By 2040 the Puget Sound region is expected to have a population of 5 million, up from 3.9 million today. Seattle expects to be at the center of this growth and is planning for 120,000 new residents in 70,000 housing units, along with and 115,000 new jobs, over the next two decades. The latest iteration of the Seattle’s comprehensive plan, known as Seattle 2035, is taking public comment through Friday and is due to be adopted next year. An open house with City staff in West Seattle last week provided a glimpse into how this guiding document will shape future policies.

The Northwest Urbanist been following Seattle 2035 since the kickoff event nearly two years ago. In that time the City has been actively updating and refining the plan’s many goals and policies to reflect current public opinion and best practices.

The plan is due to be adopted sometime in 2016 even though state law required the plan be wrapped up earlier this year (as it also did for all King, Pierce, and Snohomish County jurisdictions). But the City did fulfill its legal obligations under the Growth Management Act by adopting a number of technical updates for the 2015 amendment cycle. The amendments included updates to demographic data, inventories, analyses and forecasts of growth in development and employment, environmental policies, and changes to textual references and maps.

The planning process continuing into 2016 is therefore voluntary. Creating a wholesome plan is a good sign of the City’s intentions to hear from a wide swath of the community and develop a useful document.

In a separate but parallel process the Department of Planning and Development (DPD) has created a draft environmental impact statement that presents four alternative land use scenarios. According a staff member at the open house, public feedback and DPD is leaning towards Alternative 4. The Urbanist described it as envisioning “…growth for urban villages near frequent transit, which includes both high quality bus and rail service — not just light rail. More urban villages would be slated for increased growth capacity than conceived by Alternative 3, including expanded urban villages in Ballard, Crown Hill, Fremont, and Alaska Junction.”

The draft Growth Strategy chapter, an element of the plan not required by state law, reflects this approach. Seattle’s urban villages are where the majority of growth has already occurred over the past 25 years, and that’s no accident. Most urban villages are essentially islands of multi-family and commercial zoning amid seas of single-family homes. To achieve the designation, the villages must also have “frequent” transit service to multiple destinations, which is typically defined as at least every 15 minutes during most of the day.

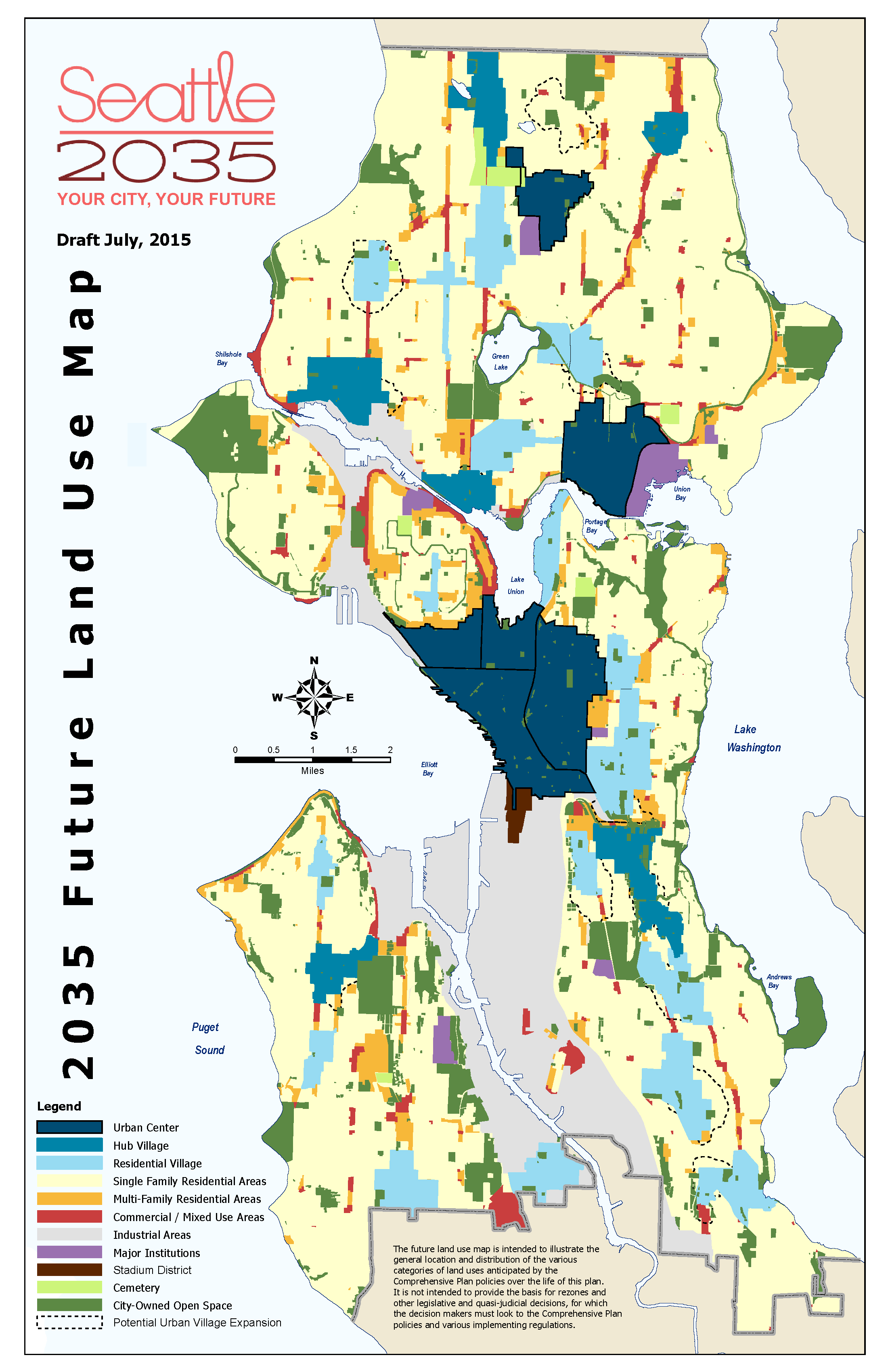

The updated future land use map proposes expanding 12 village boundaries to include areas within a 10-minute walk of frequent transit stops. Six of the expansions are directly related to light rail stations while three in West Seattle and Ballard seem to be related to RapidRide bus service. And, significantly, an entirely new urban village is proposed around a future light rail stop at NE 130th Street. These changes will be most obvious in the form of upzoning low-density areas to better utilize infrastructure investments.

However, a balance must be struck between growth and displacement. It is an irony of city planning that the same high-frequency public transit and walkable shopping districts that perhaps most benefit low-income residents are also more likely to force them out of their homes as land values increase and redevelopment occurs. Therefore, in areas with a high risk of involuntary displacement (illustrated in the map below), DPD may slowly phase in upzones rather than implementing sweeping changes. This is especially relevant for the low-income residents and small businesses in southeast Seattle. It would also provide more leverage for the City to mandate affordable units and generate housing funding by allowing new affordable housing programs to kick in before redevelopment occurs.

In addition to the Growth Strategy chapter, three other elements in the plan are not required under state law: Arts and Culture, Community Well Being, and Neighborhood Planning. They are each relatively short, but simply expanding these topics into standalone chapters makes them more relevant and visible to policymakers while reaffirming the City’s ability to work on a variety of issues simultaneously. The Arts chapter alone refers to social equity, declaring, “Making arts and culture accessible to all requires that the City take extra effort to promote inclusion…”, while also presenting economic issues: “[Historic] preservation is integral to our economic development planning, and it enhances our city’s attraction as a center for tourism, an important source of local jobs.”

The Community Well Being chapter (renamed from Human Development in the current plan) is particularly unique and presents policies on public health, safety, education, and social connections. One goal is: “Make Seattle a place where everyone feels they can be active in family, community, and neighborhood life; where they help each other, contribute to the vitality of the city, and create a sense of belonging among all Seattleites.”

The other chapters are standard across most Washington State jurisdictions: Land Use, Housing, Transportation, Economic Development, Parks and Open Space, Capital Facilities, Utilities, and Environment. DPD has prepared ten broad proposals that encompass parts of all of the plan’s chapters:

- Guide growth to areas within a 10-minute walk of frequent transit.

- Continue to monitor changes citywide and in urban villages.

- Create a future land use map that provides more flexibility in changing between commercial, mixed-use, and residential development in urban villages.

- Increase the diversity of housing types in lower density residential zones.

- Designate a Stadium District where housing and hotels would be permitted while protecting freight mobility.

- Minimize displacement of marginalized populations as Seattle grows.

- Accommodate six key functions in the public right-of-way: mobility, access for people, access for commerce, activation, greening, and parking.

- Set goals for parks and open space that focus less on quantity and more on quality, equity, and proximity to jobs and residences.

- Update neighborhood planning policies to reflect current practices.

- Locate schools to better service Seattle’s growing population.

There are many examples of more nuanced goals and policies in the plan that support these proposals. And much of the plan’s language has an emphasis on social and racial equity, a result of an initiative to be more inclusive in policy development and project planning. The City’s ongoing Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda, with ambitious goals for providing housing to low-income residents, also heavily factors into the plan. This is borne out in specific policies, like H3.2 from the Housing chapter: “Explore ways to align development and design standards with strategies for extremely low‐, very low‐, and low‐income housing, in order to encourage housing production and preservation in urban centers and urban villages in order to increase attractive and affordable housing options for households of varied sizes, types, and income levels, including families with children and mixed generation households.”

In the realm of transportation the plan doesn’t tiptoe around the fact that the City discourages solo car travel. LU6.4 suggests: “Consider setting parking maximums in urban centers, urban villages and other areas served by high‐capacity transit in recognition of the increased pedestrian, bicycle and transit accessibility already provided or planned for in these areas.” Policy T3.10 from the Transportation chapter itself states: “Prioritize bicycle and pedestrian investments on the basis of increasing use, safety, connectivity, equity, health, livability, and opportunities to leverage funding.” However the Transportation chapter doesn’t include much discussion on emerging services like car share and bike share, which may dramatically reshape how people move around the city 20 years from now.

Seattle also recognizes the need to transition away from level of service (LOS) as a transportation planning metric. LOS represents the delay to drivers caused by traffic congestion. Most cities mandate a certain LOS standard (measured from A to F), but the result is things like excessively wide streets, dedicated turn lanes, and wide curb radii which dissaude people from traveling in anything but a car and further aggravating traffic issues. In urbanized centers like Seattle, LOS makes little sense because streets physically cannot be expanded to the meet the standards, but Washington State mandates that the City include it in the comprehensive plan anyway.

Seattle recognizes this discrepancy and says it is “…considering alternative methods of level of service standards that consider all travel modes, which is consistent with the multi‐county planning policies in Vision 2040 and with other City policy objectives.” California is the first state to ditch LOS as a planning consideration and now examines projects based on the impacts to vehicle miles traveled, a more relevant metric.

There’s much more to the plan than what is covered here, but broadly it appears to be a successful culmination of best practices in city planning and a reflection of recent changes in housing prices and transportation modes across the city. The draft plan is officially taking public comments through tomorrow, November 20th. Visit the Seattle 2035 website to learn more about the plan and submit your thoughts on any of its goals, policies, and vision.

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.