Editor’s note: This is a two-part article cross-posted from The Northwest Urbanist, see Part 1. Yesterday, Scott covered the points of aesthetics and accessibility, and costs and funding.

A group of Seattle residents called Park My Viaduct is campaigning to convert the city’s waterfront freeway into a linear park, akin to New York’s High Line. They are proposing to save 14 blocks of the concrete double-decked structure, put the idea to a vote in the November 2015 election, and construct safety improvements at a cost of $250 million. But this idea is in opposition to the entire purpose of the ongoing waterfront reconstruction, which has already had a public participation process and is currently being built. The entire viaduct should be demolished as planned.

Don’t start the process over

A major point of the campaign is that similar elevated parks in New York and Paris have attracted large amounts of private redevelopment around them, contributing to tax revenue and neighborhood vitality. This is more likely to happen with implementation of the approved Waterfront Seattle plan because waterfront businesses have been able to get involved and shape it to meet their needs. At 25 feet high and significantly narrower, the High Line is less than half the size of the viaduct and runs through an area that was mostly dilapidated industrial properties, so it’s not directly comparable. If Park My Viaduct was around earlier a case could have been made for keeping the lower deck of the three-quarter mile section south of King Street which was demolished in 2011; there the viaduct ran along the rear of the seaport beside railroad tracks and could have provided a scenic connection to the Duwamish River crossing.

Much of the land uses adjacent to the viaduct are parking lots and loading docks, and there’s little reason to think that would change because there’s a bike path five stories above. Foster said there have been recent changes to development regulations for the core area between Columbia and Union Streets that includes encouragement of more hotel and residential uses, screening of parking from the street, and no changes to height limits. He also said the City is putting together new urban design standards for properties facing Alaskan Way.

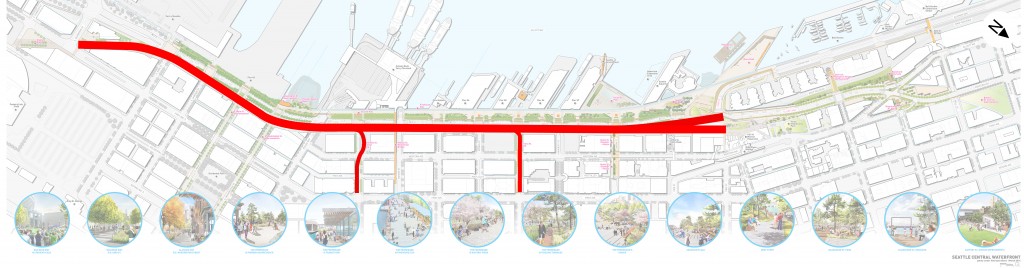

But the opportunity to voice their opinion and work the viaduct into the waterfront plan has mostly come and gone. Since 2011, Waterfront Seattle has hosted or attended some 300 events for community outreach and collecting public feedback. It is unreasonable for this minority to expect to be seriously acknowledged when the city is becoming invested in the current plan after such a long and thorough process. Preserving the viaduct would also interfere with a number of planned features, including the Railroad Way promenade, a new Marion Street pedestrian bridge, and the Overlook Walk. It would also directly prevent the Alaskan Way redesign from happening, though the size of that new street has its own problems.

A serious hazard and questionable legitimacy

The campaign didn’t exist until the viaduct’s replacement tunnel was delayed in December 2013. (The replacement tunnel is an entirely different boondoggle that other writers have covered well.) But the hastily-formed effort has already received funding from developer Martin Selig for a feasibility study. The engineers’ findings shouldn’t be surprising; the viaduct is a known hazard to life and property. The state transportation department’s regular inspections indicate the viaduct has been sinking since being damaged in the 2001 Nisqually earthquake. In the video above, a (very) dramatic simulation of a future earthquake shows how the viaduct could collapse without reinforcements.

Park My Viaduct’s legitimacy, limited as it is, would improve if they answered basic questions about their proposal; multiple inquiries and asking when their feasibility study will be released went unanswered. Their silence is reminiscent of the Griffith family, who built the waterfront Ferris wheel without public input and who are now attempting to quietly build a private gondola in public right-of-way. The gondola would be equally problematic and, ironically, hinges on the viaduct being demolished. Foster said because of many policies that are in place, such as Union Street being a protected view corridor, the City doesn’t see a path forward for the project.

This proposal is also the same kind of misguided activism that led voters in the last election to decline yet another effort for a citywide monorail system. And, not surprisingly, local activist Elizabeth Campbell has been involved with both. She’s on the campaign’s steering committee and led the monorail campaign so poorly that some of the people she listed as supporters were opposed to the project. The monorail vote failed by 62 points.

While new park space is needed downtown, putting it on top of a crumbling and inhuman-scale freeway structure that is slated for removal is the wrong way to do it. The waterfront plan has already been developed after a long period of public participation, and that should not be preempted by a haphazard proposal that threatens the viability of the entire project. The Alaskan Way Viaduct must be demolished as planned and as soon as possible so that Seattle can move forward with transforming its waterfront into a world class public space.

Scott Bonjukian is a graduate student at the University of Washington’s Department of Urban Design and Planning. He writes about local and regional planning issues at his personal blog, The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.