In approving a final $15.5 billion two-year transportation budget late last week, the Washington State Legislature made a choice to get a handful of highway megaprojects across the finish line ahead of a number of other state priorities, including basic highway maintenance and preservation.

In facing a $1 billion budget shortfall that was set to snowball to at least $7.6 billion over six years, lawmakers spent the session weighing a number of paths forward, including raising taxes and deferring long-promised highway capacity projects. For a brief moment, it looked like the legislature would finally have to grapple with more than two decades of decisions to prioritize highway-building, a fact that has led to a 2024 transportation budget where 12% of funding went toward debt service, leveraged to build past projects.

But in the end, getting projects like the extension of US 395 in Spokane (dubbed the North Spokane Corridor), the extension of SR 509 and 167 in North Pierce and South King Counties (the so-called Puget Sound Gateway), Clark County’s I-5 Bridge Replacement, and I-405 and I-90 widening moving forward proved to be the legislature’s top priority.

Those widening projects are all but certain to push the state further from its own climate goals, encourage more driving and increased suburban sprawl. At the same time, the choice to prioritize new infrastructure over existing means that the state’s highways, bridges, and other facilities will continue to fall into disrepair, maintaining the infamous “glide path to failure” highlighted by former state transportation secretary Roger Millar.

$3.2 billion in new revenue over 6 years

The newly approved budget includes a broad array of new taxes and fees, including a six-cent increase to the state gas tax, a luxury vehicle tax, increased vehicle registration fees and an increase to the state sales and use tax on vehicles. Fees for driver’s licenses are set to increase, as well as taxes on rental cars. Ferry riders will also see fee increases, as the 50-cent capital vessel surcharge doubles this fall and riders are also charged to recoup credit card fees.

Some revenue options were left on the table. An earlier proposal included in the Senate’s transportation budget to tax e-bikes an additional 10% in sales tax and to charge public transit vehicles additional registration fees was dropped, but the budget does move forward with removing the existing exemption for transit vehicles on the state’s toll roads.

On top of that, the legislature will start diverting 1% of the state’s 6.5% sales tax into the transportation budget, starting in 2027, a move that will yield around $300 million per year — funds that future legislatures could have utilized to backfill cuts to schools, health care, and other state services.

But many of those new revenue sources only needed to be tapped into in order to keep the highway megaprojects moving. The $1.4 billion yielded by the 6-cent gas tax increase, for example, almost exactly matches the amount of funding needed to complete the rest of the $2.8 billion Puget Sound Gateway project.

Out of the $11.8 billion two-year budget for the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), 36% of funds are set to be spent on highway improvements, most of which are geared toward expanding capacity. The budget also increases funding for court-ordered fish passage barrier removal — in compliance with a federal consent decree — adding another 9%. But without the highway projects, the budget crisis largely would have ceased to exist.

Even with all of those new funds, the budget still puts a number of prized highway projects on ice, delaying them into future years. A widening of SR 18 in Southeast King County has been pushed out, along with a widening of SR 3 in Kitsap County near Gorst, and a long-planned replacement and expansion of the US 2 trestle in Snohomish County.

Bipartisan agreement on highway capacity

Unlike the state’s $78 billion operating budget, negotiated and approved almost entirely among Democrats, lawmakers touted the transportation budget as a point of broader unity. Even as the Trump Administration takes every opportunity on the table to slash transit and other climate initiatives and prioritize automobile capacity and dependency, this bipartisan agreement at the state level didn’t seems to cause any introspection for Democrats.

“I’m proud that [the budget] reflects our bipartisan commitment as a Senate to invest in our infrastructure all around our state,” Senate Transportation Committee chair Marko Liias (D-21st, Edmonds) said Sunday. “We’re keeping our promises on the core projects that Washingtonians, in some cases, are watching under construction right now. We will finish the job on the North Spokane Corridor, on the Gateway, on 520, on other corridors that are really important.”

“There are compromises that have to be made, but I feel very good that we are moving forward on the megaprojects,” Senator Curtis King (R-14th, Yakima), the top GOP member on the transportation committee, said. Diverting a portion of the sales tax has been a longtime priority for King, and one he was finally able to make headway on this year with the help of Senate and House Democrats. King said he is also focused on getting those other deferred projects from the 2022 Move Ahead Washington transportation package, like SR 18, across the finish line in future years.

“I can assure people that those projects that were in Move Ahead might have been moved out a little bit, but our efforts are going to be to see that they are covered as well,” King said.

The cost of deferring maintenance

With funding for new projects maintained, the amount of funding WSDOT has to allocate to the preservation and maintenance of existing infrastructure will remain “essentially unchanged” over the next two years, though the legislature has signaled an intent to add $300 million (around 2.5% more in the context of WSDOT’s budget) over the 2027-2029 biennium. That means the state’s maintenance backlog will continue to only see around half of the investment needed to keep pace with needs.

“WSDOT is facing a steep, uphill battle as rising costs and budget constraints continue to hamper its ability to maintain Washington’s highways,” WSDOT’s accountability webpage, the Gray Notebook states. “Despite recent, significant investments from the 2022 Move Ahead Washington package, the agency has struggled in the 2023-2025 biennium, losing over $37 million in purchasing power due to inflation while attempting to address increasing demand for repairs.”

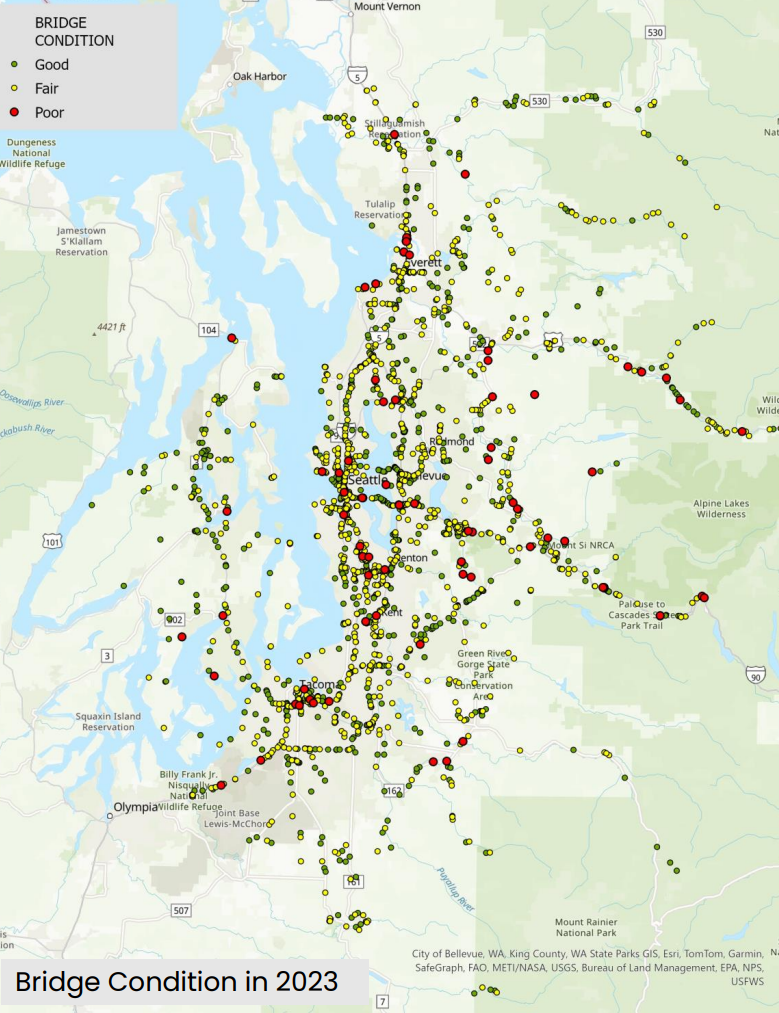

The failure of the 103-year-old Carbon River bridge into Mount Rainier National Park earlier this year is a very concrete example of the impacts of that lack of investment, and almost certainly isn’t an outlier. Across the four-county Central Puget Sound Region, the number of bridges in “poor” condition increased from 69 to 88 between 2020 and 2023, with 49 of those bridges owned by the state, according to data from the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC).

Leadership at WSDOT have been sounding the alarm over this lack of maintenance for years, with former WSDOT Secretary Roger Millar, who left the job in January, offering a dire warning on the state of the transportation system on the way out the door. His predecessor, Julie Meredith, has picked up right where he left off, telling the Puget Sound Regional Council earlier this year how swiftly the state needs to turn its attention away from shiny new infrastructure and toward maintaining what exists now.

“Over the last 25 years, I’ve worked on capital delivery, and you’ll hear me say, we’re really fortunate to have worked on $16 billion of infrastructure, really important infrastructure, but that same level of investment has not been made in our maintenance and preservation program,” Meredith said. “We need to invest in our maintenance and preservation and it has been something that hasn’t been invested in, to keep up to a state of good repair.”

The state’s maintenance backlog is separate from that of the county and city road network, which in some ways is in even more dire straits given the lack of revenue tools available to local governments. Throughout the four-county region, the maintenance backlog for local road maintenance increased from $6.1 billion from $9.2 billion between 2021 and 2025, a full 50% increase in just four years, per PSRC.

A few bright spots in the budget for transit and safety

Though the overall structure of the budget doesn’t move the state in the right direction, it does have some wins for walking, biking, and transit advocates. Local grants for pedestrian and bicycle safety, including biannual Safe Route to School grants, have increased by nearly 70% to $165 million. This increase will be incredibly important in the wake of impending federal cuts to federal walking and biking funds over the next three years or more.

Washington’s transit agencies will receive a $9 million to fund additional transit service around the state in advance of the 2026 FIFA World Cup, 40% of which will go to King County Metro. With the City of Seattle doing very little in infrastructure upgrades to prepare for this major event, a cash infusion to run additional transit service will be a big way to keep people moving.

Supplemental funding for Kitsap Transit’s fast ferry between Bremerton and Seattle, maintained in the House budget, did not make it into the final budget sent to the Governor, meaning that additional trips including the entirety of Saturday service through the off season is poised to be eliminated if another source of funding isn’t found. The budget does include some funding for King County’s water taxi between Vashon and Downtown Seattle, though exact service levels aren’t certain.

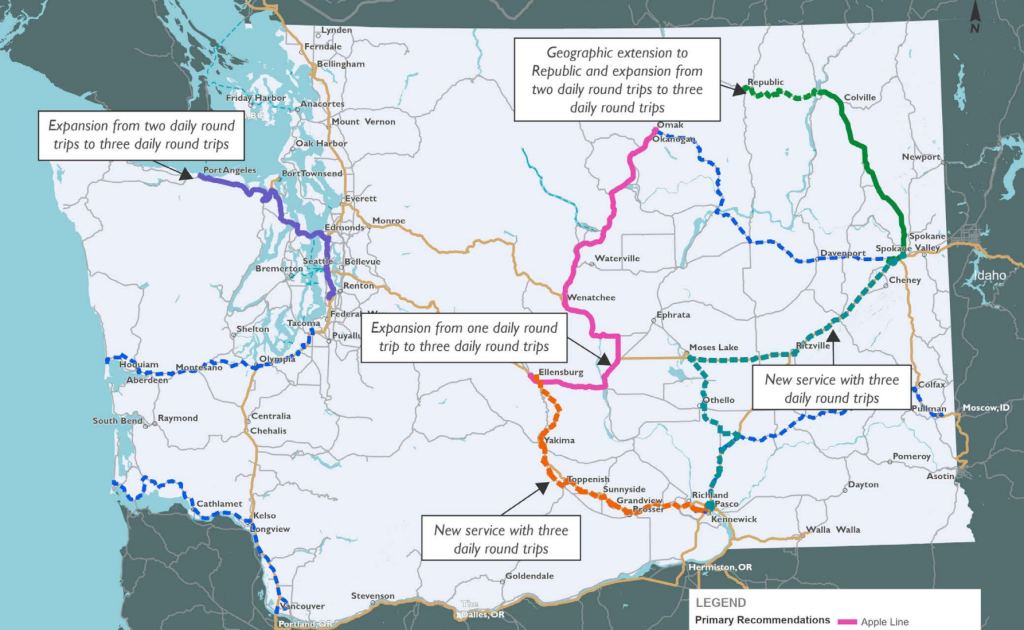

An additional $5 million will go toward expansion of the state intercity bus network, also in advance of the World Cup. This amount is around half of the amount needed to implement the top recommendations of a 2024 report breaking down prime expansion opportunities for the bus network, but those upgrades will make Washington’s lifeline bus routes much more accessible to many.

An even bigger bright spot is a $100 million allocation for the state’s most dangerous state highway corridors. That funding is not allocated until 2027, and represents just one third of the amount initially requested by Secretary Millar last year to start to make changes to Washington’s “stroads” — corridors that are trying to be streets and roads at the same time, and failing at both. But if it’s maintained in two years, it would represent a big step forward for a state that has largely left its most deadly highways untouched even as it’s poured billions into new ones.

Deferring maintenance work to focus on highway megaprojects at this point has become de rigueur in Olympia. While there are no signs of that trend changing any time soon, at a certain point that lack of investment will start to translate into tough choices for lawmakers. For now, the era of megaprojects continues.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.