Boosters of the International District have put a lot of work into branding the district’s distinct Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese cultural identities. Over the years, the neighborhood have used various strategies to add cultural character such as wall murals, artistic wraps on utility boxes, stylized light poles, ornamental statues on street poles, and even a Chinatown gate.

Developing Cultural Identity Through Street Signs

In the late 2000s, the Chinatown and Japantown communities wanted to visually communicate their languages through street signs–languages that can still be seen in those precincts today. Together, the communities petitioned the City to evaluate a program that would involve installation of bilingual street signs.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) began a process in 2011 to develop specific policies and designs for bilingual street signs since the City didn’t have a standard for them–a fact that shouldn’t come as a surprise since the City has no record of any bilingual street signs prior to the communities’ request. While other cities across the country had instituted bilingual street signs, SDOT couldn’t just copy what was out there because the federally-mandated MUCTD (Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices) standards had been updated. SDOT carefully designed signs that would be clearly identifiable from standard City street signs. Instead of signs with a solid green background, SDOT’s bilingual street signs have two background colors: green (English) and brown (non-English). Naturally, the signs are larger in size than a standard street sign to fit the added text.

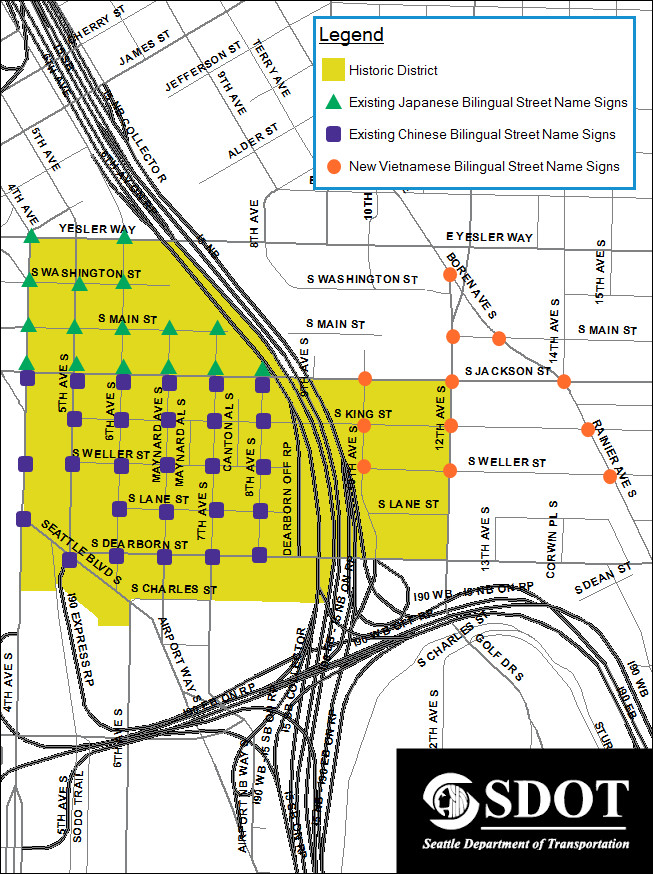

Translation efforts for the signs were led by the Chinatown-International District Business Improvement Area (CIDBIA) to ensure that bilingual signs accurately reflected the communities’ interpretation of the street names. In 2012, SDOT installed the signs at 27 Chinatown intersection and 16 Japantown intersections. Street crews wrapped up installation just in time for the 2012 Dragon Fest. Eventually, boosters of Little Saigon decided that they also wanted to participate in the program. SDOT worked with the Seattle Chinatown International District Preservation and Development Authority (SCIDPDA) to translate street names into Vietnamese for the Little Saigon community. This year, SDOT crews installed bilingual street signs at 12 Little Saigon intersections and again finished up work before the Celebrate Little Saigon festival in August.

The Historic Connection

For more than a century, Chinese- and Japanese*-Americans have inhabited what has become known as the International District near Jackson Street between Fourth Avenue and I-5, but that wasn’t the first home of Seattle’s Chinese population.

The Chinese community was repeatedly pushed out of their settled neighborhoods. First from the waterfront near Pioneer Square, the home of what were largely dockworkers, after the Seattle Riot of 1866. The riot broke out over economic strife and racist furor against Seattle’s Chinese population. Eventually, the Chinese community again settled closer to the heart of Pioneer Square at Washington Street and Second Avenue, but as land values skyrocketed during the early boom years of the 20th century, the community found itself in search of a new home. Many within the Chinese community headed a few block south and east toward King Street and Fifth Avenue.

Meanwhile, Seattle’s Japanese community settled at what is the east end of today’s Chinatown (Dearborn Street near Eighth Avenue) in the late 19th century. By the 1920s, the Japanese community had established a district centered on Main Street stretching from Fourth Avenue to Seventh Avenue, the area largely considered Japantown today. And after the fall of Saigon, waves of Vietnamese immigrants settled in the area east of I-5 creating a new identifiable Asian-American district.

Bilingual streets signs like those now found in the International District are a modest investment by the City (ranging from $500 to $1,000 per sign), but they are an important tool to celebrate and cherish living cultures in Seattle. And as new development takes hold bringing with it new residents to the International District, bilingual signs will continue to be a useful cultural preservation tool.

*Excepting the period of internment of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps during World War II.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.