Learn more about the ambitious proposal to build new high-speed transit connected hub-cities at the upcoming October 9th event.

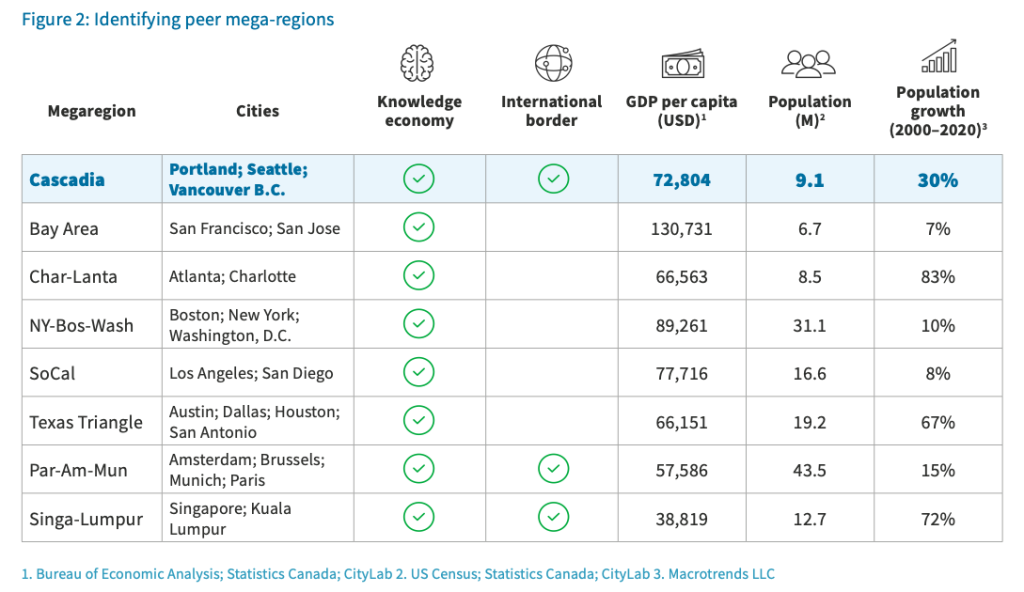

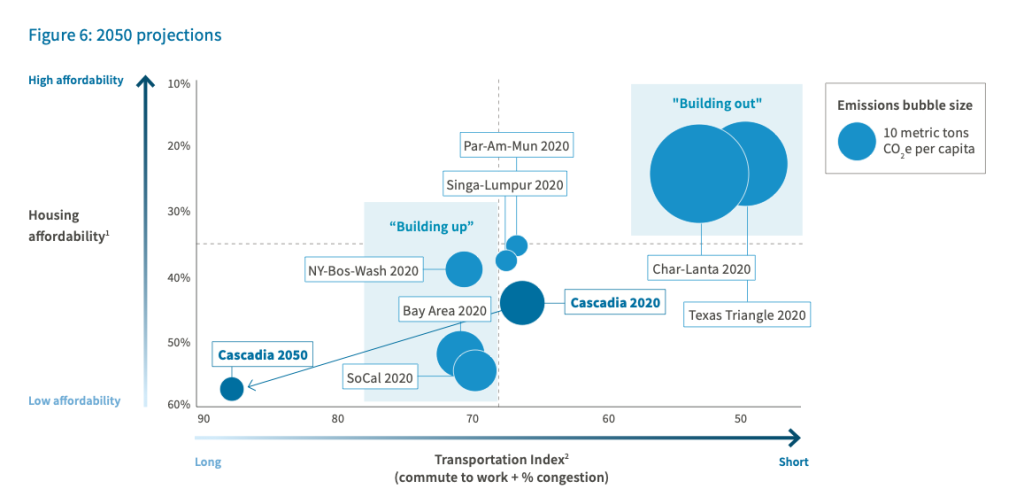

Skyrocketing housing costs that displace established residents. Ever increasing commute times. Development that sprawls into environmentally sensitive areas. Stubbornly high carbon emissions. A new consultant report, Cascadia Vision 2050, completed for Cascadia Innovation Corridor (CIC) depicts a future in which present day affordability and environmental problems worsen as the Cascadia mega-region, which includes Seattle, Portland, and Vancouver, British Columbia, continues to surge in population by a projected 30% to 12 million residents by 2050.

To put the projected problems in context, the report cautions that on its current trajectory the Cascadia mega-region will have higher housing costs than San Francisco or New York City by 2035 and longer commutes times than Los Angeles or San Jose by 2040.

But could there be another way? Is it possible for the Cascadia mega-region continue to grow its vibrant economy without exacerbating economic inequality and displacement or sacrificing its natural beauty?

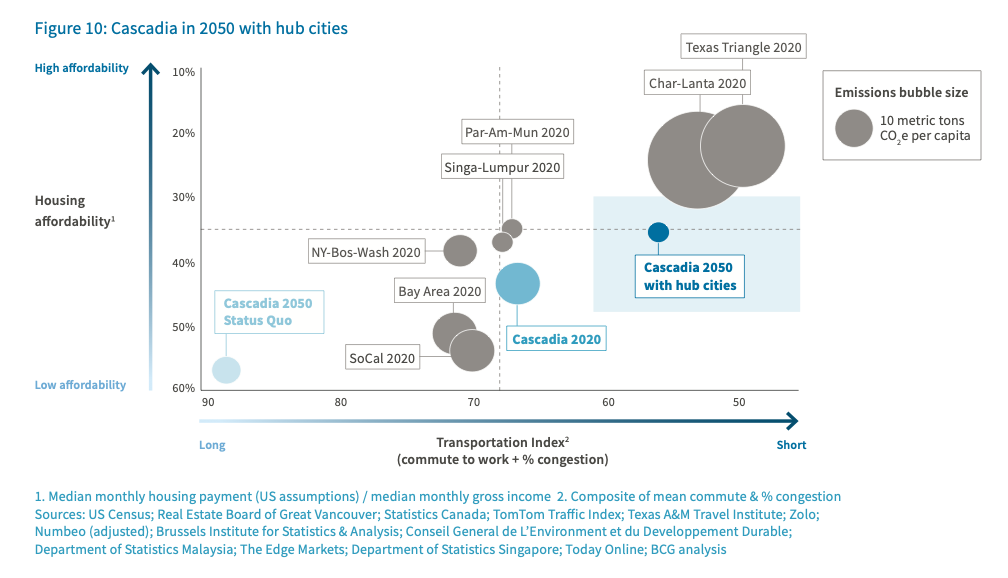

The answer is yes, for the report’s authors, but only if the Cascadia mega-region halts its current development trends and reinvents growth paradigms around high-speed transit that connects “existing urban centers to expanded hub cities with good jobs, affordable housing, and world-class culture.”

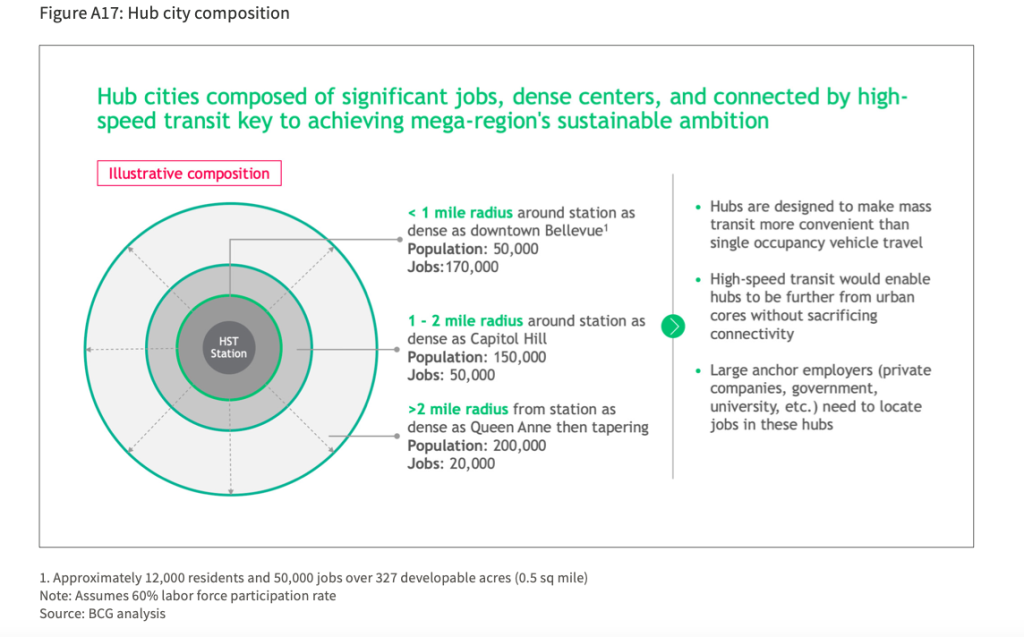

These hub cities, which would be constructed on currently undeveloped land, would be smaller than existing metro areas, but they would not be bedroom communities. Instead the hub cities would be planned as dense, walkable, mixed-use communities offering affordable housing and employment opportunities to residents.

Cascadia Vision 2050 is ambitious, something the CIC has acknowledged. “This vision is not easily achieved–to date, no other mega-region in the world has done it,” reads the report’s introduction.

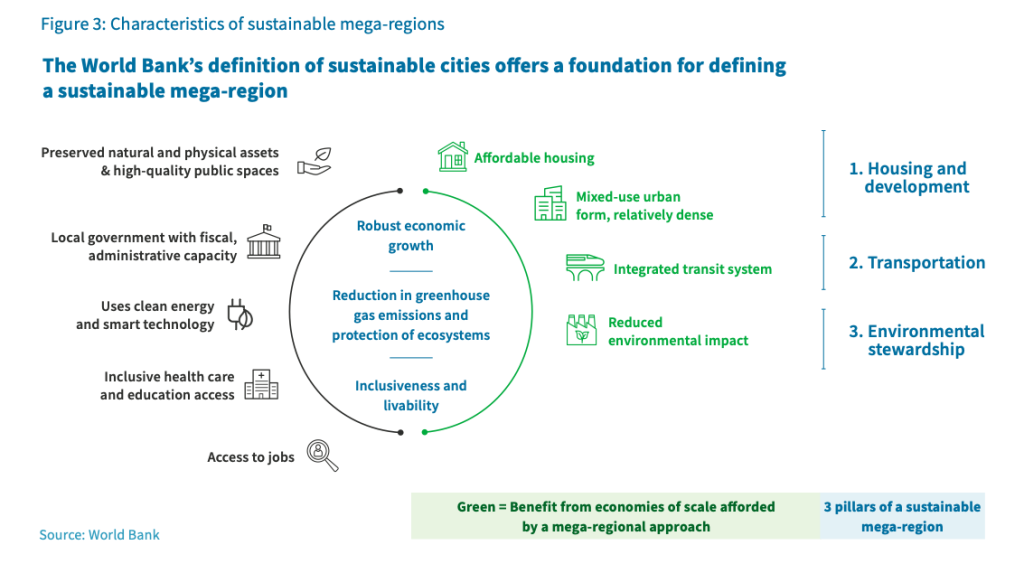

Headed by former Washington Governor Christine Gregoire and Greg D’Avignon, President and CEO, Business Council of British Columbia, the CIC has a staunchly pro-growth stance. But the organization also believes that with the implementation of innovative strategies, it is possible for the Pacific Northwest to continue its rapid growth without harming the region’s natural environment or diminishing quality of life for residents. The CIC has divided its goals for the future sustainable mega-region into three categories:

- Housing & development: across the mega-region, median housing cost is equal to or less than 30% of median income;

- Transportation: projected population growth can be absorbed without an increase in traffic congestion;

- Environmental stewardship: proportional carbon emissions reduction of 80%, from 66 to 14 million metric tons by 2050 in order to meet Paris Climate Accord targets.

Some critics would likely argue that such goals cannot be met without slowing growth. Growing pains can already be felt across the Cascadia mega-region, and it can be stomach churning to contemplate where the future may be headed. But could the introduction of high-speed transit and new hub cities planned for density and walkability help Cascadia continue to grow while also becoming the world’s first sustainable mega-region?

What is a mega-region?

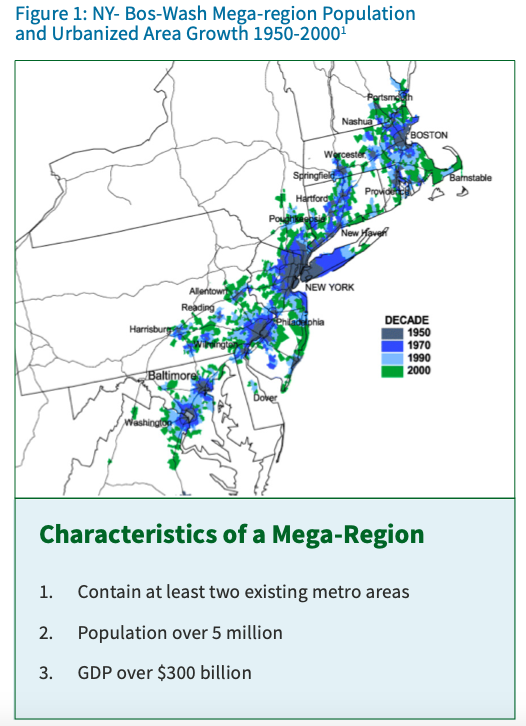

As the world’s population has urbanized, mega-regions have grown in number and influence across the globe. A mega-region is broadly defined as a population center composed of at least two metro areas, over five million inhabitants, and a gross domestic product (GDP) that exceeds $300 billion. According to CityLab, the Cascadia mega-region currently ranks 16th globally, just below Char-Lanta (Charlotte-Atlanta). Many experts have presented evidence that these mega-regions play an outsized role in the global economy, sometimes eclipsing the power of the local jurisdictions and even nation states.

A study of mega-regions demonstrates that they often exhibit very different urban development patterns. Take for example the world’s two largest mega-regions in population size and GDP, NY-Bos-Wash (Boston-New York-Washington, D.C.) and Par-Am-Mun (Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels, Munich). The rise of NY-Bos-Wash accompanied the growth of the American highway system and the sprawling urban development patterns that sprung up around it, a trend that has worsened in more recent decades. On the other hand, Par-Am-Mun has a denser built environment largely planned around transit as a result of the influence of pre-automobile city planning and a greater emphasis on trains for transportation.

Cascadia Vision 2050 describes the birth and evolution of mega-regions as occurring when geographic and economic boundaries between cities become blurred as people and economic activity spreads across jurisdictions. In this scenario, the traditional approaches to urban and regional planning can fail to meet new challenges because they tend to be geographically and jurisdictionally bound. For the Cascadia mega-region, the NY-Bos-Wash appears as a cautionary tale–showing how a failure to plan collaboratively can result in a mega-region that sprawls outward, increasing congestion and decreasing affordability.

The importance of high-speed transit

The average commuter in the Cascadia mega-region already spends 18% more time commuting than they did in 2011, the report estimates, and as mentioned earlier, that statistic is projected to continue to increase. There has also been a rise in so-called “mega-commuters” (people who commute more than 90 minutes each way) to the tune of 70% to 80% in both Seattle and Portland since 2010.

These commuting patterns have disastrous effects on both the economy and the environment in the Cascadia mega-region. Current commuting patterns equate to the $7.1 billion of lost productivity per year and transportation remains the mega-region’s the highest contributor of carbon emissions with single-occupancy vehicles contributing 4.1 million metric tons of carbon each year.

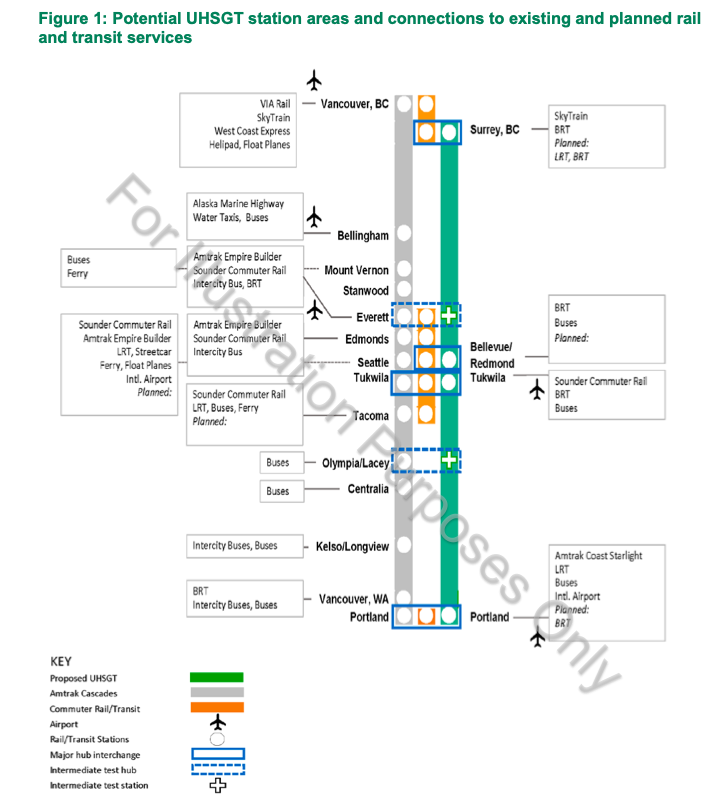

While Cascadia Vision 2050 does not expressly cite the ultra high-speed rail study funded by the Washington Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), the CIC is known to be an advocate for ultra high-speed rail to connect Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver by 2035. So far the economics seem to be in the proposal’s favor; a business case analysis published last year showed ultra high-speed rail could stimulate $355 billion in economic growth and create 200,000 new construction and ongoing service operation jobs.

Currently, another high-speed rail study is underway evaluating governance structures, funding and financing options, and outreach activities. A report is expected to be complete in December 2020.

Advocates are hopeful that the plan will continue to progress forward to meet its 2035 completion date.

“Timely implementation of high-speed rail can help achieve our climate goals in addition to addressing population growth and housing affordability. By connecting downtown hubs, employment centers, and mid-sized cities, people can live and work where they want,” said Paige Malott of the high-speed rail advocacy group Cascadia Rail. “For example, a one-hour high speed rail connection between Vancouver and Seattle creates an easy commute between urban centers, and connections to smaller cities, such as Mount Vernon or Bellingham, gives people the choice of small town living without spending hours in traffic.”

Hub cities as a new paradigm for equitable mega-region growth

While the introduction of high-speed transit would help to alleviate congestion and open a wider array of housing choices, the Cascadia mega-region may still need to do more to grapple with its housing affordability crisis. Looking at population projections, Cascadia Vision 2050 argues that even if existing large and mid-sized cities are zoned for greater density, they still won’t be able accommodate all future residents.

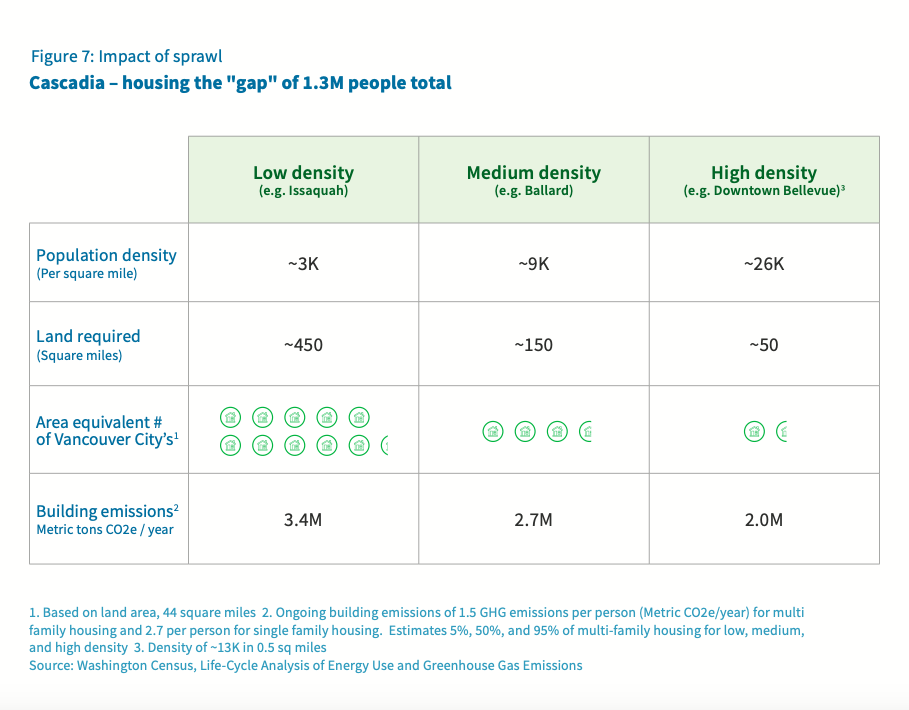

Of the three million projected residents, “850,000 people will be accommodated through continued densification throughout the mega-region, about 650,000 people will be accommodated through increased densification around planned transit projects and up to 800,000 people will be accommodated through accelerated densification of mid-sized cities throughout the mega-region.” Those numbers account for projections account for 2.3 million people, leaving a gap of 1.3 million additional residents.

The report explains that among the seven peer mega-regions studied, two urban development patterns emerged as responses to explosive growth: growing up or growing out. Assessing the pros and cons of both approaches, Cascadia Vision 2020 argues that geographic constraints make growing out not only undesirable, but in some cases geographically impossible, while growing up will still fail to meet projected growth unless drastic changes are implemented. For example, the report cites that to accommodate the influx of 1.3 million people through upzoning, nearly 40% of single-family homes in Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver. would need to be replaced by fourplex buildings, a change that while not impossible, would likely meet stiff political opposition. Hence the proposed hub cities, which the report proposes be founded on these main features:

- Hub cities should be built on undeveloped land 40-100 miles from urban cores;

- Designed for high speed transit and multi-modal local transit (walking, biking, etc.);

- Include dense housing for 300,000-400,000 people;

- Have 200,000 jobs.

Cascade Vision 2050 projects that if a suitable number of hub cities are constructed, the region can change its trajectory on congestion, lack of housing affordability, and carbon emissions.

What examples of hub cities can Cascadia look to for inspiration?

Forest City, Malaysia, located 30 miles from Singapore, is presented as an example of what a hub city of the future could look like. Construction of the city began in 2014, and by 2050 it is expected to be the home of 750,000 residents. Connected by high-speed rail, ferries, and other multi-modal transit options to Singapore and Johor, Malaysia, Forest City has been designed for walkability, proximity to employment, and affordable housing. Green infrastructure and other environmentally sensitive design features are also planned to boost quality of life for residents.

The Cascadia mega-region still has a long way to go before it begins development of its own hub cities, and there are sure to be detractors who will argue that the projections for growth cited in Cascadia Vision 2050 won’t hold up over time. Still the fact that King County alone needs to build, preserve, or subsidize 244,000 net new affordable homes by 2040 to tackle its own housing crisis may strengthen the argument for building new urban centers like hub cities.

Other detractors may point to the fact that the alignment of proposed ultra high speed rail bypasses both existing urban centers, like Downtown Seattle and Vancouver, making the argument for hub cities altogether too convenient for developers.

Either way, the high-speed transit connected hub cities proposed by Cascadia Vision 2050 represent a new topic of conversation for the future of a rapidly growing mega-region. If you are interested in participating in the conversation or learning more, be sure to sign up for Connecting the Cascadia Corridor – A Cascadia Innovation Corridor Virtual Forum, on Friday, October 9th. Plus, keep an eye out for future CIC-hosted events.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.