Scientists tells us that global temperatures are likely to rise somewhere between 2.7°F to 8.6°F by the end of the century. It’s a bit of a spread to be sure, but the increase in global temperatures will be not equal. As a recent report suggests, temperatures in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia could top 140°F by 2100. That coastal city on the Persian Gulf already experiences normal temperature maxims at around 104°F, which can feel a lot more like 140°F with moderate-to-high humidity. For the average person though, it doesn’t take too much heat and humidity to threaten heat exhaustion or even death. Temperatures above 95°F, in combination with humidity, are generally considered a key threshold.

Dhahran isn’t an isolated instance of how global climate change can have far reaching effects. It can manifest itself in many other ways that seem less obvious. Some of those include change in vegetation, annual precipitation rates, and local and regional cyclical weather patterns. At the far reaches of the globe, the melting of icecaps is aggressively accelerating. Yet since polar regions are sparsely populated, the major impacts resulting from that go largely unobserved by most of civilization.

Locking In Climate Change

Debate has varied widely on the exact causes and even the existence of global climate change. But those who acknowledge it fall largely into two camps: those who lay blame on anthropogenic causes (human actions) and natural cyclical changes. But regardless of what people actually think, the data strongly suggests that major climatic shifts are already locked in. And if further action isn’t taken to curb greenhouse gas emissions, additional temperature rises could be locked in leading to even greater global devastation.

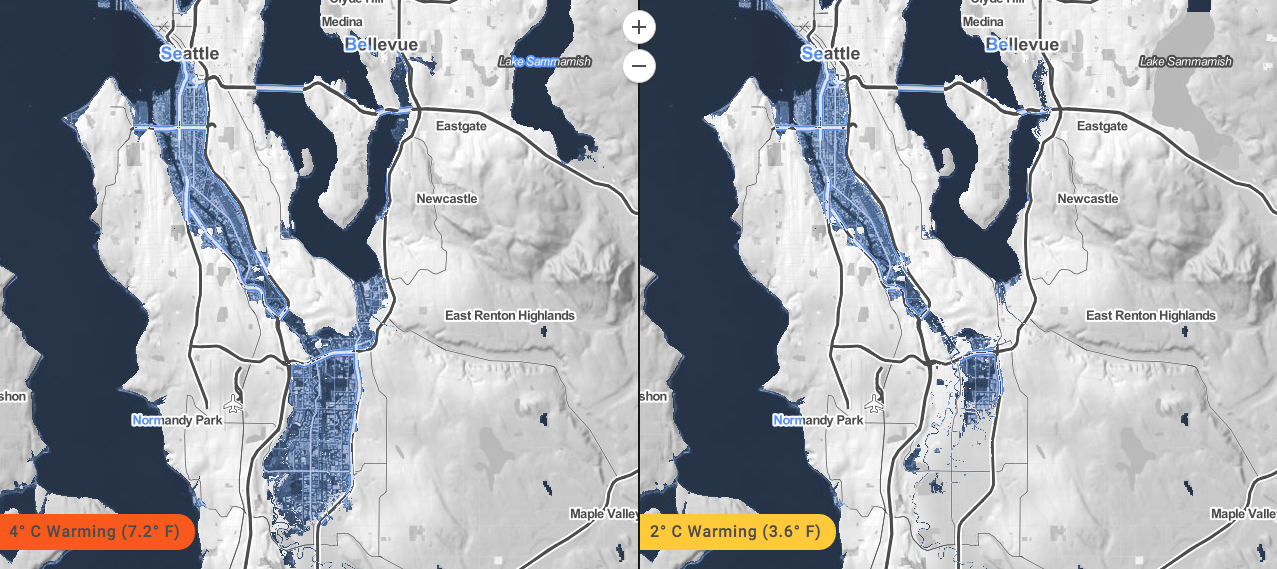

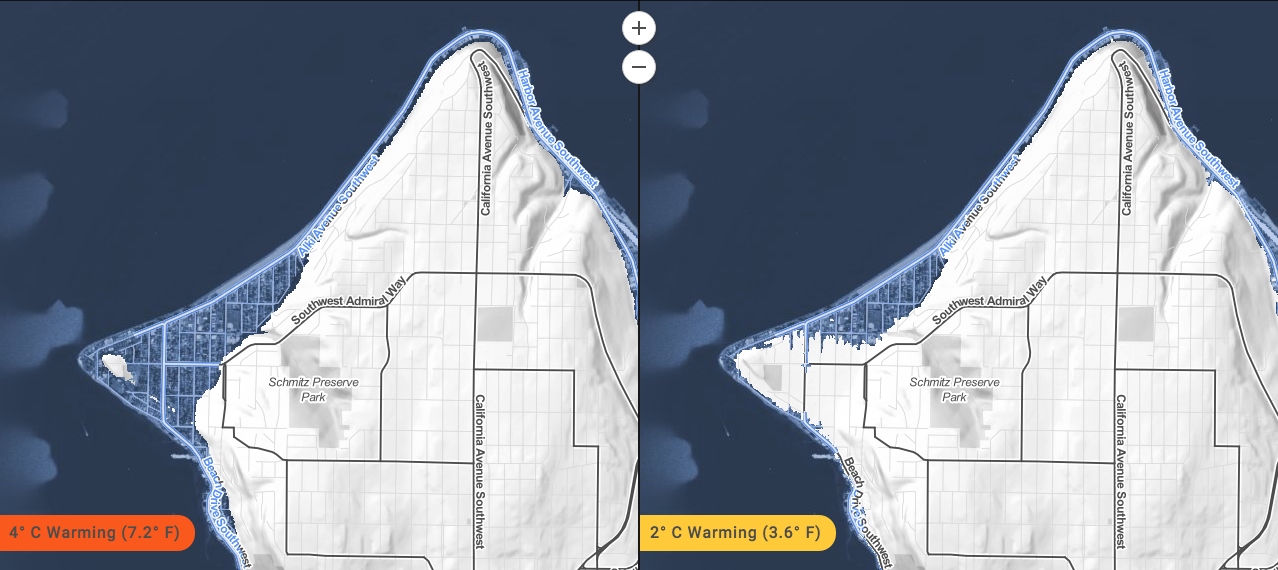

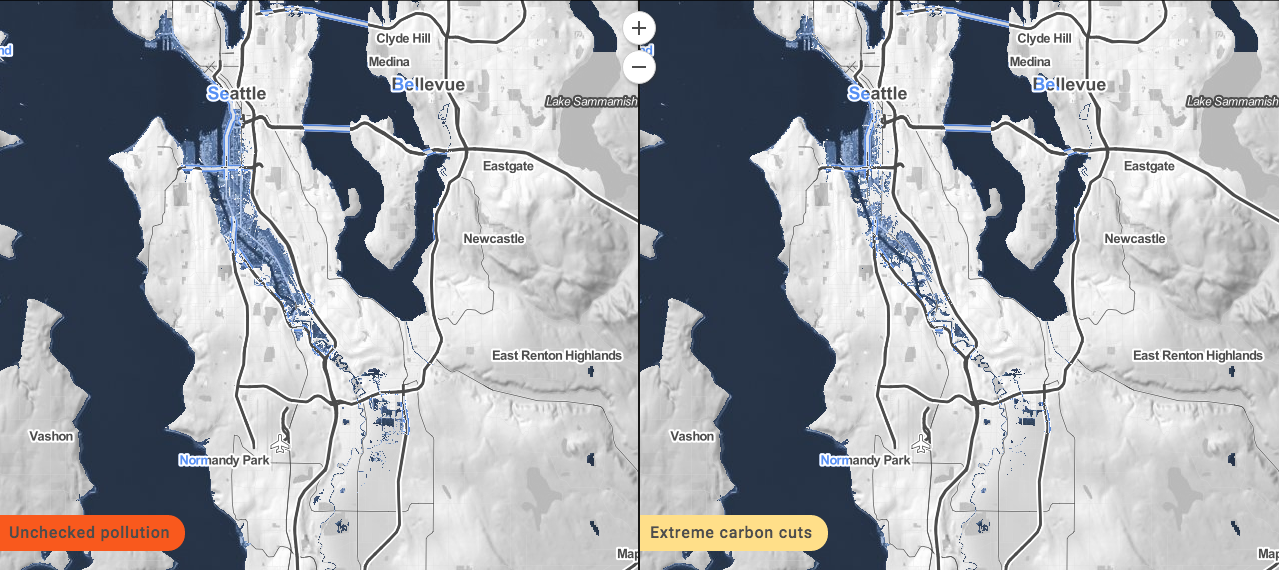

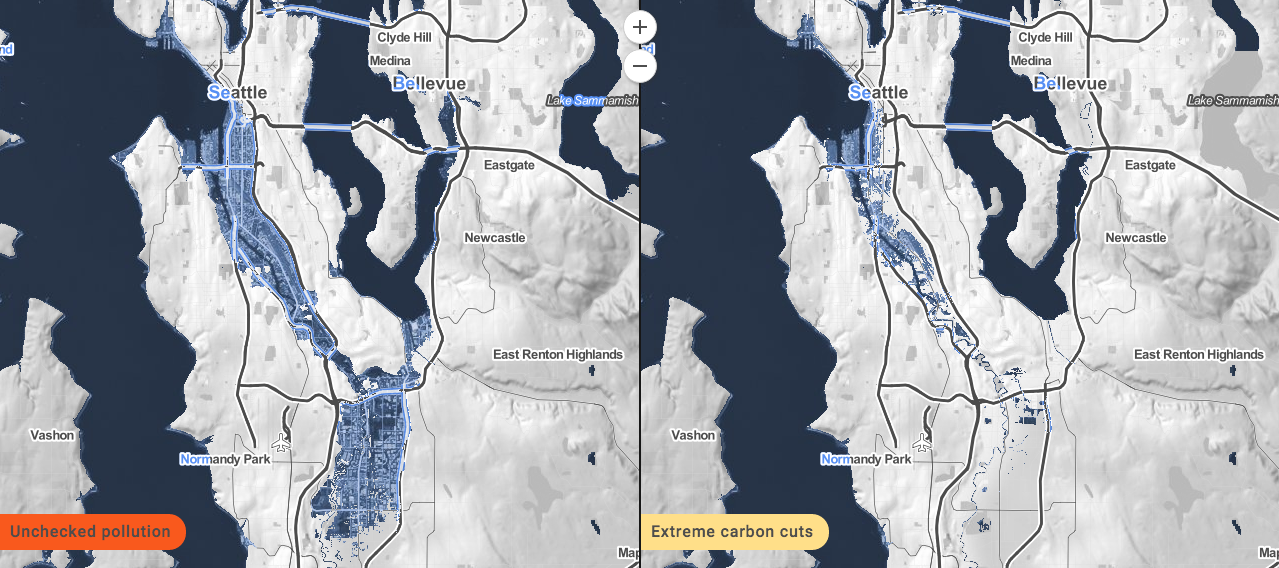

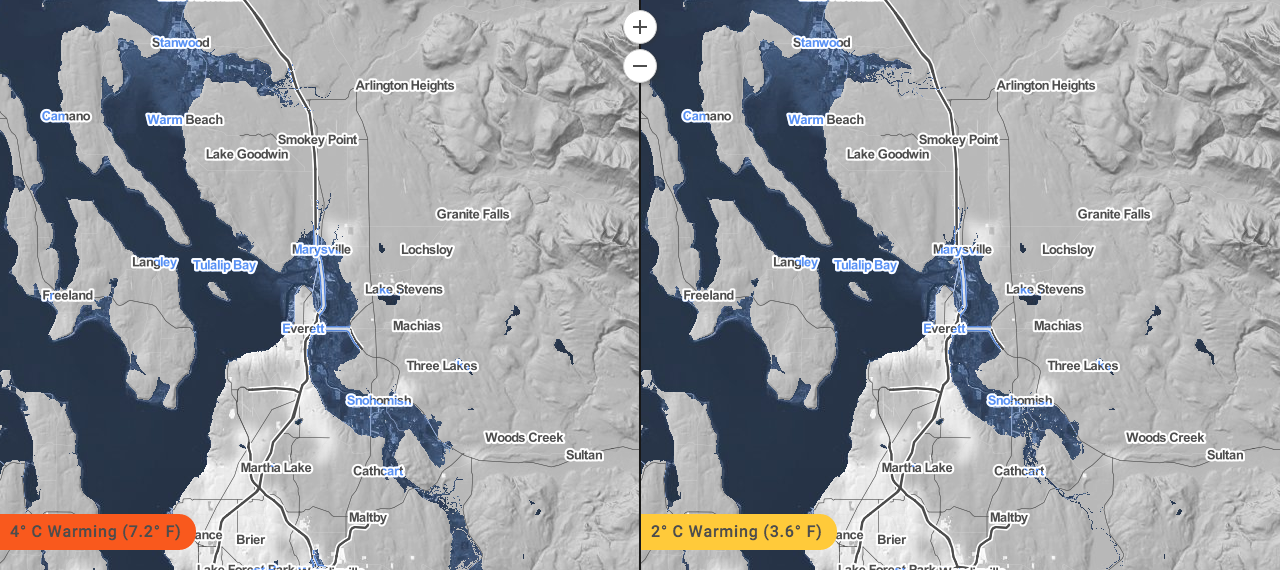

In fact, without significant change, we are on a path toward a 7.2°F global temperature change by 2100. Targets set by scientists and governments hope to greatly reduce global greenhouse emissions through this century in order to lower the lock-in of temperature change to a more modest 3.6°F increase. But even if we manage to succeed in a lower lock-in rate, the ramifications of global climate change will be huge. To simulate what this all means from a habitable and arable land standpoint, Climate Central created a series of maps to show different sea level rise scenarios. Their base scenarios pit the 3.6°F and 7.2°F temperature changes side by side with an outlook to 2200.

The Local Impact of Climate Change

The progressive change that sea level rise could have locally is obvious. Entire communities like low-laying Georgetown and South Park could be swept away. Pioneer Square could finally sink back into Elliott Bay. And even Seattle’s industrial economic engines south of Downtown — as widespread as the Green River Valley — could be permanently submerged. Only the freeways of I-5 and I-405 that once served them would remain, and that’s merely because they’re on higher ground.

Looking closer in at Seattle’s original settlement of Alki, that cherished neighborhood would get partially pulled back into the Puget Sound under the 3.6°F scenario. But it’s the 7.2°F scenario that’s especially astonishing. Hardly a block on the peninsula would remain, save for a few lucky homeowners that would get new waterfront property near the tip.

Dialing it back just a bit to 2050 and 2010, we can see that different rates of greenhouse gas emissions and temperature rise result in wildly different outcomes over the same time periods. If we went all-in globally to all but eliminate greenhouse gases, we would still be in for some inundation of Seattle and the region. Throwing our filth to the winds though would be catastrophic if not expensive to mitigate against, especially along much of the industrial Duwamish River.

But it’s not just industrial lands and a few neighborhoods near Seattle that could be stricken with mass inundation. The Port of Tacoma’s Commencement Bay operations could be in serious trouble, too. In both temperature scenarios, the port facilities could become increasingly submerged by higher waters. That’s bad news for the region. Few may know it, but the Port of Tacoma has a considerably higher traffic of goods moving in and out of the port facilities there than at the Port of Seattle. It would seem then that water-based shipment of goods could see a major change over the next century or two. As waters rise, local ports will simply have to move to higher ground or make higher ground at their current facilities. Regardless of how that is achieved, it will be a serious challenge and port authorities would be wise to consider how to adapt.

And yet, ports don’t live independent of the markets that they serve. As evidenced above, much of the Green River Valley and Puyallup River Valley where industrial and commercial activities are found today may not be there for the ports to support in the future. Indeed, those activities will likely need to move elsewhere, but it’s not clear where that is yet given the largely residential land use pattern that persists almost uninterrupted beyond them. And perhaps as our economy evolves with time, the progressive displacement of those activities will have little bearing on the overall function and economy of local business. But those are major unknowns and liabilities that ports and communities will need to sort out with time.

Perhaps the most important aspect to this all is the impact that agricultural lands will feel. People can move and people can adapt. Business can move and business can adapt. Agriculture can’t. Those lands thrive on river valleys that carve out space for quality soils. It happens through the undulations that result from the ebb and flow of river bows as they snake their way through rock to till the land. That process is long. Sea level rise will be much quicker and the land use pattern that it will meet as it rises will largely be incompatible. It’s not a matter of further moving people from the new water’s edge so much as a matter of nutrient-filled soils. You can’t just create amazing soils overnight, especially from areas that lack quality soil and were once paved over. Unfortunately, the true devastation will be exacted upon our increasingly diminishing and few lands for food and resource production.

But there are solutions that we can use in order to prepare our agricultural resources for these changes. Certainly, there are the things we are already doing like the research of more efficient ways to increase food production; many that are non-traditional practices. Public policy should be greatly enhanced to give protection to valuable agricultural lands and areas adjacent to them. And evaluating ways to prevent or reduce complete inundation of river valleys near coastal regions should be further explored.

Not A Forgone Conclusion

Mass inundation of the Puget Sound is only a forgone conclusion if we let it happen. It doesn’t have to be. Recognizing that likely climatic changes are on the way gives us time to critically consider what risks we should analyze, derive solutions that will meet them head-on, and put them into action. Humanity has an uncanny ability to constantly adapt to almost any situation. And we should have every reason to believe that humanity will be able to face these challenges with successful resolutions. But that work has to start now.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.