Despite the major budget shortfalls the County is facing — particularly when it comes to Metro’s massive deficit — Peter Kwon isn’t a fan of proposing any new taxes under almost any circumstance, and certainly not until he can take a good look at the County’s budget.

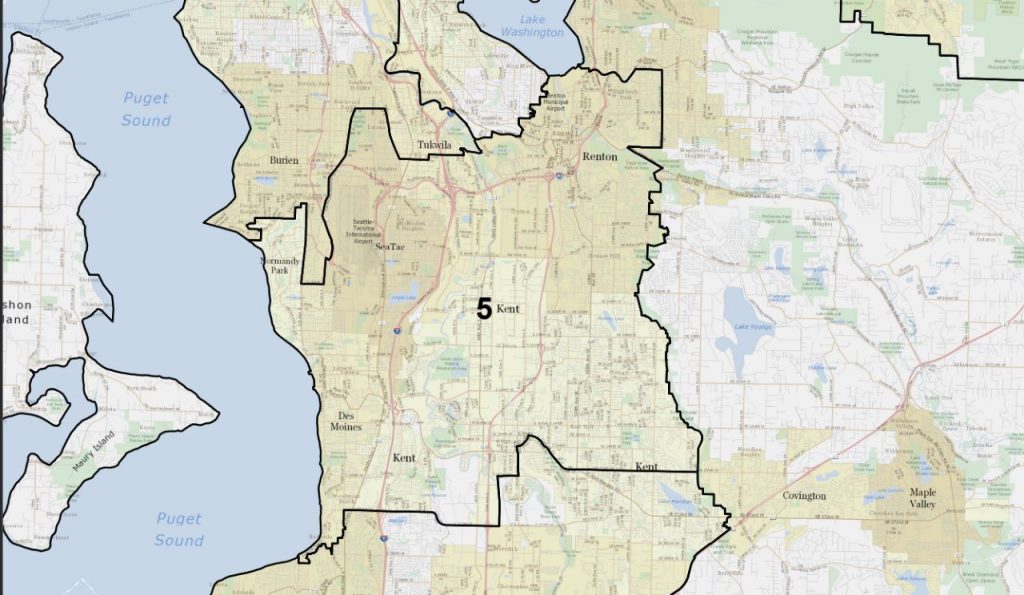

While Kwon came in first in the August primary with nearly 28% of the vote in a six-way race, his campaign’s message had been high-level and light on specifics. District 5 voters may not have a very firm idea of what Kwon hopes to accomplish at the County Council — at least beyond avoiding new taxes. (Kwon declined to return a questionnaire to participate in The Urbanist’s endorsement process.)

Kwon is facing off against Steffanie Fain in November’s general election for King County Council’s District 5 seat. Earlier this week, The Urbanist published our interview with Fain.

A current SeaTac city councilmember, Kwon spoke with The Urbanist in August about his stances on a number of issues, including Metro’s looming budget shortfall and affordable housing.

Kwon questioned how King County could come up so short in revenue. Last year, he said, the County collected more than $10 billion in revenue, a record-setting collection number — “and this year, they came up $125 million short.”

“And so this year, they had to implement an additional sales tax in the name of public safety, the public safety sales tax,” Kwon said. “How can they be collecting the most amount of revenue, historical numbers, and yet still come up short? We need to do more of a deep dive into the finances and make sure that the budget is being balanced correctly and spent wisely, because at the end of the day, you can’t do anything else if you don’t have enough money to pay for it.”

Kwon contrasted the County’s decision to implement a new sales tax to support public safety funding with his own work on SeaTac’s council. When he was first elected 10 years ago, Kwon walked into a city with a shortfall of between $1.3 and $2.5 million — hardly the same level King County is facing, but, he said, “the city of SeaTac only has a population of 30,000, and so it was a lot.”

Kwon attributes his and his colleagues’ deep-dive into the City’s budget to create a managed reduction program that brought the City up to a $2.5 million surplus within six months. As a result, for the last 10 years, Kwon said, the City has not had to raise taxes or implement new ones. He said that it has had increasing surplus revenues since then, and has been able to pursue “major capital improvement projects,” such as expanding park space, hiring more staff, and providing more funding for human and social services. He said they are also discussing a new civic center.

The data Kwon sent doesn’t reflect increasing surplus revenues, but it does show that the city has not fallen into another deficit and that revenues have, to some degree every year, outpaced expenditures since 2016.

Kwon said that in his own experience, it pays to go through budgets line by line. For instance, he said, one of the things he discovered, after being elected, was that different departments all used different printing companies, rather than one printing company. These companies, he said, all charged different prices, and he found that there was no uniformity to the prices in a way that allowed for proper budgeting. He proposed that the city go with one locally owned, family-run company to meet its printing needs, rather than a different one for every department.

“As a result, the city was able to save somewhere around, maybe, 30% or more just on printing costs alone,” Kwon said. “And that was a lot, because it’s not a one-time saving, this was an ongoing saving year after year.”

Metro Transit

Kwon said that he thinks Metro’s biggest budget shortfall lies with fare enforcement, which had already showed signs of slowing before the Covid-19 pandemic, and fell off a proverbial cliff starting in 2020.

The Metro Bus Farebox Recovery data from the County’s most recent Metro performance report shows that Metro’s fare collection has not bounced back to pre-pandemic levels, and has stayed nearly stagnant for the last three years.

Kwon said that he supports elders and students not having to pay full fares, but that “able-bodied adults should be paying what the fare is.”

Metro has dipped into reserves to make up for declining revenue and rising operating costs, but that approach will soon become untenable. Even an optimistic scenario for increasing fare revenue isn’t likely to cover the gap on its own. Metro projects to have an estimated $500 million shortfall by the 2028-2029 biennium, fully exhausting reserves by the following biennium. Sales tax revenue is Metro’s largest source for its billion-dollar transit operating budget, while fare revenue is projected to bring in $100 million in 2025.

When asked whether he would support additional revenue for Metro, Kwon said that he might, but only after getting more information. As far as potential sources of revenue, he said, “there are federal transportation grants that are always available. There are also state grants that are always available.”

“There are also things like the lodging tax that could potentially be used for public transportation because it does support and promote tourism as well,” he said. “There are existing revenue sources that could be pursued that might be available. … It’s not something that I would be able to pinpoint right now and say, okay, this is the new revenue source.”

Kwon stopped short at increasing taxes, specifically because “the cost of living is just increasing. And that’s one of the challenges that I’m hearing from a lot of residents, especially in South King County, is that they’re getting priced out of the area.”

Affordable housing

Affordability is an ongoing issue in the Seattle area — and, increasingly, into South King County. A dearth of affordable housing options means that many King County residents are increasingly cost-burdened, as cost of living outpaces wages, and they are forced to pay more every year relative to what they earn to stay housed.

Earlier this year, InvestigateWest found that, across the state, landlords who operate affordable housing units have started serving eviction notices at historic levels, as pandemic protections expire. In King County alone, eviction filings in January 2025 were 66% higher than they were prior to the onset of the pandemic. This year’s state eviction rates are on track to outpace even last year’s, which was 53% higher than in 2019.

Kwon doesn’t support a county-wide measure to fund affordable housing that involves any new taxes. He said instead that he supports private-public partnerships, like the one SeaTac recently entered into at Angle Lake that serves those at 50% and 60% area median income. The building’s developer, Mercy Housing, funded the development through a mix of private and public sources, including Amazon, King County, and the Washington State Housing Finance Commission.

He said he also supports more private development of affordable housing, and pointed to Polaris at SeaTac and Adara, a mixed-use residential housing project, as an example.

Asked what kind of housing he would like to see built, Kwon said he would like to see “a lot more focus on redevelopment or new development of vacant, underutilized properties along light rail stations, along major transit routes, transit hubs, areas like that.”

“That’s what I would like to see more of,” he said. “I would also like to see more public-private partnerships so that everyone is working together to achieve a common goal. And at the same time, I would like to see more ground floor commercial space included in these new multifamily residential developments.”

Kwon said that if the County wants to solve its affordable housing crisis, it needs to focus on creating affordable housing in areas where there is also easy access to transit.

“And that would solve two problems: Number one, it would solve the lack of affordable housing,” Kwon said. “But number two, it would also solve the accessibility issue of folks who would like easier access to public transportation.”

With few exceptions, transit-rich areas are already where builders focus their affordable housing projects.

“Entire bus stops… are shut down [in Kent],” Kwon said, pointing to cancelled bus routes. He said he did not know why this was an issue, but assumed that part of it may be due to low ridership, low funding, and shortage of workforce.

“It could be a combination of all of those, right?” he said. “But at the end of the day, things like that are a disservice to the community, because when you see a public service or a public amenity that has been available, and then all of a sudden it’s taken away, that really, that really upsets a lot of people.”

At its Sept. 5 meeting, the Kent City Council took issue with King County’s proposal to cut Route 162, as part of its South Link Connections bus restructure ahead of the Federal Way Link light rail opening, as well as its assumption that elders and immigrants would know how to use the MetroFlex app, the Kent Reporter reported. Councilmembers said that the County is once again opting to try to cut a Kent bus route without addressing what one councilmember called “a transportation desert north of SE 240th and the overall transportation inequity in SE King County.”

Regressive taxes, vulnerable communities

Washington state ranks as the second-worst state in the country when it comes to regressive taxes, falling behind only Florida.

Kwon said that he will do everything he can to ensure that local taxes are not regressive, and that the cost of living is as low as possible for people, particularly those who are at highest risk of displacement. He said that this is an issue particularly near and dear to his heart, because SeaTac has “among the highest poverty rates out of any city in the entire county.”

And, of course, this does not mean increasing taxes.

“If you’re increasing taxes on the residents, that really doesn’t help everybody,” Kwon said. “In fact, it generally ends up harming the people who can least afford to pay. On the flip side, we need to make sure that we are providing the services that are available for the lowest income bracket.”

He would like to implement programs in King County similar to those in SeaTac. For instance, Kwon said, the city puts 1.5% of its general fund towards human service agencies that provide services and programs to the public, free emergency assistance like mobile home roof repair, and free public entertainment.

Kwon also said that he supports restoring and expanding a number of programs that President Donald Trump’s actions have severely hobbled, such as health care, food assistance, and housing, and those that Trump’s actions have put in jeopardy, such as access to family planning providers.

Before committing to any way to fund such programs — new or restored and expanded — Kwon said he would have to dig into the budget, first, and that he would consider private-public partnerships over tax increases.

Organizational restructuring

The King County Regional Homelessness Authority (KCRHA) has come under fire recently for a suite of issues, including, recently, its director coming under investigation for alleged racial bias and creating a “toxic work environment.”

When asked for his thoughts on the agency, and what he would propose to do with it, if elected, Kwon said that he thinks there may be merit in combining KCRHA with organizations like South King Housing & Homelessness Partners (SKHHP) that appear to have “overlapping, perhaps even identical goals.” Since SKHHP is a partnership of South King cities rather than a countywide entity, such a merger clearly faces logistical barriers.

Kwon argued merging agencies or programs could be a solution for other organizations.

“How many other multiple organizations are there that are trying to do the exact same thing that are basically each independently being funded?” Kwon asked. “Can’t we combine all of this into one effort and achieve a better outcome, or a more immediate outcome, or make a bigger impact at the end of the day?”

It’s a similar refrain that policymakers have long made and that inspired the launch of the KCRHA in the first place. And yet, five years into the homelessness authority’s existence, synergies have been limited and many problems stubbornly persist.