Significant financial problems at Washington state’s largest transit agency are coming to light, as the King County Council considers its priorities for the 2025 county budget. Without a major change of course, a looming fiscal cliff could significantly impact King County Metro’s ability to maintain service levels, while still achieving the County’s ambitious goal of electrifying its bus fleet by the end of this decade. That’s the conundrum laid out in County Executive Dow Constantine’s budget proposal released last month.

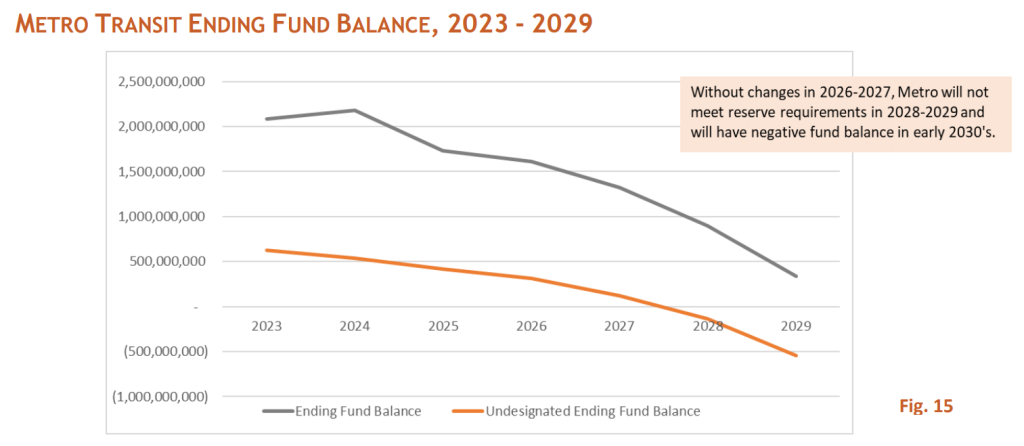

With Metro’s operating expenses continuing to exceed collected revenues and projected to stay that way for the foreseeable future, Metro is expected to be unable to meet its required levels of reserve funds by the 2028-2029 biennium, coming short by $500 million. By the 2030-2031 biennium, Metro could fully exhaust those reserves. The agency’s largest source of revenue, its 0.9% sales tax, has been unable to keep up with growing costs, including higher pay for staff. The agency recently approved a raise for bus operators intended to accelerate recruitment and address the agency’s labor shortage.

Meanwhile, rider fares have essentially become a footnote in the agency’s finances, projected to bring in 7.8% of its total revenue next year. Constantine has worked a fare hike of $0.25 into his budget, bringing the agency’s adult fare to $3 — as he hinted was on the horizon when he pushed for a flat $3 fare at Sound Transit. Even with the fare hike, fare revenue is trending in the wrong direction. (Youth fares would continue to be free, thanks to state Climate Commitment Act funding — though a repeal measure on the ballot could potentially force a tough decision there as well.)

Making matters worse, pandemic-era infusions of cash from the federal government are set to run their course leaving a significant revenue hole.

“We’re hearing a story here about Metro looking at a cliff,” County Councilmember Claudia Balducci said this week during a budget discussion. “It’s coming in the out years, and this is a really important and pivotal time. Big decisions will be coming at us. They don’t [come] with this budget, but I do think we need to set ourselves up for those big decisions, and consider, structurally, what’s happening with Metro, and how do we position ourselves to be able to deliver the service as it as it ramps up. and we continue to see this need.”

This impending shortfall will likely increase the pressure to look for a new source of countywide revenue for transit in King County, likely in the form of a Transportation Benefit District (TBD). In early 2020, as Seattle’s city-specific TBD was set to expire, there was considerable momentum behind the idea of a countywide ballot measure to fund service, but the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic that spring fully deflated that idea and Seattle’s measure was renewed that fall instead, but at a lower rate.

Seattle’s TBD funding will expire in early 2027, with a renewal measure expected to be put forward in 2026. To avoid risk of a gap in funding that forces service cuts, a countywide measure would need to be crafted with a runway that would allow to Seattle to put forth a measure on its own if it fails.

This cliff will also likely prompt a significant look at Metro’s plans for fleet electrification. The 2025 budget includes $448 million for work to put Metro on the path to an all-electric vehicle fleet by 2035, with most of that funding allocated to its first all-electric bus base — South Base Annex — set to open in 2028 with space for 250 electric buses. Future projects like the electrification of Central Base ($176 million), East Base ($148 million) and Ryerson Base ($135 million) are also tabbed in Metro’s capital facilities plan.

Another significant expenditure will be the new electric buses themselves. Metro plans to ramp up purchases of new battery-electric vehicles starting in 2028, purchasing 200 that year and at least 100 every year thereafter, replacing a total of 1,333 coaches (including replacement trolleybuses) by 2035. However, the limitations of current electric bus technology means that Metro would need more vehicles than the present fleet to maintain the same service levels, a fact reinforced by a recent report by the King County Auditor that cast some doubt on the feasibility of the agency’s electrification plans.

“Metro notes that additional buses may be needed to achieve the zero-emission network, depending on technology and layover charging ability,” a staff report provided to the King County Council this week noted.

Overall, Metro’s capital spending is expected to climb to $1.2 billion in 2028-2029 as it works to implement its electrification goals, pushing the agency closer to the fiscal cliff.

Those capital expenditures are likely to come in conflict with the goal of providing more service. Between 2024 and 2027, the number of bus hours Metro provides is set to go up nearly 10%, as the agency gradually restores service to 2019 levels in accordance with the Service Recovery Plan adopted by the County Council.

It’s clear that when it comes to the goals of providing more service, electrifying the fleet, and other priority areas like bus security and facility cleanliness, something needs to give. “Metro’s financial modeling for the next several years shows that these objectives are not all attainable,” Constantine’s budget book notes.

“The policy commitments that we’ve made are going to outpace our projections and our revenue, and so we only have two options when it comes to Metro: we either dial back on our some of our policy commitments, or we find new revenue, otherwise, we’re going to have a Metro department that’s not in good shape in the future,” Councilmember Girmay Zahilay said Tuesday.

The County Council is expected to take a look at Metro’s farebox recovery rate, the percentage of operating revenues covered by passenger fares. The agency’s fund management policies require Metro to collect at least 25% of its operating revenue as fares, a goal which is currently a pipe dream — in 2023, the figure was 8.8%.

If Metro was hitting that 25% minimum, it would be collecting around $150 million more in revenue every year, but so far there are no indications that county leaders are interested in implementing policies to increase that number. Instead, the County seems poised to lower the floor to 10%, a move that mirrors one made by Sound Transit earlier this year.

Currently, 53% of the revenue from fares at Metro comes from ORCA Business Passport accounts, which are paid for by employers. But those riders only account for around a quarter of Metro’s boardings.

“We’re sort of balancing our fare recovery on the backs of this employer program, when our ridership continues to shift from commuters to all day, which is part of the overarching structural problem,” Balducci said Tuesday. “But if we don’t have the cash to operate our service, what’s our plan to address it that will come to head in the next budget? How do we afford this?”

Metro’s financial picture is just one aspect of a larger and more immediate budget crisis King County is facing, with a projected $150 million deficit in the county’s General Fund by next year.

“The revenue system is broken and the crisis is one year away,” Constantine’s 2025 budget summary states, noting how severely the state’s limitations on property tax increases over 1% have impacted the county as inflation has significantly outpaced that cap. “In 2023, the County’s General Fund would have received about $819 million of General Fund property tax had revenue kept up with inflation and population growth since 2001. Actual revenue was about $419 million, a $400 million difference.”

Next year in what’s widely expected to be the capstone of a four-term run as county executive before passing the baton, Constantine may chart a plan to mitigate Metro’s fiscal cliff at the same time as he faces these other challenges in his 2026-2027 budget. But with limited options to raise revenue or control costs available to the County, the storm clouds ahead look fairly ominous.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.