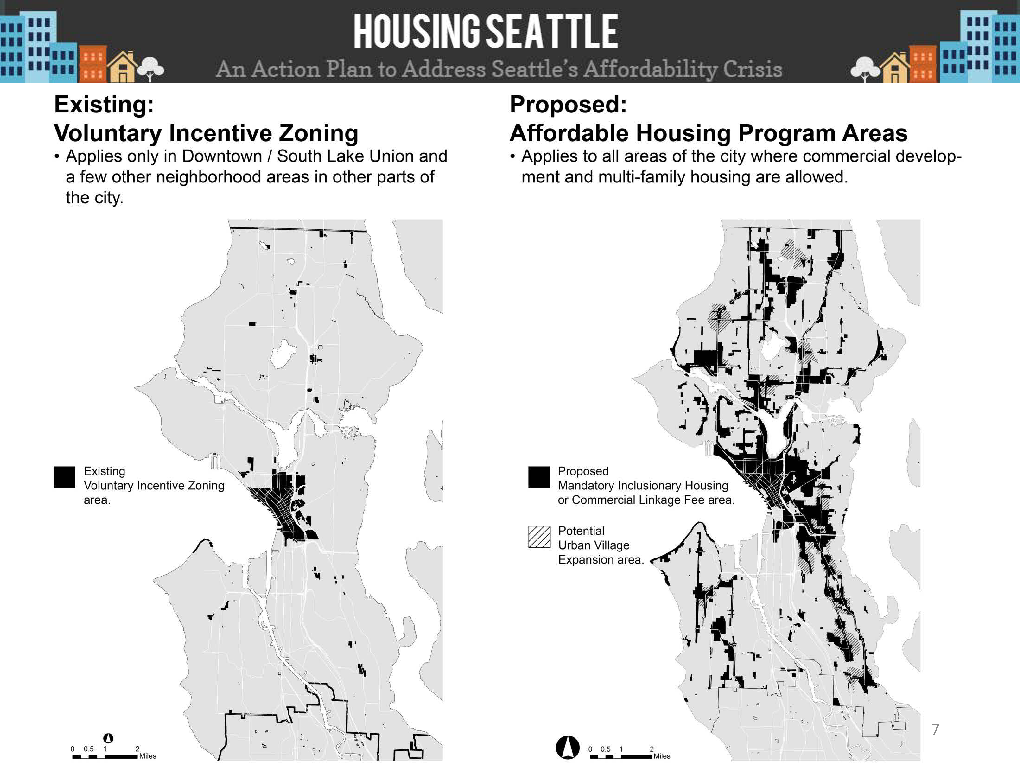

The Seattle City Council is considering a mandatory affordable housing program linked to commercial developments. The program is no longer just a commercial “linkage fee” (otherwise known as an “impact fee” in Washington state), and now consists of two options: developers either pay a fee for building affordable units, or build the affordable units themselves. The program aims to build 6,000 affordable units for households earning 60 percent or less of the area median income (AMI) over the next decade. This is just one policy of 65 recommended by a committee of housing experts and advocates convened by Mayor Ed Murray last year.

Program nexus

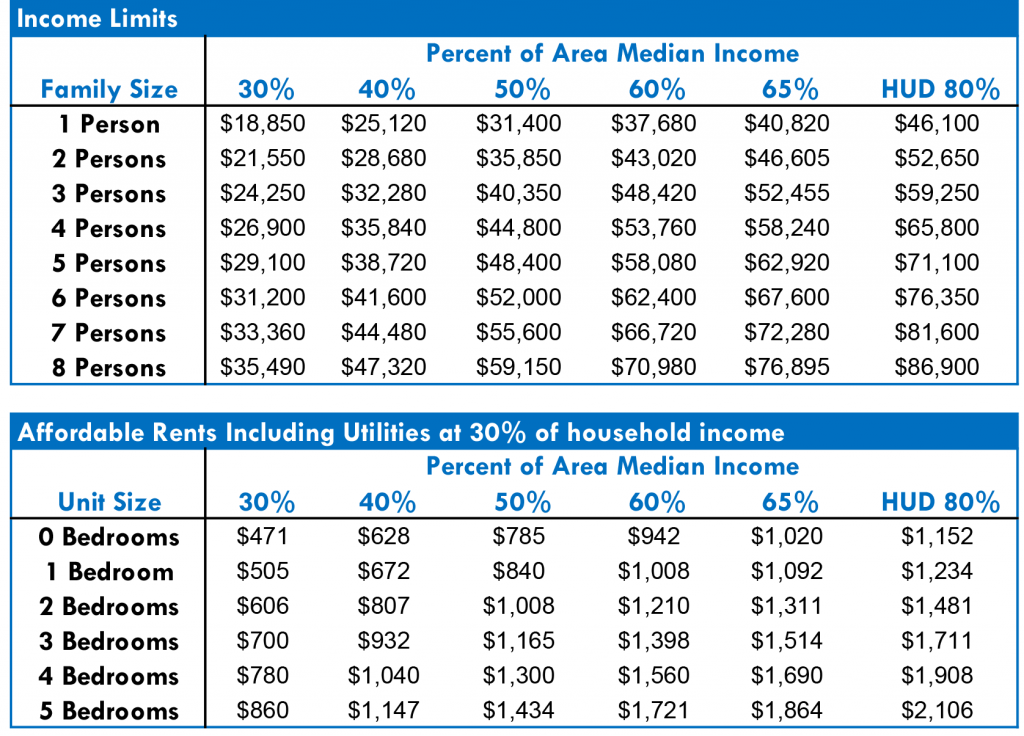

New commercial enterprises like offices, professional firms, retail stores, restaurants, and entertainment venues are bringing economic growth and high-wage jobs to Seattle. But these developments also employ many low-wage workers like custodians, clerks, drivers, security guards, and waiters who are severely burdened by rising housing costs and long commutes. New high-wage jobs also indirectly generate many low-wage jobs, and high earning workers are moving into older housing units that would otherwise be available to moderate- and low-wage workers, driving up rents for everyone.

Seattle wants to enable low-wage workers to live near where they work, especially in the urban core, in order to keep the city’s neighborhoods diverse (people of color are most affected), reduce the costs of commuting, and ensure marginalized populations have access to the cultural and career opportunities of living in a major city. To achieve this, the city plans to require commercial developments to mitigate the demand the low-cost housing that they generate.

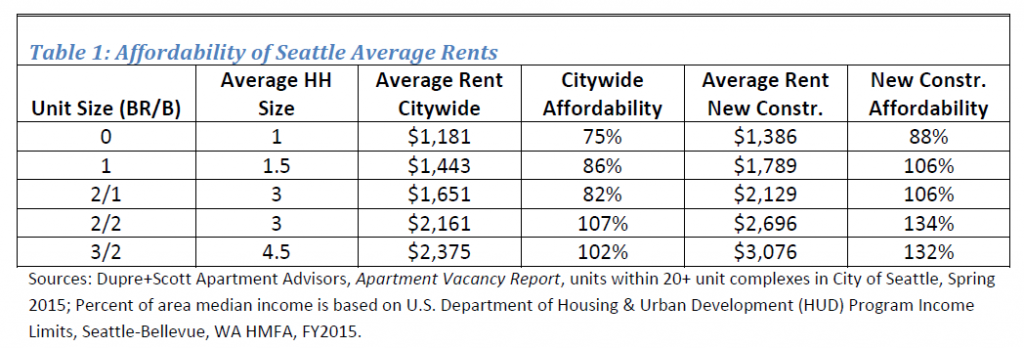

Seattle has a substantial shortage of affordable rental units despite incentive and subsidy programs like the Multifamily Tax Exemption program and the Seattle Housing Levy. The city estimates it has a shortage of: 23,500 units for households at 30 percent AMI; 25,000 units for households at 50 percent AMI; and 9,300 units for households at 80 percent AMI.

Council Bill 118498 will create a new chapter of the Seattle Municipal Code that outlines the requirements of the “Mandatory Housing Affordability through Commercial Development” (MHA-Commercial) program. The bill’s introduction explains the nexus of the program and its main components:

WHEREAS, development of new commercial floor area accommodates new employees, including lower-wage employees, and creates a demand for affordable housing; and…

WHEREAS, the HALA Advisory Committee recommended that the City boost market capacity by extensive citywide upzoning of residential and commercial zones and, in connection with such upzones, implement a mandatory inclusionary housing program for new construction…

WHEREAS, the HALA Advisory Committee recommended that the program offer the alternatives of payment of a per-square-foot fee to fund preservation and production of affordable housing, or construction of affordable housing on-site or off-site…

This bill will not actually create the program itself, and will be followed by implementing legislation next year.

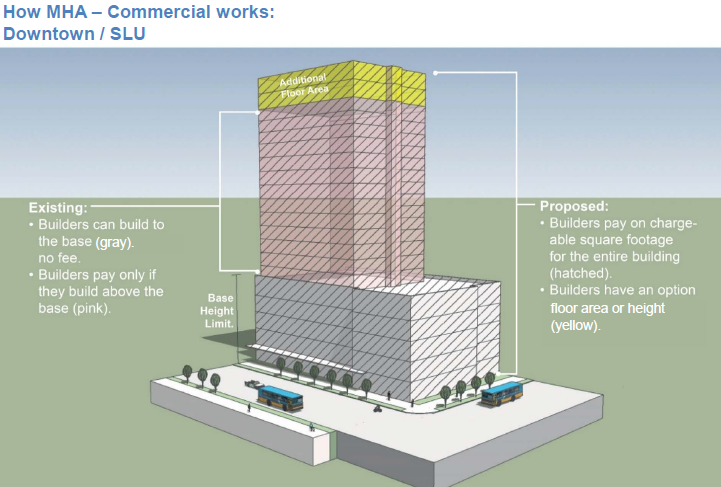

To balance the costs of the MHA-Commercial program to developers, the City Council intends to upzone several areas and allow one or two additional floors above what is currently allowed. Downtown and South Lake Union will be upzoned in summer 2016. Neighborhood Commercial (NC), Commercial (C), Seattle Mixed (SM), Industrial Commercial (IC) zones will be upzoned by spring 2017. The City Council wants to act fast to take advantage of the construction boom.

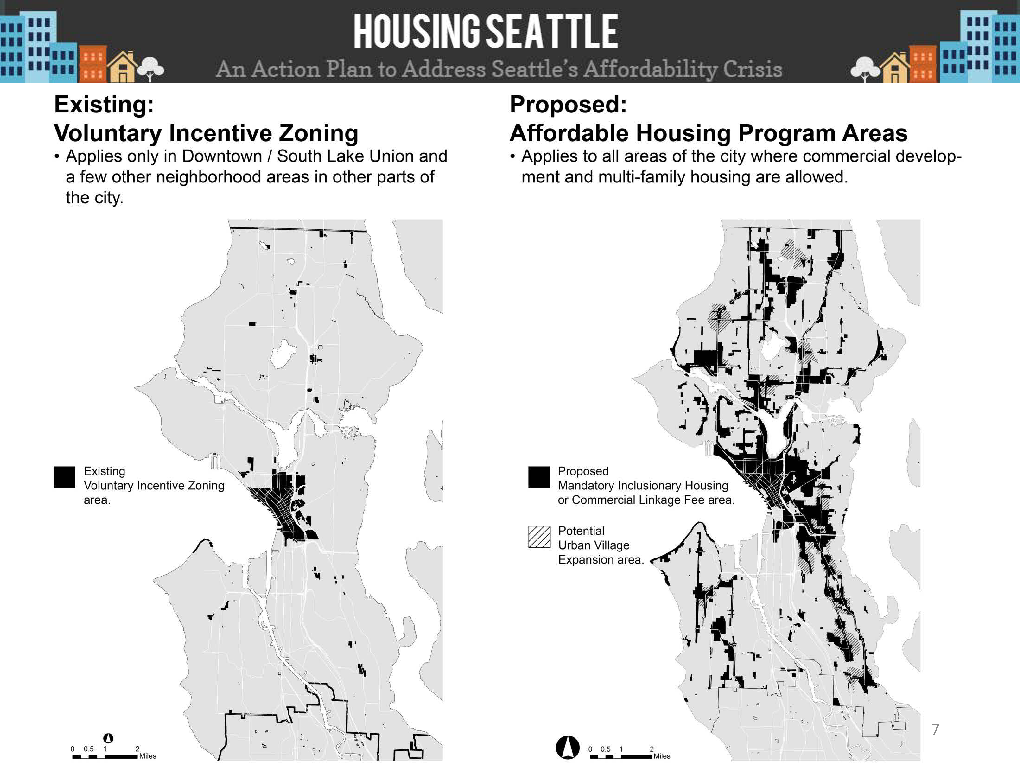

Developers building at least 4,000 square feet of commercial space in these areas will be subject to the program regardless of whether they use the extra height or not (see the graphic at the top of this post). The city also intends to enact a MHA-Residential program, which will be covered in this space at a future date.

Payment option

If commercial developers take the payment option they will pay $8.00 to $17.50 per square foot in the Downtown and South Lake Union urban centers, depending on the zone their project is in. Elsewhere, they will pay $5 to $10. Institutional and manufacturing land uses are exempt from the program. There will also be exemptions for the first 4,000 square feet of required commercial space where buildings front designated pedestrian streets.

The fee schedule is far below the conservative $64 to $80 recommended in a study by David Paul Rosen & Associates, meaning developers will not pay for the full impact their projects have on affordable housing. But the fees are still projected to total $195 million over the next decade.

The fees will go into a fund managed the Seattle Office of Housing for both preserving and building affordable housing. Some of the money will be competitively awarded to non-profit and for-profit developers who build units with rent restrictions based on the tenants’ income. Rental limits will be 60 percent AMI, and homeownership limits are 80 percent AMI. This arrangement must last 50 years. Developments favorable for funding will be located in urban villages, near frequent transit service, and in communities threatened by economic displacement.

Performance option

Alternatively, or in combination, commercial developers could choose to include affordable units in their commercial building as a mixed-use project or commit to building affordable units elsewhere within the same urban village. In the Downtown and South Lake Union urban centers, the amount of rentable residential floor area must equal 5 to 10.6 percent of commercial floor area. Elsewhere, it must be 5 percent. (These percentages are similar to the city’s existing voluntary incentive zoning program.)

The units must be rentals (not open to ownership), be similarly sized as market-rate units, and have a rent limit of 60 percent AMI. This arrangement must also last 50 years. Buildings must have at least three units to be eligible for the performance option, otherwise the developer must use the payment options. Units that are 400 square feet or less must have a rent limit of 40 percent AMI.

Conclusion

To provide a very rough example, the developer of a 300,000 square foot office tower in the Downtown DOC2 500/300-500 zone would have three choices: pay $14.25 per charageable square foot, which without considering any exemptions totals $4.275 million; or provide residential units totaling 8.6 percent of the commercial area, which is 52 units (assuming a typical unit size of 500 square feet); or do some combination of these. In exchange, the DOC2 500/300-500 zone will have a floor area ratio (FAR) increase of 1.0, likely allowing for an additional one or two floors to be built.

Starting in 2018, and every two years thereafter, the DPD Director is required to a submit a report on whether the MHA-Commercial program is meeting its goal of 6,000 units. This number is only part of Mayor Murray’s production goal of 20,000 income-restricted units and 30,000 market-rate units over the next 10 years alone. In its comprehensive plan update Seattle is planning to add 70,000 housing units and 115,000 jobs over the next two decades.

The MHA-Commercial program is a robust and fair way to fulfill much of Seattle’s affordable housing need. It balances new development costs with a potential increase in rentable floor space. The program will contribute to the city’s goals for, healthy, sustainable, and affordable communities no matter how much money residents make.

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.