During a full council meeting on October 17th, 2016, the Seattle City Council voted 7-2 to send Council Bill 118817, popularly known as the “move-in fee legislation,” back to committee. The crowd in attendance at this full council meeting had a decidedly “Occupy” ethos. Clad in red Community Action Network T-Shirts, eyes alight and resistance fists aloft, they plead the case of the despondent tenant during public comment.

On December 12th, 2016, the same council voted unanimously to pass the bill, as amended, and the crowd in attendance was noticeably more diverse. The Rental Housing Association of Washington had just held their annual trade conference nine days prior on December 8th. Attendees of the conference were instructed to show up early to the Full Council meeting in December to block the “red shirts”. Clad in pleat and collar, torches alight and pitchforks aloft, they arrived early as instructed (albeit at the 11th hour) to plead the case of the aggrieved landlord. Between these two council meetings, a special session of the Energy and Environment Committee was held to discuss amendments to the legislation. What is Council Bill 118817, and what happened during the two-month interim to elicit unanimity in the Council Chambers?

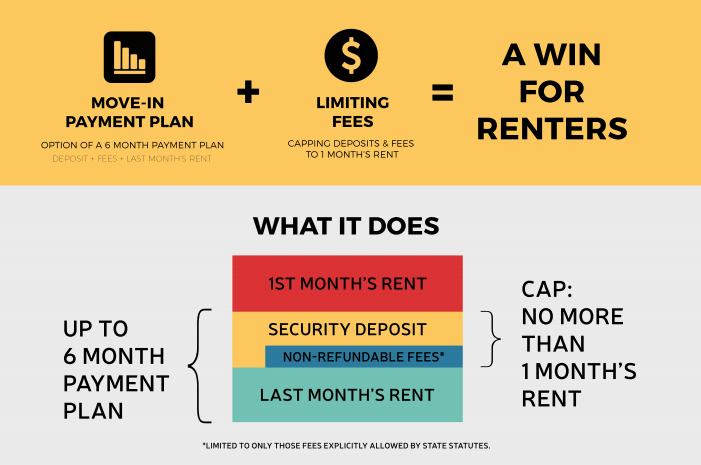

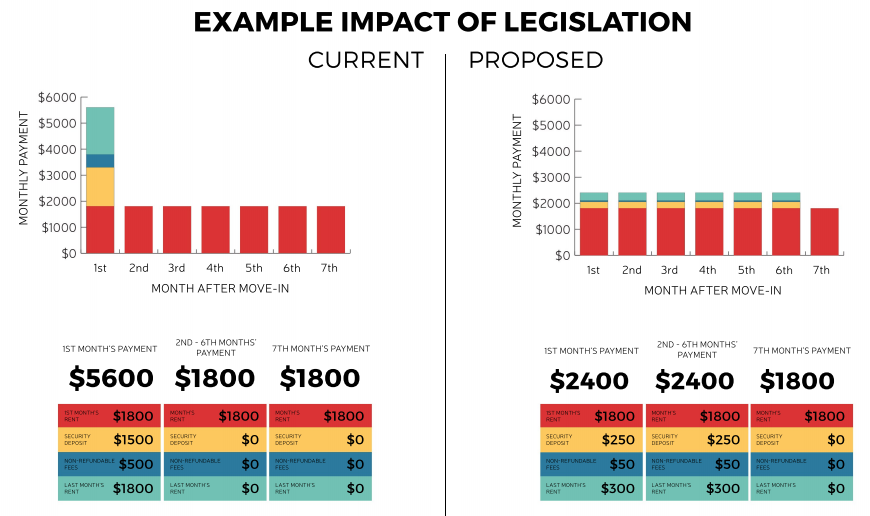

Council Bill 118817, among other things, limits the total amount of non-refundable move in fees that a landlord may charge a tenant to no more than 10% of first month’s rent. It limits the combined total of any security deposit and non-refundable move-in fees to no greater than first month’s rent, and, according to District 3 councilmember and champion of the legislation Kshama Sawant, “most importantly allows tenants to pay a security deposit and last month’s rent on a payment plan” over the course of the first six months of tenancy on a twelve month lease, and the first four months of tenancy on a six month lease.

The legislation was designed to augment the social mobility and financial leverage of over half of our body politic who may view current economic realities in our city as a housing affordability crisis unprecedented in recent memory: renters. It was also introduced to stay the eager hand of an important minority that offers an essential service during what also, simultaneously, may be seen as a revenue growth opportunity unprecedented in recent memory: private housing providers. But now that the bill has become the law of the land, has its defining goal been accomplished? Are landlords required to allow payment plans for both security deposit and last month’s rent to their applicants? No. Because a vast loophole was built into the legislation during the amendment process.

In her defense of referring the bill back to committee during the October meeting, District 5 Councilmember Debora Juarez expressed her hope that the city could “make an incredible law…that we can implement, that doesn’t sit on the shelf somewhere and that a year from now we’re not fighting over definitions…” In that same defense she asked, in passing, “what is the effect of holding fees that are typically collected at the time of application before a lease agreement is written?”

During discussions about proposed amendments to the council bill at the special meeting of the Energy and Environment Committee on November 22nd, the same topic of “holding fees” was briefly addressed in the following exchange on the topic of Amendment 1, which clarified the definitions of both “non-refundable move-in fees” and “security deposit” to specifically exclude “payment of a reservation fee authorized by RCW 59.18.253(3).”

District 1 Councilmember Lisa Herbold inquired, “How would the fact that we’re not counting the holding fee impact implementation of this law?”

“This amendment was made to be consistent with state law that allows for this type of fee to be collected,” replied Aly Pennucci from Council Central Staff. Pennucci also provided an example of how this would work in practice, for a unit that costs $1,200 a month: “You’re signing a year lease. Your payment plan for your security deposit would be $200 a month. You paid a $500 reservation fee. The landlord could either take that $500 and just deduct it off your first month’s rent, or they could say your first installment plan is covered and the remaining $300 would be applied to first month’s rent.”

Without further discussion or inquiry, Councilmember Sawant herself moved to pass the amendment and Councilmember Herbold seconded. It passed.

But if you follow the rabbit all the way down the hole, this hypothetical example is found to be lacking in many regards. According to the Revised Code of Washington (RCW) 59.18.253, a landlord may indeed require a reservation fee, and “the landlord must credit the amount of the fee or deposit to the tenant’s first month’s rent or to the tenant’s security deposit.” This is true, but what is also true is that there is no explicit limit to the amount that may comprise that fee. If you employ the inclusive rather than the exclusive sense of the conjunctive ‘or’ in this clause (first month’s rent ‘or’ security deposit), as Pennucci’s example suggests you can, a case may be made that the implicit limit on what a holding fee can be is up to the total amount of the security deposit and up to the total amount of first month’s rent.

This means that a landlord may indeed collect up to two month’s rent upfront, often well in advance of move-in day, while the applicant is still paying rent for their current apartment. Thus avoiding the requirement that they create a payment plan for their prospective tenant. And if they heed the advice of the Rental Housing Association of Washington, they will. And they are. The customary charges of two month’s rent can be collected in advance without a payment plan, so long as the monies collected are called a reservation fee, rather than a security deposit. But when a tenant moves in, these funds can actually become nothing other than a security deposit or rent. If a landlord feels like making a pretty safe bet that the applicant they are dealing with is not aware of their rights to a payment plan (since the landlord is not required to disclose that right until after a lease has already been signed, by delivering the tenant a copy of the Seattle Landlord Tenant Law), they can even charge last month’s rent as well without offering a payment plan.

One month separates Councilmember Juarez’s question about the “effect of holding fees” during the October vote to send the bill back to committee and Councilmember Herbold’s question during the November special session about the holding fee’s impact on the “implementation of this law”. Juarez’s question could have been answered, and Herbold’s question would never have to have been asked, if that month was spent putting a cap on holding fees, rather than specifically excluding them from certain parts of the legislation. Moreover, Juarez’s wish for an enforceable law free of semantic conflict would have been granted, and what Councilmember Sawant described as the most important part of the legislation would have remained intact.

Putting a cap on holding fees rather than exempting them would not have been inconsistent with state law, it would just further define, clarify, and set limits for the City of Seattle. For example: under state law, there is no limit on what a landlord may charge for a security deposit, but Council Bill 118817 does just that. The two laws are nested, not inconsistent. No RCW sets a limit on non-refundable fees, but Council Bill 118817 does. Again, not inconsistent, just more detailed, in an effort to address a known issue in the municipality.

If any citizen, councilmember, landlord, or lobbyist needs to know where to turn for guidance on how to remain consistent with the spirit of this particular state law, they need look no further than House Bill 1336. You know the one. The one that the State House of Representatives passed unanimously on March 14th, 1991 and the State Senate passed with a 43 to 6 majority a month later. The one whose stated goal was to address the issue of prohibitive waitlist fees and application costs in Washington. The one that became RCW 59.18.253, the very law over whose definitions we are still fighting 26 years later. The very law that the housing lobby and their stakeholder members cite to bypass the security deposit requirement. The legislative findings that serve as the preamble to House Bill 1336 are copied below for posterity.

”The legislature finds that tenant application fees often have the effect of excluding low-income people from applying for housing because many low-income people cannot afford these fees in addition to the rent and other deposits which may be required. The legislature further finds that application fees are frequently not returned to unsuccessful applicants for housing, which creates a hardship on low-income people. The legislature therefore finds and declares that it is the policy of the state that certain tenant application fees should be prohibited and guidelines should be established for the imposition of other tenant application fees.”

It is unclear if this loophole was the product of compromise, sleight of hand, or simple oversight. Little exists on the public record to make any of these claims with certainty. But Seattle is now two thirds of the way into the 180-day review period for the implementation of this law, and perhaps the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (the body charged with enforcing this law) still has time to address the inconsistencies between the law as intended, the law as written, and the law as practiced.

Until then, savvy renters may hope that their future landlord is unaware of his or her right to circumvent the creation of a payment plan for security deposits by renaming it, and savvy landlords can cross their fingers that their applicants have missed a local news cycle, or (if they are coming in from another city, state, or country) haven’t gone digging around in the minutiae of municipal law to arm themselves with the ability to ask for one. One may only hope that both pitchfork and resistance fist be dropped to shake hands in the spirit of transparency, that some day soon both tenant and landlord might meet each other under mutually understood terms. Until then, it seems we are fighting over definitions.

Curtis Little is a freelance editor, translator, and writer who lives and operates in the University District of Seattle. A northwest native, he hails from Anacortes, Washington. He also works in the property management industry and maintains a deep and abiding respect for each person he is lucky enough to encounter during the sometimes daunting performance of renting an apartment in the city of Seattle.