Seattle’s update to the Multifamily Tax Exemption would increase the program’s inclusivity and expand access to a wider pool of renters.

In Seattle, most strongly agree that our ongoing housing crisis is an ‘all hands on deck’ scenario that means embracing a wide range of creative tools to help us build more housing at all income levels.

This line of thinking is the cornerstone of Ezra Klein’s Abundance philosophy. It’s consistent with the support voters overwhelmingly gave to creating a new Social Housing Public Development Authority earlier this year.

It’s also why voters have said yes to taxing themselves more than $1.6 billion over the course of six housing levies that have created 11,000 housing units over a 39-year period. It’s the thinking behind the City’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA program), which has built more than 4,700 low-income units and raised $300 million for new low-income housing.

But here’s the head-scratcher: There’s only one Seattle program that middle-income renters have traditionally benefited from — the Multifamily Tax Exemption Program (MFTE).

And yet some are advocating that this should become another lower-income tool, leaving middle-income renters with no options for finding below-market housing.

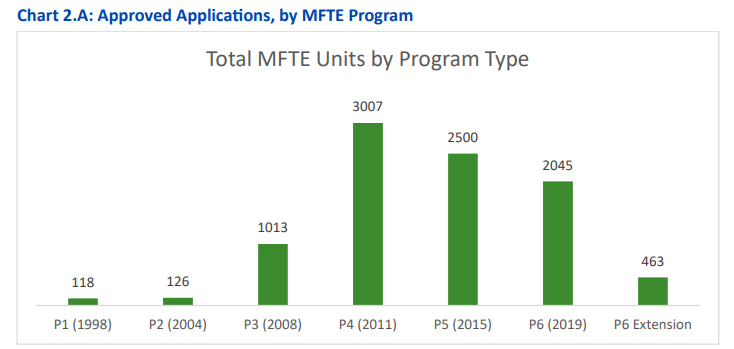

Originating in 1998, Seattle’s Multifamily Tax Exemption Program (MFTE) is a voluntary incentive program that developers can opt-into and has created more than 8,000 below-market units – nearly as many as the Seattle Housing Levy. The program has been a valuable tool in Seattle’s housing toolkit. To qualify for participation in Seattle’s 12-year MFTE program, buildings set aside at least 20% of the apartments for workforce housing. In exchange for this discount, the building receives property tax exemption for the year it participates.

The property tax exemption was not meant to be a 1:1 financial tradeoff in exchange for the workforce housing. Rather, it’s designed to be an incentive for the developer to build the whole project, with the goal of also building the workforce units, aiding in the feasibility for housing production as a whole. Because, as the theory of Abundance goes, and as Seattle’s own local experts have researched, one critical component to truly solving the housing crisis is to build more housing at all income levels.

MFTE’s Program 6, which spans 2018 to now, lowered rent limits (set as a percentage of area median income or AMI) to low-income levels and voluntary program participation by developers dropped by 50%.

This is why Program 7, which is currently before the City Council, aims to right-size this issue, bringing AMI rent limits back to middle-income housing levels, which is what the program was intended to create.

Some argue that increasing these AMIs equate to raising rent for new MFTE renters. I suppose that’s one way to look at it – but in reality, raising AMIs back to middle-income AMI levels means increasing program inclusiveness.

That’s the ah-ha moment.

Increased AMIs in the MFTE program translated to equitable access. It’s returning the opportunity for renters who earn between 65-90% AMI their one tool they had access to for a rent discount.

This is what the voluntary program was always meant to do. It was not meant to replicate subsidized housing, which the Housing Levy, MHA and nonprofit builders create, it was meant to complement it. In fact, our company has a building with both City-funded affordable units, and MFTE designated units at higher AMI’s, allowing the property to house a wider range of our renters at below-market rents.

For example, if an affordable unit is set at 60% AMI or below, that means that renter cannot make more than $66,000 annually.

What if you earn $70,000 annually? Instead of a discounted rent unit targeted at your middle-income bracket, you need to try and afford market-rate rent?

That’s a head-scratcher.

Middle-income renters are also extremely cost burdened and should not be left behind.

Perhaps most importantly, if P7 doesn’t work well, then the property owners who have 8,000 units in the program now won’t elect to renew at the end of the 12-year time horizon. That means an immediate rent increase for thousands of renters and a massive loss of middle-income housing for our city.

Keeping this safe harbor for renters should be a top priority for all of us on the frontlines battling for more affordability. Not voting to adopt P7 now, after almost a year of work has gone into this moment, in favor of yet more discussion, is putting process over progress.

Seattle is proudly one of the most progressive and inclusive cities in the nation and it’s why those of us who live here love to call it home.

We owe it to middle-income renters to fix MFTE. Let’s continue to focus on the big picture – we need housing at all income levels for our city – and our renters – to win. That’s the abundance we all should look forward to celebrating.

Emily Thompson

Emily Thompson is a partner with GMD Development, a local mission-driven development company dedicated to developing affordable and workforce housing in Seattle and the greater Pacific Northwest. She is active in discussions around funding and policy to make housing solutions in our region more plentiful, equitable, and affordable.