Walking among the gleaming towers in Seattle’s South Lake Union, there is a buzz in the air. The aroma of tantalizing restaurants, the din of construction noise, the waves of traffic, and the bustle of commerce are the fruits and frustrations of a fast-growing neighborhood. What’s not obvious to the passerby is that the very buildings that changed the city’s skyline also changed the future of the region’s farms and forests. Hidden in plain sight among the skyscrapers are 100,000 acres of permanently conserved land some 25-plus miles away.

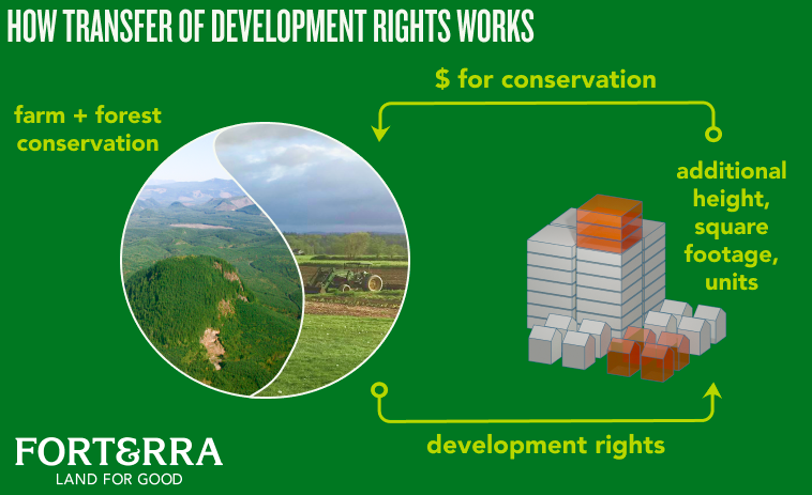

Seattle is one of many cities in the central Puget Sound region that uses a real estate tool called transfer of development rights (TDR). In brief, TDR is a market-based land use tool that promotes responsible growth in places it is desired and assists in the conservation of agricultural and forest lands. TDR gives landowners the option to sell the development value from their property as an alternative to building. TDR is fair and voluntary for both developers and landowners.

Through individual, market-based transactions, the development rights — a private real estate asset representing the development potential (and value) of property — are then transferred from privately owned farmland, forestland, and natural areas to places like South Lake Union that can accommodate additional growth. Landowners sell the development rights at market rates, while developers gain additional building height, square footage, or other value.

The result is powerful. Cities grow more efficiently within their existing urban footprints and the private market drives conservation of lands that are important to the sustainability of the region. This program is working to great effect in Seattle, Bellevue, and other cities, but there’s an additional benefit available to cities.

How do we pay for all the other stuff that cities need as they grow — parks, transit, roads, sidewalks? More growth requires more infrastructure, and infrastructure is expensive. Forterra, a Washington-based nonprofit which supports healthy environments and resilient communities, designed state legislation to address this challenge. Adopted in 2011, the Landscape Conservation and Local Infrastructure Program (LCLIP) takes an innovative approach to meeting local and regional needs. Available to 35 cities in Pierce, King, and Snohomish Counties, LCLIP creates a new source of revenue for cities to fund community improvements that support growth, making urban neighborhoods more functional, more welcoming, and more accessible.

It works by combining TDR with a form of revenue sharing from counties. As new construction happens, the property tax base grows. Cities that commit to using TDR get to keep some of the property taxes from new construction that otherwise would go to counties. They can spend that money on public improvements to growing neighborhoods where new construction is using TDR. Counties benefit from the thousands of acres of land conserved through the private market as well as from lower future costs of service to growth in rural areas. Seattle is on track to earn over $30 million to pay for mobility improvements, streetscaping, parks, transit, and a community center.

The next challenge is to replicate this success across the region. If all 35 eligible cities use LCLIP, the resulting conservation could be transformative. 650,000 acres — about the size of three Mount Rainier National Parks. How do we broaden participation in this program?

Forterra is currently running bills in the state legislature that would make two important changes to LCLIP based on feedback heard from cities around the region. First, the value proposition to cities would improve, giving them access to more revenue for infrastructure. But public improvements aren’t the only need our communities face. For growth to occur in cities, people need to afford to live in them, so the second change expands the definition of infrastructure to include affordable housing. If these bills pass (SB 5823 in the Senate and its companion, HB 1243 in the House), cities would be able to fund more investments in their neighborhoods while simultaneously achieving landscape-scale conservation, all through the private market.

LCLIP is the only program of its kind in the United States. It recognizes that our rural and urban communities are intrinsically linked to each other. Our farms and forests provide our families with clean air and water, fresh produce, and places to recreate. Our urban cities provide economic centers that house people and jobs. Both are essential components of Washington’s economy and high quality of life. If we want to provide future generations with options, both our urban and rural communities must flourish.

The design of LCLIP is flexible enough to work for highrise construction in metropolitan centers like Seattle, Bellevue, Tacoma, and Everett; mixed-use growth in suburban cities like Issaquah, Puyallup, and Lynnwood; and in the redeveloping town centers of Mountlake Terrace and Sammamish. It is bringing new resources to support growth in Seattle and can do the same for other cities.

Nick Bratton (Guest Contributor)

At Forterra, Nick Bratton (MPA, MS) collaborates with communities to balance regional growth and conservation of resource lands in ways that meet local needs. He has designed market-based conservation programs in counties and cities in Washington, including shaping two state laws creating a regional marketplace that has protected over 100,000 acres of farm and forest land. Nick is also an avid adventurer, world traveler, and published travel writer and photographer.