Social housing backers hope to meet an ambitious green housing standard called “Passive House” while maintaining affordability.

Despite leading the curve on many metrics among U.S. cities, Seattle still lags behind countless cities in Europe and Asia in key areas like affordability, climate preparedness, and emissions reductions. While many other American cities look to us for examples on how they could smarten their city planning and design, the individuals and organizations working to steer Seattle toward a brighter future have their gazes fixed firmly on the examples of superstar cities like Vienna.

The Austrian capital has been a leader in public housing policies since the early 20th century. House Our Neighbors, the nonprofit that championed social housing in Seattle, hopes that the newly established authority can take inspiration from the Viennese as it seeks to develop buildings that are affordable while meeting the strictest of green building standards, called “passive house.”

Achieving these standards would ensure that apartments use a minimal amount of energy and are well-prepared to withstand the onslaughts of climate change, something that can’t be said for the overwhelming majority of Seattle’s building stock.

The ambition for super efficient buildings that adhere to top tier standards for green design isn’t an aspiration held by a minority of members on the board of the Seattle Social Housing Developer; rather, passive house is a requirement for the authority, embedded in the organization’s charter. The eighth principle that the authority must follow under the second section of the charter’s second article states: “New developments must meet green building and passive house Standards.”

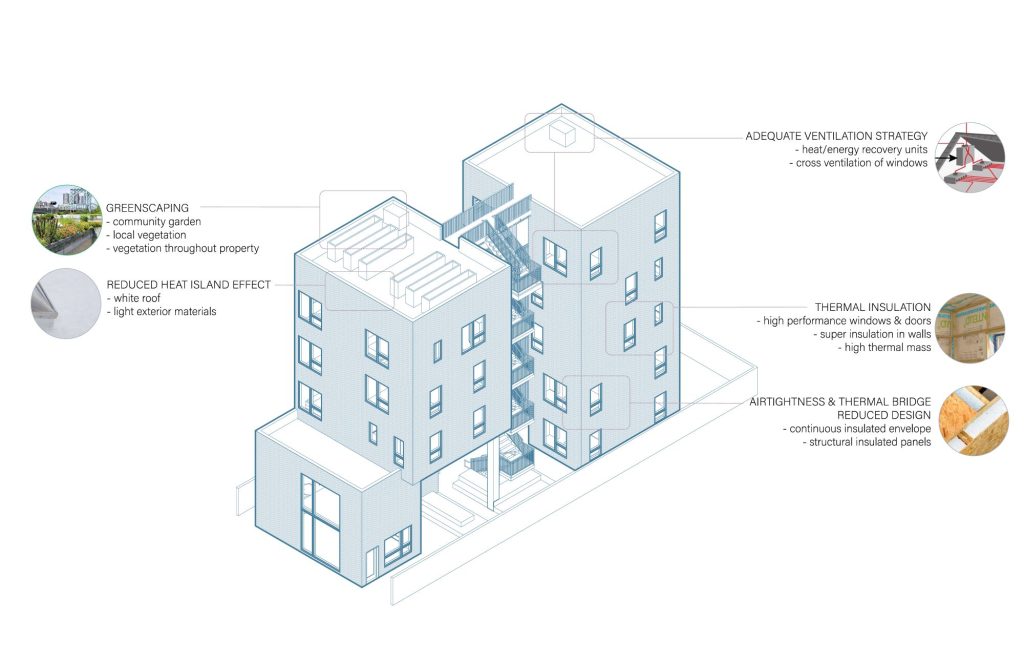

Passive house encompasses a set of high efficiency building practices that aim to create buildings that are as energy efficient as possible while ensuring comfortable conditions for residents. This is primarily achieved through four main principles: air-tight designs, continuous insulation, heat-exchanging ventilation, and high-performing windows. Altogether, these principles aim to limit the heating and cooling required, often the greatest energy drain in any building.

These standards were first developed in Germany in 1996 and have become increasingly adopted throughout Europe. In the United States, however, these standards have only stumbled and staggered onto the scene over the last decade and a half. Today, across the country, many professionals in architecture, urban design, and building trades remain either unaware of or wary about passive house, except for in certain states like Massachusetts and Pennsylvania where policies either mandate or incentivize its adoption.

House Our Neighbors nestled the requirement for this standard into the charter adopted under the 2023 ballot initiative at the suggestion of Michael Eliason, an architect and founder of the firm Larch Lab. Eliason first learned of passive house and related practices that prioritize sustainability and public health through urban design during his time working in Germany. Through those experiences, he was “exposed to a radically different way of how we design and build housing,” Eliason told The Urbanist.

So when Tiffani McCoy, co-executive director of House Our Neighbors, contacted him to solicit his opinion on what green standard to include in the charter, he had no doubt which would be best.

“I don’t think there’s another green building standard that approaches climate adaptation and public health to the degree that passive house does,” said Eliason.

The approach ensures that the building comes together as a comprehensive system that can easily endure temperature extremes on either end of the thermometer while keeping indoor spaces comfortable, with minimal need to warm or cool the air and providing a constant supply of fresh air that’s kept crisp and clean even on days when wildfire smoke infiltrates city spaces, a health hazard that increases in frequency and severity each year. These boons are inherent to any building that receives a passive house certification.

One of the ideas central to passive building principles is continuous insulation. “It’s like putting on a sweater over your whole body,” described Greta Tjelveit, a building science consultant and current board president of the professional association Passive House Northwest.

Most buildings rely solely on cavity insulation, which fills the gap between the structural beams in the wall. While this can provide a decent barrier, it often leaves the studs themselves in contact with both the exterior facade and the inside wall, affording a bridge that heat can use to worm its way through. Continuous insulation provides an additional layer of wrap around the exterior of the building between framing and facade to, as Tjeltveit said, “get that sweater over it.”

In addition to this strong thermal barrier, passive buildings also emphasize airtightness to eliminate another pathway for outdoor temperatures to influence those inside. On its own, however, this airtight barrier could cause the building to get quite stuffy, which is why the standards also require constant ventilation that cycles air from indoor to out. This ventilation also includes devices that exchange heat, filter air, and capture moisture.

By exchanging heat, the system can capture all the warmth that tends to pool in kitchens and bathrooms and, in the winter, redistribute that throughout the building to other rooms that need to be heated. It can work in reverse as well: capturing the chill from already-cooled air to help pre-treat ambient air to limit how much conditioning is required.

“It works in all seasons,” said Mike Fowler, an architect and Passive House Northwest board member. But, in Seattle, it’s most effective in winter, Fowler added, “because we typically have a longer heating season than we do a cooling season.” Mithun, the firm where Fowler works, has designed passive house projects.

The filtration, naturally, helps to prevent dust, smoke, exhaust fumes, and all manner of air pollutants from getting inside. Meanwhile, the moisture recovery system helps moderate indoor humidity, which can ultimately prevent mold from forming. “The air that you’re breathing is far superior than the status quo development,” Eliason said.

The requirement for high-performance windows also helps improve the quality of life for residents as well. Though the push for triple-pane windows within the standard is mostly about insulation, it further dampens sounds from the streets. Despite Seattle’s numerous public transit improvements, it remains a car-dominated city, and is burdened with all the air and noise pollution (and concomitant health issues) those vehicles bring. As such, triple-pane windows are of pronounced importance.

Of course, with all the benefits that passive house standards can bring, it’s natural to wonder whether or not it can be done affordably. “If you spend more up front,” said Al Levine, a former executive with the Seattle Housing Authority, in a February interview with Grist, “you have to recoup that in rent.”

But Eliason, Tjeltveit, and Fowler all argue that passive house can be achieved without paying a large premium, and that concerns about extra costs come from a lack of familiarity with the standards. They point to ample examples to support their argument, such as Pennsylvania. In 2016, the Keystone State was among the first in the nation to incentivize passive house for affordable housing projects in the state by giving such projects a boost in their funding projects.

“In the first year of that program,” Fowler said, “the prices were five to seven percent higher for passive house. In year two, they were two or three percent, and then in the third year, they were the same cost as everything else.”

All it took for passive house projects to reach cost parity with status quo developments, as Fowler sees it, was for developers, architects, and contractors to get familiar with the standards. Fowler himself has seen how passive house can even lead to cost savings in certain building systems. For instance, on a project in Atlanta, the overall cost of the building project was just 0.6% greater than it would have been if they had designed to Georgia’s minimum code requirements.

“The biggest thing,” Fowler said, “was that our mechanical systems came in half a million dollars less because we didn’t need these giant pieces of equipment to throw a lot of air conditioning load at it.”

There’s also projects here in Seattle that show that affordable, passive house-certified apartments can be built without exorbitant cost increases. For instance, a three-story, 12-unit apartment building was recently developed by Red Door Sustainable Housing in South Seattle and, in a talk for Passive House Accelerator, Dan Whitmore, one of the firm’s founders, estimated that the cost premium for meeting passive house was likely between just 3% and 4%.

Even with a small, initial upcharge of this kind, the diminished size of mechanical units for heating and cooling translates to reduced operational costs for the building in the long term, both in terms of energy and repairs.

So while it seems distinctly possible for the Seattle Social Housing Developer to reach passive house standards in new projects without jeopardizing its other goals – namely, ensuring affordability for a range of income levels to promote an economically diverse community of residents in its projects – this will likely have to wait. The developer is still waiting for the newly-won funding to arrive since the passage of Proposition 1A earlier this year, which is set to provide more than $50 million annually. Additionally, most of the units that the developer first brings online will come not from new construction, but from the acquisition of existing buildings.

Even once the developer gets its own projects underway, Seattle will have much to do if it wants to emulate the examples of cities like Vienna. McCoy and House Our Neighbors are actively meeting with experts from Urban Innovation Vienna to learn as much as they can about what the Austrian capital has done to become the world’s most livable city. But as one report on the steps Vienna and Singapore have taken over decades to transform their built environments demonstrates, Seattle and its neighbors will have to think far more holistically about how it builds and meets the needs of a fast-growing population in the coming decades if the Emerald City wants to have any hope of replicating Vienna’s greatest successes.

Syris Valentine is a Seattle-based writer and journalist primarily focused on climate solutions, social justice, and the just transition. Their work has appeared in The Atlantic, Grist, High Country News, Scientific American, and elsewhere, and you can follow them @ShaperSyris on social media and through their newsletter, Just Progress.