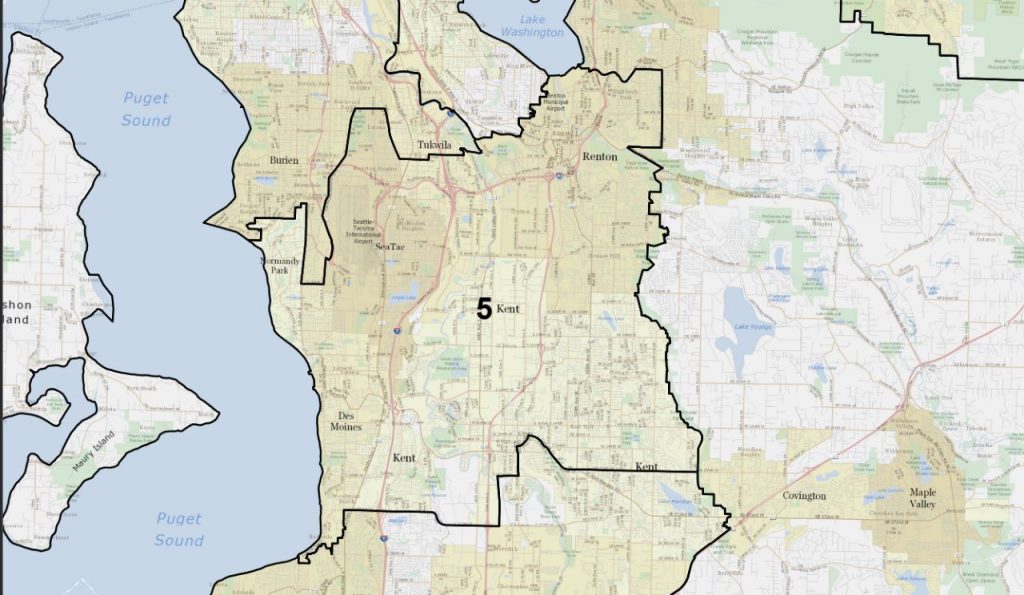

Following a successful primary, where she squeaked ahead of Stranger-endorsed Kim-Khánh Văn to become one of the two challengers for King County Council’s District 5 seat, Steffanie Fain will head into November’s general election to face Peter Kwon, who has held a seat on the SeaTac Council for nearly 10 years. Kwon grabbed 27.7% of the vote, while Fain had 24%.

Fain is an attorney with Coopersmith Law and president of Harborview Medical Center’s Board of Trustees, and earned the Seattle Times endorsement to help propel her through the primary. Though she supports several of the County’s initiatives, including its plan to electrify Metro’s fleet and to create more affordable housing, her chief concern lies with funding — namely, where the money will come from. Generally, she shared a preference to squeeze money out of existing budgets, rather than raise new taxes.

However, as The Urbanist’s interview with Kwon will show later this week, Kwon is even more tax-averse. For either, it could be a tough position to hold as the County navigates a building fiscal storm, with numerous departmental budgets springing holes.

Fain spoke with The Urbanist in August about her positions on pressing issues facing the County, including how to best address Metro’s budget shortfalls and how to best protect the County’s most vulnerable residents from President Donald Trump’s illegal, unconstitutional overreaches.

Metro + Affordable Housing

Though she supports King County’s goal to electrify Metro’s fleet by 2035, Fain worries that the plan may be too ambitious, when factoring in the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic and the unsteady-at-best fiscal situation at the federal level.

“Part of the budget assumes large capital investments,” she said. “We’re going in the right direction — we can still continue to do that — and if there is not enough federal funding coming, because those grants come from the federal government to pay for new fleets, then we have to reprioritize and rethink our plan. So, I want to continue on the path of electrification, but also make sure we’re doing it in a sustainable way to withstand some of the challenges we’re seeing at the federal level.”

Like her opponent Kwon, Fain said that she really couldn’t speak to specific solutions for Metro without diving into the budget. But unlike Kwon, she didn’t take increasing taxes off the table to fill the gap while the council decides what the best routes forward could look like.

Fain also reviewed King County Council Chair Girmay Zahilay’s proposals in his workforce housing initiative, called the Regional Workforce Housing Initiative. Zahilay is running for King County Executive and led the August primary with 44% of the vote.

Council-approved in November 2024, the initiative directs the County Executive to develop a plan to use $1 billion or more of the County’s excess debt capacity to partner with different housing agencies and developers to create permanently rent-restricted, multi-bedroom workforce housing. The plan will include an estimate of how many homes the $1 billion debt financing could create, when paired with rent revenue from the mixed-income buildings — and if this revenue could sustain such a model going forward.

When she spoke with The Urbanist in August, Fain said that she did not feel prepared to talk about either Metro’s budget or the affordable housing plan, though she did note that “there was a lot of information that came out of that, both supporting the proposal, but also identifying some funding concerns.”

When The Urbanist followed up with Fain in September, she said that she had had a moment to review Zahilay’s housing initiative.

“While the report makes clear that rental income alone wouldn’t cover the debt, I see real potential in carefully leveraging bonds and pairing them with new revenue sources to make projects viable,” she said. “I’ll work to ensure we explore this tool carefully so that we can provide more affordable housing in a way that doesn’t put the County at financial risk.”

Fain also highlighted the need to ensure that existing affordable housing in King County is already in good condition, even as the County works to create more. She said that many units have degraded to the point of substandard, unsafe living conditions, which means that they sit vacant — which ultimately narrows the housing market further.

“We can’t afford to let those desperately needed units go unused when so many families are struggling to find a place to live,” Fain said. “We should also remove barriers that drive up the cost of housing, by streamlining permitting, aligning regional planning, and utilizing partnerships with cities, nonprofits, and the private sector to stretch every public dollar further.”

Fain also briefly touched on Metro budgeting, noting that the County’s supplemental budget allocates a little more than $26 million to the transit agency’s safety arm, adding security personnel and operator protections. She said that such investments are “urgently needed — just last week, a person was stabbed aboard a Metro bus in downtown Seattle — which underscores the importance of acting now to keep both riders and workers safe.”

Behind only Florida

Washington state ranks second-worst in the nation for regressive taxes, behind only Florida. A regressive tax is one that takes a proportionally larger amount of low-income individuals’ earnings than from high-income individuals. This is often seen in the form of a flat tax.

“Big picture, yes,” Fain said, when asked whether she wanted to see reforms to change the state’s regressive tax code. “However, my district, District 5, in particular, is very challenged by poverty, taxes, in general, because we traditionally have struggled to receive the same investment in our communities that we feel that we pay into King County.”

Fain said that “there’s a level of distrust that I hear at the doors — a lot of people feeling the squeeze and really wanting to make sure that before we go in for more, we’re investing the dollars that we have in a way that feels measurable.”

In initially answering The Urbanist’s primary election questionnaire, Fain sidestepped directly answering whether she would go to Olympia to lobby for the state to lift the growth rate on property tax collection. When asked again, she underscored what she had been hearing from District 5 residents in the course of door-knocking: Everyone is afraid of being priced out of their homes, particularly elders on fixed incomes and others who do not yet qualify for pensions.

She also iterated that she has been hearing a level of distrust regarding County taxes — “Why do we have to pay more, when we haven’t seen that same level of investment here in South King County?”

“I think there’s work to do to build that trust. I also think that the county [budget] almost doubled in the last five years. And so if we want to raise the property cap, I think that we have to show the voters exactly what we’re going to be spending it on,” Fain said. “I want to make sure that we are responsive to the concerns. I’m not even joking when I say it’s almost every door, every other door that I hit, that was such a major concern for folks — ensuring that we’re being clear on where we’re spending, where we want to spend those dollars and why and what we’ve done to be really effective with the dollars that we do have.”

She also said that nearly everyone who answered her at the door “had a number ready.”

“Everybody — offhand almost — recites the, ‘When I moved in five years ago or when I moved in 10 years ago … this is what I paid and this is what I pay now,’” she said.

Wealth tax

Washington’s lawmakers have for years resisted changing the tax code. Earlier this year, Governor Bob Ferguson torpedoed Washington House Democrats’ proposal that included a wealth tax, as well as a removal of the state’s 1% annual growth cap in property tax collection. House Democrats also proposed adding a surcharge to large companies, and Senate Democrats proposed imposing a new tax on large companies’ payrolls, while nixing some tax breaks.

However, Ferguson entertained the possibility of a wealth tax in a budget that relied on it for only $100 million of the total budget, in order to see whether it could withstand legal challenges — and stand up to political resistance from the wealthy folks facing the tax. Former Governor Jay Inslee encouraged lawmakers to implement a wealth tax, albeit on his way out of office.

Because reliable federal grant money is off the table, and Fain has heard from door-knocking that increasing taxes County-wide would further harm District 5 residents, few options appear available for the County to collect the revenue it needs to fund programs that serve its most vulnerable populations.

But a wealth tax doesn’t appear to be top-of-mind for Fain, either, who said that she has “several process and implementation concerns about proposals for a wealth or corporate tax.”

“First, any wealth or corporate tax would be collected at the state level, so none of those dollars would flow directly into King County’s budget,” she said. “That means even if the state adopted one of these taxes, we couldn’t count on those funds to close any gaps in King County’s budget to address housing, behavioral health, or human services needs.”

“Second,” she continued, “we’ve already already seen progressive revenue measures tied up in lengthy court battles. Building essential services on top of a revenue source that could be struck down or fluctuate dramatically from year to year is risky and it could mean sudden cuts to the very programs our most vulnerable residents rely on.”

Instead, Fain said, the County should continue to work towards “progressive revenue solutions that are legally sound, broad-based, and reliable.” She said that the House and Senate budget proposals earlier in the year were a step in the right direction, and that she would work with legislators and Ferguson’s office in support of fair revenue reforms that would bring in money for investment in South King County.

She also supports efforts to give different counties and municipalities greater local taxing authority. Fain said that she sees this as a way to address critical local issues without being dependent upon state-level decisions.

Trump overreach

Fain said that she would continue to support the King County Prosecutor’s Office in its work to defend the County’s residents against President Donald Trump’s illegal overreach, and noted his attempts to withhold vital grant dollars from human services programs that the County’s most vulnerable rely on.

But Fain again stopped short of another tax of any kind to support these programs. Instead, she pointed to the County’s own stipulations in awarding grant money to both providers and small businesses, and questioned whether they could unintentionally be imposing red tape in ways that stymied potential grantees from working together.

Fain said that ensuring that “grant dollars don’t inadvertently prohibit collaboration [is] my position across the board on all things.”

“So, for example,” she said. “If there are dollars that are, that we put in because we want to help a small business and we say, ‘a business of 15 or fewer [is eligible for this particular grant],’ that doesn’t preclude a small business from working with another small business on certain issues or collaborating together, and that inadvertently prohibits them from getting those grant dollars.”

Fain said that she would like to see the County incentivize collaboration among nonprofits and organizations providing similar services.

“There’s so many amazing small organizations providing services within our many, many diverse communities in District 5, but the infrastructure costs can be really high,” Fain said, listing off different necessary positions within an organization — human resources, billing, legal, and so forth. “I envision a place or a structure where the county could lead on providing the infrastructures so that the groups can focus on the services themselves and reducing their overhead costs. So, things like that where we’re really working together is going to be critical.”

Fain also said that some of the reporting and compliance requirements are burdensome and restrictive on certain providers, particularly those that operate without dedicated administrative staff — and, often, those are the providers that are part of the communities they serve, such as immigrant-and people-of-color-led organizations, family childcare providers, and neighborhood-based service organizations.

“For example, during Covid, many small childcare providers in my district struggled to access stabilization funds because the language barriers and paperwork burden was so intense,” Fain said.

Fain said that she believes the County should support a shared services infrastructure or a centralized support model that provides bookkeeping, human resources, grant administration, and compliance services to community-based organizations.

Regional Homelessness Authority

Fain said that, throughout her campaign, she’s been asked whether she wants to get rid of the King County Regional Homelessness Authority (KCRHA). While she acknowledges the “strong feelings” many have about the agency, and the struggle for it to gain public trust, she doesn’t think it’s time to get rid of it just yet.

Fain thinks that the KCRHA has the potential to provide critical services — but it needs the tools to do it. Having a functional KCRHA is necessary, she said, because, otherwise, municipalities are left to their own devices to figure out how to address homelessness. Most of the time, the result is sweeping people in encampments from one community to another with no durable solutions that address the underlying problems. Homelessness advocates have long called for better solutions, including housing-first initiatives.

Fain said that a functional KCRHA is one that can be more flexible and encourage collaboration with services providers in the field. She sees this as one of the biggest stumbling blocks, and it again comes back to the red tape she said service providers and small businesses encounter in applying for grants.

“I have been trying to meet with as many groups working in this space and in the behavioral health space and I hear a lot of the same issues, which is that inadvertent inability to work together,” Fain said.

For instance, she said, one provider — whom she termed Provider 1 — may be providing services to someone who wants to go to a shelter, but Provider 1 is full. Provider 1 also doesn’t receive KCHRA funding.

Another provider, Provider 2, receives funding from the KCHRA, and has bed space.

However, she said, the restrictions of the KCHRA funding mean that any available beds are reserved for Provider 2’s clients, so the person receiving help from Provider 1 can’t go to Provider 2, if they continue to receive other services from Provider 1.

It’s this situation that Fain said she’s “heard several times defeats the entire purpose of the KCRHA — and so, how can we, as we look at the funding and look at the contracts and the grants, ensure that there’s more overarching collaboration from the top down from the KCRHA that encourages and provides enough flexibility to allow service providers to work.”

“They are all trying to achieve the same goal, which is to get people who currently are without homes into a facility,” she said.

Fain also supports co-responder programs. She said that she has been on a ridealong with first responders and witnessed firsthand how critical it is to have a mental health professional on-scene. She said it’s important to be able to build trust, and not force someone into a shelter or transitional housing without their understanding and consent. Taking time to talk with people to explain the services available, and asking if they want them is far more fruitful, she said — “It shouldn’t just be a, ‘Hey you’re in crisis, now we’re whipping you over here to get services.’”

“So, how can we help and use time to allow them to move with their communities to transitional housing and then eventually permanent, supportive housing and stability?” Fain said. “If we can develop that relationship, that’s a win in my book.”