That it even needs to be said that fish packing is not an acceptable industry for residential areas shows how broken our discussion of industrial uses has become. That we have defined “industry” so broadly as to encompass everything from chocolate making through uranium factories gives us a perspective on why it’s important to break down these distinctions and address the issues, not the image.

Neighborhood industrial looks like the stuff we’re doing in our homes, from cooking and exercise through work and hobbies. The change is that we are allowed to make space for those activities to be larger and become a part of the community. That can happen in a building like this:

The ground level taproom is the chaperone use, and it shares front wall space with access to the residential areas. Behind the taproom, the building can accommodate a much higher ceiling for the actual brewery. The recessed foundation floor allows the brewery equipment to sit on solid ground and have extra height. Shared community space above the brewing area further shields residences from noise.

A steel mill will not fit in this building. But a couple of very specific types of neighborhood industry can. Good design combined with management plans, split block averaging, and chaperone uses can allow our neighborhoods to reflect the varied and vibrant uses that are locked into our homes. These spaces can fit four types of industry:

Back-of-storefront manufacturing

We may not think of a candy kitchen or an artisan soap shop as manufacturing. However, once they automate part of their process–a taffy puller, a wrapping machine–the zoning ordinance kicks these businesses into lite manufacturing and industrial zoning. Any negative impacts of small manufacturing can be easily mitigated by a chaperone use and a management plan. The front of the house chaperone use–the candy store, the smelly bath shop–fits on the block. What happens behind the scenes can be monitored by more competent regulators than zoning allows. And yes, breweries with restaurants and taprooms fit here and getting more beer in my neighborhood is really the goal of this argument.

Smart manufacturing

Modern automation does not automatically equate to noise and disruptive traffic. Hobbyists have computerized cutting machines and 3D printers in their garages. They’re using them to create everything from robotic arms to personalized bobbleheads. Today’s machines are a tool, just like a box of chisels. Mechanization has a place in neighborhoods and should not bump manufacturers out of flexible, local workspaces. Even the largest manufacturers in the world are building medical devices in buildings that resemble offices. Smart manufacturing looks like the GM plant in Kokomo, Indiana that’s manufacturing respirators.

Accessory Distribution

Distribution in residential areas could look like the original Amazon headquarters. Or it could look like the Amazon brick-and-mortar stores, with a bookstore or robodega as a chaperone use connected to a behind-the-scenes miniwarehouse that can double as a local distribution hub. Localization becomes more pertinent in a post-Covid landscape as we find centralized distribution centers too large to clean or staffs too large to protect. A mesh of smaller hubs covering the entire city would be resilient even if one or more had to close for disinfecting.

Distribution may end up being a larger business than the storefront, an inversion that is currently forbidden for accessory uses. But inversion would be a good thing if it allows for shorter trips by smaller delivery vehicles in a organization that is not broken when a pandemic takes out a central hub.

Arts and Recreation

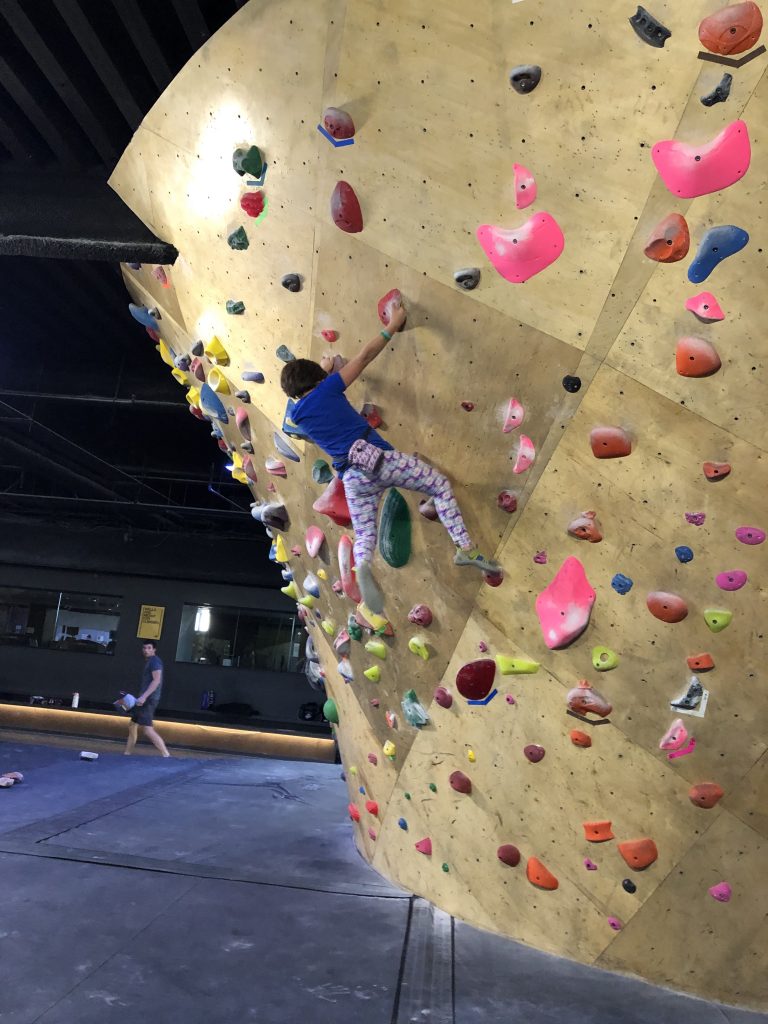

Recreational uses are the most incidental industrial establishments. Zoning fails to create areas large enough to accommodate their footprints outside of industrial zones. This pushes the uses away from the folks that use them. We also shove art space into industrial zones as a nod to the pioneer culture of artists, taking over abandoned buildings and becoming the vanguard for gentrification. Both should be welcomed back into our residential areas. Split block averaging will move away from the thin gerrymandered zones that are less than a single lot wide. Flexible footprints and modified interior spaces can allow for varied uses like galleries, specialty gyms, or bowling alleys to move closer to their customers.

The upshot of these four neighborhood industrial uses is that residential zones should look a lot like the residential uses we already have. Take for example all of the features that are in this single residence in downtown San Francisco, from the bat-cave garage and car elevator, to the oversized kitchen and secondary catering kitchen, through the art gallery, and out to the detached sauna/gym/office.

Incorporating industrial uses in our neighborhoods departs from this single-family monstrosity in only one way: neighborhood industrial benefits the community. Our communities are better with more industry and less of these absurd, insular fortresses.

But the bat-cave does perform one service. It illustrates the farce of a zoning ordinance always deferring to single-family detached housing. An ordinance that allows every insane personal luxury, but does not afford the same flexibility to the community at large, is necessarily a failure. That, among some other things, is why we need to reintroduce industry to our residential neighborhoods. I will cover those next week in the final installment of this series.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.