Dotted across Seattle are scores of commercial districts, often lining the city’s major thoroughfares. They are the centers of community where people assemble, conduct commerce, and exchange ideas. From North Seattle to South Seattle, they are steeped in history, diversity, and character. No two are exactly the same; they are entirely unique. But what makes these places so beloved by local residents is that they are people-oriented.

A place truly connects with people when it is designed to interact on a human level as opposed to a mechanical level. Look around and what you’ll notice in people-oriented commercial districts is that the streets, buildings, and uses directly engage with people on foot. Sidewalks are generous, well maintained, offer opportunities for respite, and maybe even a little bit of earth. Moving from one side of a street isn’t a chore, it’s a comfortable and convenient experience that draws you from one point to another. Buildings are relatively continuous, detailed, vertically scaled, and have ample transparency on the ground floor. Spaces for uses vary in size, but generally are small in frontage. Uses are diverse throughout, but particularly active and practical for daily needs and wants when located at street level. Mix these qualities together and you probably have spaces that are tailored to people.

Yet, this doesn’t happen entirely by accident.

Over the course of the past few years, Seattle has engaged in an effort to revamp commercial districts through regulatory changes. One such change was enacted in 2013 by the adoption of minimum density rules. These rules apply only to pedestrian retail areas (known as “Pedestrian Zones” or “P-zones” in the land use code) in urban centers and urban villages, and require the development of denser commercial and mixed-use projects. Minimum floor area ratios (FAR) are set based upon maximum zoned height and ultimately push development to cover more lot area and build upward. But the latest changes go much further.

In early May, the Seattle City Council approved (Ordinance 1124770) a suite of land use code changes for Pedestrian Zones. In sum, the changes touched on new permitted uses, transparency of ground floor spaces, overhead weather protection regulations, residential allowances, live-work units, and the location of Pedestrian Zones themselves. The new regulations came into force on June 15th.

The land use code describes a Pedestrian Zone as “an intensely retail and pedestrian-oriented shopping district where non-auto modes of transportation to and within the district are strongly favored.” Pedestrian Zones are typically located within Neighborhood Commercial zones (NC1, NC2, and NC3), but they can also be found in a limited number of Commercial zones (C1 and C2). Pedestrian Zones are formed in two ways: the mapped area of the designated Pedestrian Zone and the Principal Pedestrian Streets that lie within Pedestrian Zones. The distinction here is important. Some regulations apply throughout a Pedestrian Zone while more specific requirements only apply along designated Principal Pedestrian Streets.

In the spirit of this, Pedestrian Zone regulations directly prohibit drive-through lanes for businesses, restrict the location of parking to the rear of a property or within a building, and discourage driveways that cross a sidewalk along Principal Pedestrian Streets. Also in the regulatory mix are reductions/waivers for parking requirements and specific set of active uses required along the street-level frontages when located along a Principal Pedestrian Street. However, the the latter two policies were revised in the recent code change.

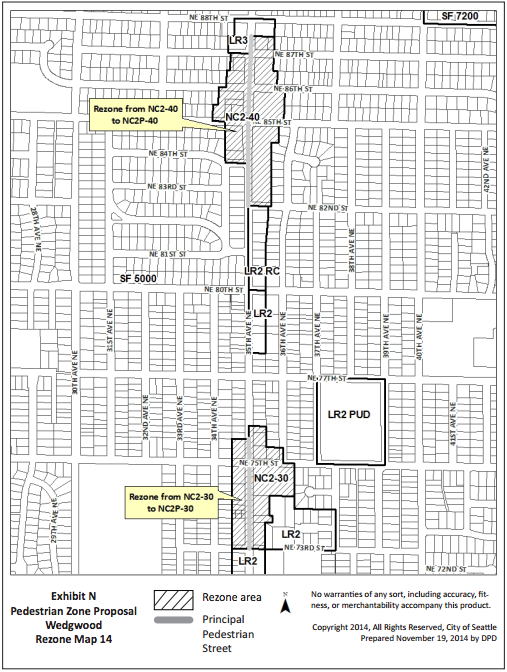

Expansion of Pedestrian Zones

The most noticeable change from the Pedestrian Zone code update is the expanded number and extent of Pedestrian Zones. At the outset of the regulatory changes, Seattle had 33 Pedestrian Zones designated across all quadrants of the city. But nearly 40 locations were added to the City’s official zoning map. A few of the additions were merely extended Pedestrian Zones (e.g. Fremont, Upper Queen Anne, and Green Lake), but most of these additions were entirely new designations for commercial districts (e.g. Wedgwood, Loyal Heights, and South Park). Until the regulatory changes, Pedestrian Zones covered just 24% of Neighborhood Commercial zoned land (1.2% of the city). A few prominent locations (e.g. Uptown, Ballard, and the University District) were excluded from the code changes due to ongoing planning updates within them.

Street Level Uses, Live Work, and Residential

The Pedestrian Zone designation is focused on active street level uses. Naturally, the land use codes calls for these uses to be located on Principal Pedestrian Streets to drive foot traffic. But this desire for active uses does come with some restrictions. As you can see in the table below, the uses in the two left columns were the only uses permitted at the street level of buildings in the Pedestrian Zone. Meanwhile, the uses on the right hand side were prohibited. The regulatory changes opened up a wider variety of uses within Pedestrian Zones, including community gardens, a larger spectrum of entertainment and institutional uses, food processing and craft work, and limited amounts office and heavy sales and services.

Office space is not typically seen as an active use due to low customer volumes, but the City wants to experiment with allowing small office spaces on the ground floor of structures in Pedestrian Zones. Office uses may be located in any street-level, street-facing structure so long as there is no more than 30 feet of frontage dedicated to office uses within it. The same restriction applies to heavy sales and services, which are typically uses like laundromats, furniture stores, or major goods suppliers.

In addition to the above, some clarity was brought to how live-work units should be designed along Principal Pedestrian Streets. The work aspect of a live-work unit must now extend the full width of the unit along the street and have a minimum depth of 15 feet from the front of the unit. No residential (live) features are allowed within the business (work) space. That means no kitchen, bathroom, sleeping, or laundry facilities. Live spaces must be designed beyond this work area or entirely separated. The land use code also now calls for clear business signage for all live-work units. Signage must be conspicuously located on the outside. And, each owner of a live-work unit must have a copy of their business license located within the unit on file. Those changes reflect a general concern that many live-work units are merely being converted to townhouse/rowhouse-like units instead of bonafide ground floor businesses with living space. Beyond these changes, the existing land use code maximum for total live-work space remains in force: live-work units are restricted to 20% of the street level frontage of a structure.

While not specifically live-work, a small change to the residential use rules resulting from the code change could be big. Street level residential uses are now permitted in many more Neighborhood Commercial and Commercial zones. But, the code change could allow up to 17 new areas not designated as Pedestrian Zone designation, but zoned as commercial, to allow street level residential uses. And, a departure from the general development standards could grant up to 50% of a street level frontage in Pedestrian Zones with residential uses.

Overhead Weather Protection

Given Seattle’s relatively rainy environment, overhead weather protection provides pedestrians a good measure of relief from the elements. Overhead weather protection often comes in the form of awnings, canopies, and marquees projecting from a building’s facade and over a sidewalk. The City wants to encourage the proliferation of these features throughout pedestrian-designated areas. To do that, two sections of code were modified: the first in the land use code, and the second in the transportation fee code.

Overhead weather protection is now required for frontages of structures located on a Principal Pedestrian Street. A minimum of 60% of the street frontage for the structures must have some form of weather protection. And, these overhead weather protection features must be at least six feet in width. Additional guidelines in the land use code describe how the overhead weather protection should be designed for lighting, overhead clearance, and conflicting street elements.

Since overhead weather protection is typically located over the public right-of-way, they require review, permission, and the payment of fees. With this in mind, City staff recommended that fees be waived to encourage the deployment of overhead weather protection by property owners and developers. The adopted legislation specifically dropped the street-use fee in its entirety (it was originally $0.51 per square foot). The primary intent of this change was for commercial areas, but technically, the removal of the fee applies to all areas of the city regardless of zone.

Transparency

For structures with non-residential uses on ground floor street frontages, the land use code calls for a minimum amount of transparency through structure facades. 60% of street-facing facades between 2 feet and 8 feet above the sidewalk must be designed as transparent (yes, it is that specific). In other words, people should be able to view into and out of the structure with minimal obstructions. Clarification was added by the code changes to ensure that window tinting, shelving, permanent signage, or other fixtures do not unreasonably impede the transparency of windows. In many instances, retailers and street level businesses have gone to extremes to foresake their primary frontages with blank walls or excessive clutter, which is detrimental to the quality of districts that dependent upon active foot traffic. This change gives the City greater power to enforce active frontages instead. On the flipside, the code changes also created some flexibility to challenging sites where vehicle access options are limited. In specific instances, up to 22 feet of vehicular access entries on a frontage could be excluded from the street frontage facade calculations for transparency, thereby reducing the overall transparent frontage requirements.

Individually, these changes may not seem like much, but together they really add up to enhance the overall quality of Pedestrian Zones while also offering greater flexibility. So, what do you think the City could do next to enhance pedestrian-oriented commercial districts?

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.