Earlier this month, the King County Department of Public Defense (DPD) released a report showing that the City of Seattle has fallen short on offering diversion and treatment to people criminalized by its new 2023 drug ordinance.

The DPD report used almost two years of publicly available data to analyze the impacts of this new law, and what they found validated criticism of the ordinance when it was being passed. During the reviewed period, only six prosecutions out of 215, or 2.79%, resulted in someone either completing treatment or receiving a court order directing them to seek treatment.

Simple drug possession or public use was the only offense in 76% of the cases found, but 42% of the people charged solely with one of these offenses were still booked into jail. 71% of the cases involved a very small amount of drugs (a gram or less).

The report revealed that the new ordinance is disproportionately criminalizing and harming Black people. 25% of the people charged with public drug use or misdemeanor drug possession have been Black, meaning a Black person is 4.1 times more likely to be charged with the new drug ordinance than a White person.

“The harmful impact is mirroring what we used to see in terms of the disproportionate impact on communities of color, particularly Black men,” said Matt Sanders, the Director of DPD. “It is very concerning for us because it’s starting to look more like a return to the war on drugs, something that we’ve moved away from.”

Promise to prioritize diversion

Seattle’s 2023 drug ordinance created new gross misdemeanors for public drug use and simple drug possession in the wake of the state Supreme Court’s Blake decision in 2021. The law reflected the actions of the state legislature earlier in the year, who adopted the same drug laws. The state went that route in spite of its own Substance Use Recovery Services Advisory Committee (SURSAC) voting to recommend the decriminalization of simple drug possession in Washington State.

The state ordinance identified pre-filing or pre-trial diversion as a preferred strategy, and Seattle’s ordinance followed suit, stating both an encouragement of and preference for law enforcement assisted diversion programs, specifically naming the Let Everyone Advance with Dignity (LEAD) program.

Seattle’s ordinance was strongly backed by Seattle City Attorney Ann Davison and Mayor Bruce Harrell.

“Our ordinance will talk about how we deal, what we’re required to do for that person who just needs help,” Harrell said at the time. “It’s not a war on drugs. It’s a war on health. We want everyone to be healthy.”

The city council voted narrowly (4-5) against the first version of the ordinance in June 2023, with then-Councilmember Andrew Lewis seeming to change his mind about his vote on the dais.

“I came out here on the dais today fully prepared to vote for this measure… but this discussion deserves more than this,” Lewis said right before the vote.

However, Lewis brought a new–and largely similar–version of the ordinance before the council in September 2023, which passed by a 6-3 vote. Lewis said at the time that the new ordinance emphasized services and diversion.

The City didn’t increase its investments in treatment and diversion at the time of the ordinance’s passage.

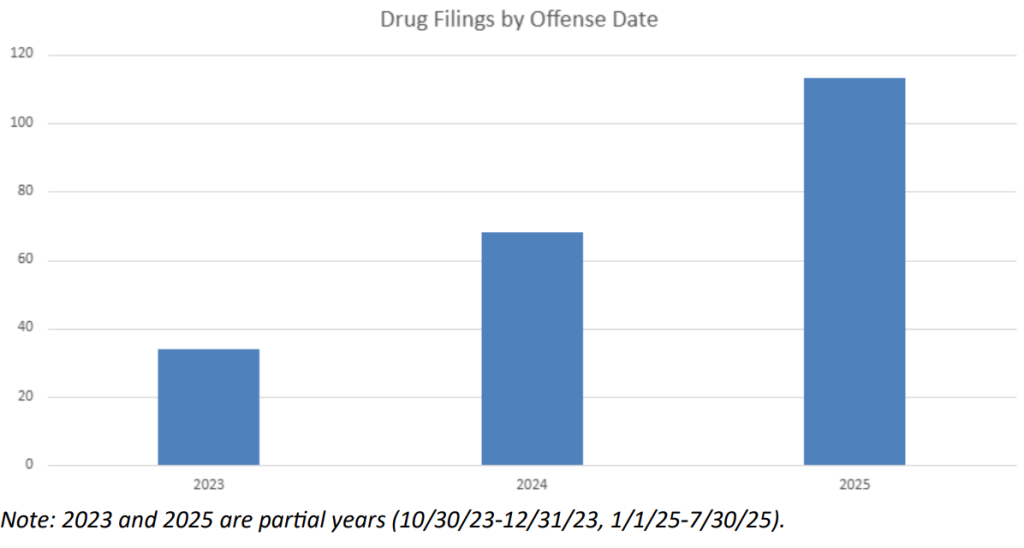

Prosecutions increasing this year

The DPD analysis of the drug ordinance found that related prosecutions have increased in 2025. This year through the end of July 2025, the Seattle City Attorney’s Office (CAO) filed nearly double the number of cases related to violations of the drug ordinance compared to the entire previous year. In 2025 the office also increased the pace on prosecuting older cases from 2024.

The report states that these new trends mark “a clear shift in enforcement strategy from SPD and CAO that contradicts the ordinance’s stated preference to avoid criminal legal system involvement and incarceration for people struggling with substance use in public.”

CAO has also ramped up the use of Stay Out of Drug Areas (SODA) orders. According to data from the Seattle Municipal Court, only one SODA order was issued in 2024. As of October 16, 60 SODA orders have been issued thus far in 2025.

Part of the increase in SODA orders may be caused by the CAO’s recent Drug Prosecution Alternative program, announced in May and launched in August. The program offers defendants charged with drug use or possession the chance to have their drug charge dismissed if they engage in evaluation for treatment.

Seattle CAO spokesperson Tim Robinson, told The Urbanist most people said they would take the deal if offered. “In the past six weeks, that offer has been extended 25 times and 17 have opted in. Only one person has rejected that offer so far,” Robinson said.

Unlike with diversion, the required evaluation for this program can sometimes take place months after the original incident resulting in the charge took place.

“With someone in crisis or someone with addiction, months can be the difference of someone you know overdosing or life or death,” Erika Evans, the current frontrunning candidate in the City Attorney race, told The Urbanist. “It’s unacceptable. It’s a continued pattern and practice of [Davison’s] leadership of delays, delays, delays, and not actually having any evidence-based approaches to what the office is doing, especially on the criminal side.”

If the incident occurred in one of Seattle’s many SODA zones, the Drug Prosecution Alternative agreement also requires defendants to join the CAO’s request for entry of a pre-trial SODA order. This new requirement is likely to increase the total number of SODA orders issued.

“Courts are very reluctant to impose these SODAs for a number of reasons,” said Sanders. “And so if you’re trying to show that these sort of orders are being issued, one of the ways you can try to do that is to coerce a person into agreeing to one in order to get their case dismissed.”

Other criticisms

Evans was strong in her condemnation of the CAO’s new approach to the drug ordinance, citing the ordinance’s original intention to prioritize diversion and services.

“These are the 215 cases that the City Attorney has made basically a war on drugs,” Evans said. “When 215 folks that are under her discretion, 97% of them are not getting treatment, that is a failure, and seeing that Black people are represented 4.1 times more than White people in this group, that is very frustrating and disappointing to see.”

Evans criticized Davison’s Drug Prosecution Program, saying it’s a method for getting rid of cases instead of helping people get connected to services and treatment. Evans would prefer to see cases similar to these 215 referred to LEAD. Evans suggested, and Lisa Daugaard, the co-executive director of Purpose Dignity Action (PDA), confirmed that LEAD is willing and able to take cases like these.

Studies show that the risk of an overdose greatly increases after someone is released from jail, calling into the question the increasing jail time associated with simple drug charges.

Meanwhile, more than half of the 215 cases in the DPD report stalled out after a bench warrant was issued, meaning that the person didn’t appear in court at the specified time an their whereabouts are now unknown. These people don’t receive any services or addiction treatment, while their lives might become further destabilized by having a pending criminal charge.

The CAO’s new direction of increased filing and jail time also carries a hefty price tag. The City of Seattle entered into a new interlocal agreement with King County to use the King County Jail, with the negotiated price to house someone in the jail in 2025 being $386.36 per day. The City also pays a booking fee of $296.46 every time a person is booked. Therefore, the minimum amount the City pays every time someone is put into the jail is $682.82, an amount that can quickly balloon for longer stays.

Using the Drug Prosecution Program instead of pre-filing diversion entails additional prosecuting and public defense attorney costs as well as court costs, all of which are paid for by taxpayers.

“It has cost cascading effects because it hurts the individual who is now being criminally prosecuted, is not getting any services, and is subjected to potential jail time, and costly to the taxpayers who now have to pay for the infrastructure to support this machine with lawyers and judges and court time,” Sanders said. “And there isn’t any corresponding benefit to the public or public safety.”

“To be making us pay for something that is clearly ineffective, clearly a failure, clearly racially disproportionate […] of who it’s applying to, and it’s not solving what we’re seeing on our streets, what’s happening is bad stewardship of public dollars and of public safety,” Evans added.

Harrell and Davison double down

Both the Mayor’s Office and the CAO contend that the DPD’s report is misleading, with Robinson saying the report presents incomplete data. Unfortunately, some relevant data, particularly that related to Seattle’s diversion efforts, is not easily available to the public.

Both the Mayor’s Office and the CAO also said that the report ignores the diversion to LEAD that has been happening. Callie Craighead, a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office, provided a joint statement with LEAD arguing for the program’s success.

“During that time frame, while 215 individuals’ cases were referred for prosecution, SPD referred three times as many people directly to recovery services and case management through the LEAD (Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion) framework,” the Mayor’s Office and LEAD said. “75% of those encountered by SPD were diverted prior to jail booking or prosecution. The City has kept its promise.”

The joint statement emphasized that the ordinance doesn’t legislate in the area of prosecution, seemingly passing the buck onto the CAO: “The aspects of implementation of the possession/public use ordinance that are under the Mayor’s control (police implementation and LEAD funding) have played out exactly as promised.”

LEAD’s 2025 Quarter 2 report tells a different story, saying, “Seattle LEAD has faced significant budget reductions in 2025. In Q2, Seattle LEAD downsized its workforce, which puts all of the above projects at serious risk of failure.”

Harrell has proposed a $5 million investment in LEAD in the 2026 budget, to be funded by the new 0.1% public safety sales tax that the city council just passed. Much of this investment is replacing the funding LEAD has lost over the last two years.

Robinson shared different diversion numbers, covering the timeframe from October 2023 to the present. He said 222 people had completed a LEAD intake, which means they weren’t booked into jail or charged, while 236 people were charged with a crime. These numbers show a diversion rate of 48%.

“Without a law to make drug use or possession unlawful, officers could not make arrest-referrals to LEAD or the City Attorney’s Office,” Robinson said.

Sanders is not convinced by these arguments, saying the ordinance isn’t necessary for the police to make referrals to LEAD.

“Why are all these people, hundreds of people over the last two years, still getting prosecuted for just drug possession?” Sanders said. “Why are you four times more likely to get a drug prosecution charge if you’re a person of color?”

“There’s nothing in the legislation for the intent of the bill to say only three quarters of people should benefit from treatment programs, pre-diversion,” Sanders continued. “It seems like an arbitrary line to measure success. The goal is to divert as many possible cases, and the goal is also not to have a disproportionately harmful impact on communities of color.”

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.