A draft mandatory inclusionary zoning policy would encourage smaller, more affordable homes while requiring larger new homes to include affordable units or pay a fee.

Like other cities across the state, Kenmore is updating its development codes to comply with Washington’s Middle Housing and accessory dwelling unit (ADU) laws intended to address the housing affordability crisis. Most of Kenmore’s proposed changes will meet the minimum requirements of the law.

But Kenmore may adopt an inclusionary zoning (IZ) policy alongside state mandates that would require developers to offer 10% of units as affordable or pay a fee-in-lieu. A Regional Coalition for Housing (ARCH) recommended the IZ plan to Kenmore, as the influential Eastside organization has done in other cities.

At the May 12 meeting, the city council told staff to rewrite a key provision in the Planning Commission’s recommended IZ proposal — instead of a “project-size” exemption threshold, the council wants to exempt developments based on “unit-size.”

The difference matters.

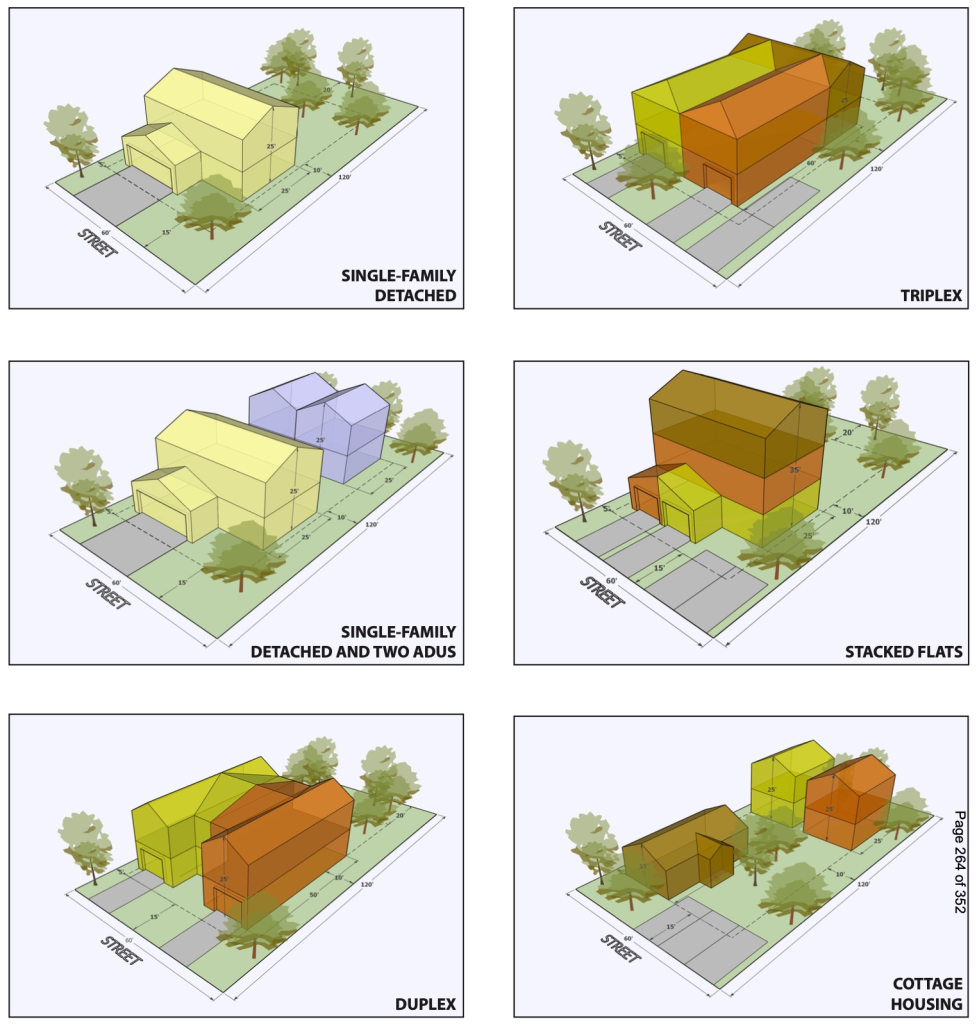

The “project-size” threshold recommendation from the Planning Commission would have exempted projects with less than four units (such as single-family homes, duplexes, and triplexes) from the mandate. That could raise the cost of multifamily projects with more than four units, potentially encouraging developers to build larger, more expensive homes. Because there would be no funding or bonuses attached, the plan could stifle middle housing projects with four or more units.

In contrast, the “unit-size” threshold policy the council preferred would exempt smaller, typically more affordable multifamily homes from the mandate, while larger, more expensive homes would pay the fee or offer an affordable unit. New homes smaller than 1,750 square feet would be exempt from the IZ mandate.

Kenmore’s Mayor Nigel Herbig supported the “unit-size” threshold, saying it “both penalizes what we already have too much of, which is large single-family houses, and incentivizes what we’re looking for, which is smaller, more affordable units.”

Smaller homes tend to be more affordable than larger homes. Last year, the median size of a new condo in Kenmore was 1,487 square feet and sold for $712,353, according to ARCH data. In contrast, new single-family homes in Kenmore list for over $1.5 million and typically are larger than 3,000 square feet.

The Planning Commission approved the “project-size” threshold recommendations by a 4-3 vote. The dissenting commissioners wrote a “minority report” arguing the proposed exemption for projects with three or fewer units could unintentionally incentivize larger, more expensive units and continue a common development pattern of large single-family homes, limiting production of more affordable units.

Under the Kenmore IZ proposal, 10% of new units would need to be offered as affordable. An owner-occupied home must be affordable for people earning 80% of the area median income (AMI). Rental units would need to be affordable to people earning less than 50% of the AMI. Developers could pay a fee-in-lieu for fractional units or to avoid offering the affordable homes.

ARCH recommended the city set a fee-in-lieu of $6 per square foot, and said the fee would be modest compared to other ARCH cities such as Kirkland and Redmond. Sammamish recently adopted a 10% IZ requirement similar to the one under consideration in Kenmore.

Proceeds from the fees-in-lieu would go into Kenmore’s fund for affordable housing, and could be used by groups like ARCH to pay for regional housing needs.

Kenmore is a member of ARCH, a partnership of East King County cities working to preserve and increase housing for low- and moderate-income households. ARCH coordinates resources, shares staff and technical resources, and helps administer programs. ARCH is helping Kenmore draft their ADU and Middle Housing code amendments, and provided the city with financial modeling and feasibility analysis.

While the funds might be useful for building new affordable housing, Mayor Herbig had reservations. “I’m concerned about adding additional costs. I would much rather […] find additional sources of revenue for housing. It’s something I really want us to figure out. I’m not sure if taxing housing to incentivize housing, or taxing housing to fund other housing. […] There just seems something a little almost perverse about it.”

Kenmore currently has a voluntary Residential Density Incentive program, which offers incentives, such as bonus units, for developers who build affordable housing units. The city also offers tax breaks for affordable housing through an existing Multi-Family Housing Property Tax Exemption (MFTE) program, but that MFTE program does not apply to the neighborhoods where the proposed IZ would be implemented.

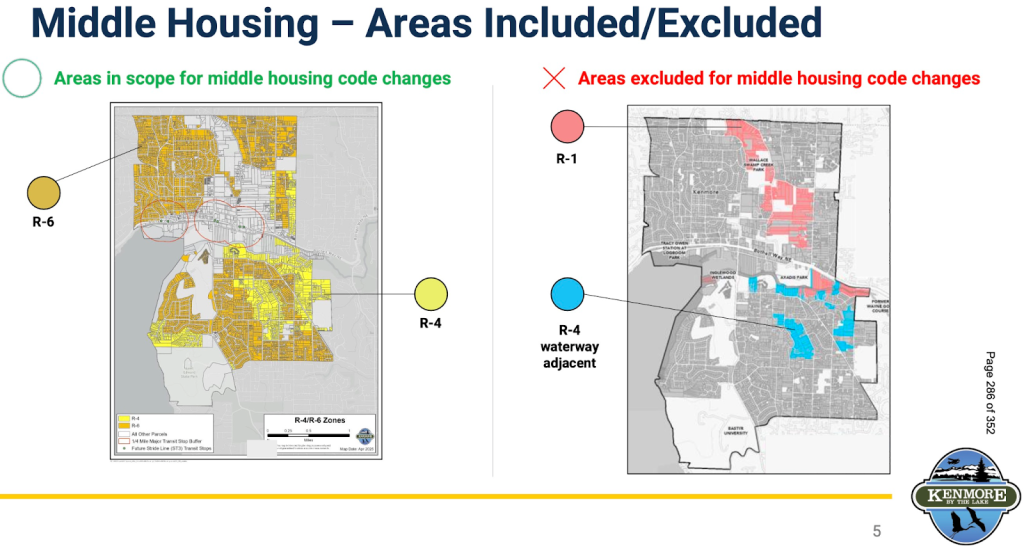

Kenmore’s proposed IZ policy would apply to the city’s R-4 and R-6 zones – its largest, traditionally residential neighborhoods. These formerly single-family-only zones will be upzoned to follow the state’s Middle Housing laws. The city plans to exempt properties along Swamp Creek and the Sammamish River and tributaries from the middle housing rezone, which represents about 14% of total single-family lots. State law allows cities to exclude up to 25% of lots in single-family zones from middle housing requirements.

Kenmore has until June 30 to adopt the state Middle Housing and ADU code changes. Formerly single-family zones will permit Middle Housing home types such as duplexes, townhouses, and cottage housing. At least two homes per lot, and up to four units if at least one is affordable, will be permitted. Within a quarter mile of a major transit stop, the allowed density increases to four units, with up to six units allowed if one is affordable. Up to two ADUs per lot will be permitted, and parking requirements will be reduced.

Those changes will increase the development capacity (and land value) of properties within the upzoned areas. According to ARCH and city staff, implementing IZ concurrently allows the city to “capture” a portion of that increased land value created by the upzoning to help fund affordable housing, without necessarily causing undue financial pain to developers. ARCH said their analysis suggests the plan would leave a net gain and warned the city that trying to adopt new IZ requirements later, after the capacity increase is already in effect, could face legal challenges.

However, many builders view mandatory inclusionary zoning requirements differently, arguing such policies raise the cost of homebuilding and the price of housing, especially at high percentages and deep affordability levels. The Master Builders Association warned the planning commission their draft IZ policies could unintentionally hinder housing production.

Small-scale builders also argue their margins are smaller and access to capital more limited, making it harder to absorb IZ costs in middle housing projects. Caitlin Sullivan, a Kenmore real estate investor focused on middle housing infill development, criticized ARCH’s research. “When the ARCH inclusionary zoning proposal was first introduced, it didn’t look right. […] We cannot risk adding a fee onto small developments, especially when we’re doing it on bad data.”

Sullivan urged the city council to adopt a square footage exemption. “We have enough large single-family homes which decrease affordability in our community, and we need to start rebalancing the scales,” she said.

A public hearing on the draft rules is planned for June 9, with a final council vote anticipated on June 23. Kenmore has until June 30 to adopt development code changes, or the state model ordinance will take effect.

This artile is an expanded version of a piece that first appeared on Oliver J. Moffat’s personal site.

Oliver J. Moffat is a cyclist, transit enthusiast, pedestrian maximalist, and an amateur journalist covering hyperlocal news in North King County. He’s lived in Shoreline’s North City neighborhood since 2006 after being priced out of Seattle and daydreams of abundant housing and walkable neighborhoods. A recovering tech-bro, Oliver now volunteers as an urban forest restoration steward, digging up noxious weeds.