The Cascadian Region is formed from its very active, and occasionally violent, natural environment. It’s seismically active, floods, has land slides, and sometimes large waves inundate coastal areas. The past month has served a reminder of this fact. Rivers across the Puget Sound experienced major flooding in early December. Bluffs collapsed on the land below them. And just this past Tuesday, a 4.8 magnitude earthquake struck in the Haro Strait between Vancouver Island and the San Juan Islands.

Seattle happens to be susceptible to all of these hazards (and more). Recently, the City of Seattle published a comprehensive map service to explain where, why, and how natural hazards are likely to strike in the city.

The whole of the Pacific Coast is well known for earthquakes. They’re incredibly common occurrences due to plate tectonics, the slow movement of landmasses that can cause the earth to noticeably shake. In the Pacific Northwest, the Juan de Fuca Plate plays a major role in shaping our coastlines and geography. Hundreds of small earthquakes happen every year near the Cascadia Subduction Zone as the Jaun de Fuca Plate dives under the North American Plate; most of these go unnoticed because of very low magnitudes and their depth of occurrence. These earthquakes can happen anywhere along the local fault lines that emanate from the plates. Damage and severity of earthquakes are amplified along faults, although the effects of an earthquake are widely felt as ground waves radiate violently from an epicenter.

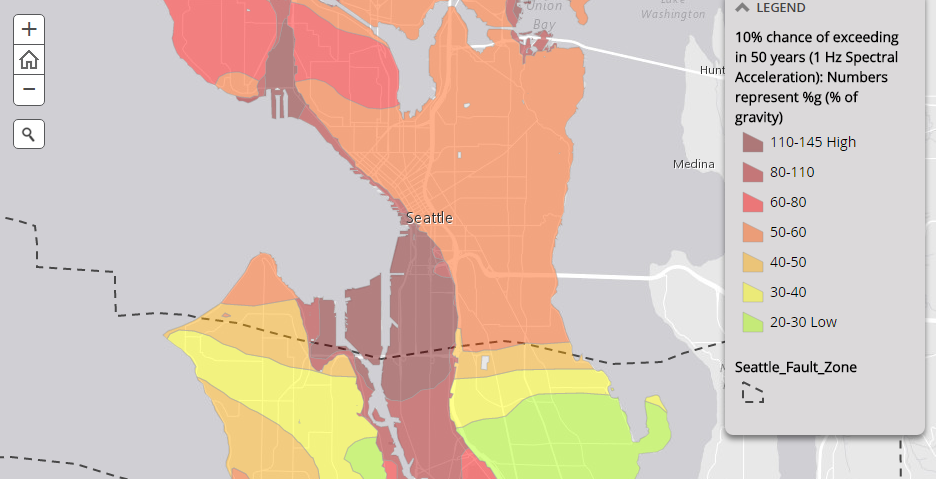

Seattle has the misfortune of a very local fault zone running through West Seattle, Duwamish industrial area, and Southeast Seattle. The Seattle Fault, as it is known, could experience an earthquake with a magnitude up to 7.5. While all areas of the city will feel a significant earthquake if it hits the region locally — whether on the fault or not — the level of ground shaking will differ greatly depending upon location and geology. In regards to the map above, the data represents the kind of ground force that the city can expect in a given earthquake event, and is explained by the City in this way:

…[T]hese maps show the amount of earthquake-generated ground shaking that, over a specified period of time, is predicted to have a specified chance of being exceeded. Ground shaking caused by earthquakes is often expressed as a percentage of the force of gravity. For example, the seismic hazard map…shows the percentage of the force of gravity that has a 10% chance of being exceeded in 50 years. Based on such a map, if you were living in the same house for 50 years, and that house was in a zone labeled “20% g”, then there would be 1 chance in 10 that (at some point during those 50 years) an earthquake would shake your house at a level of at least 20% of the force of gravity.

To appreciate why these values of ground shaking are expressed as a percentage of the force of gravity, note that it requires more than 100% of the force of gravity to throw objects up in the air. In terms of felt effects and damage, ground motion at the level of several percent of gravity corresponds to the threshold of damage to buildings and houses (an earthquake intensity of approximately V on the Modified Mercalli scale). For comparison, reports of “dishes, windows and doors disturbed” corresponds to an intensity of about IV MMI, or about 1.4% – 4% of gravity. Reports of “some chimneys broken” correspond to an intensity of about VII MMI, or a range of 18% to 34% of gravity.

Needless to say, areas like Interbay, Pioneer Square, the Duwamish industrial area, and even Magnolia and Queen Anne hills present serious risks to anyone within them during a major earthquake event.

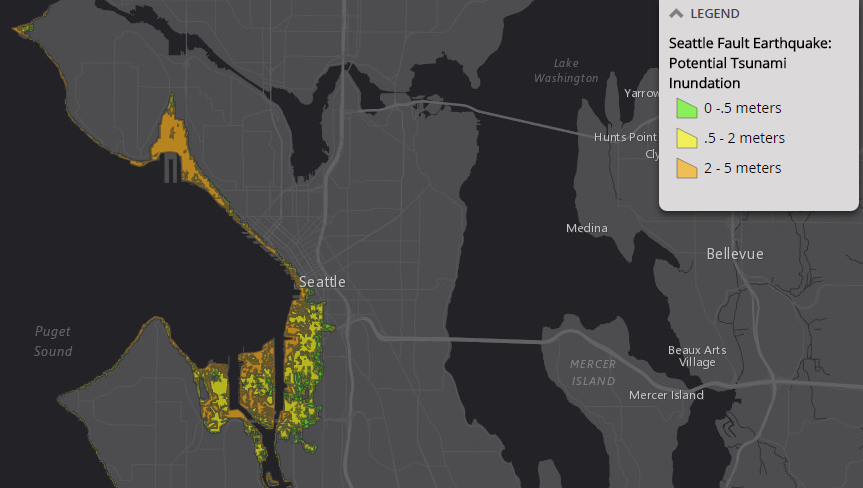

Surprising as it may be, Seattle is susceptible to tsunamis, but not from the Pacific. Due to the the shape of the Salish Sea and coastal landmasses of the Washington Coast and Vancouver Island, Seattle is fairly safe from any major tidal action associated with a Pacific Ocean tsunami. But the city is at risk from localized tsunamis. A major earthquake on the Seattle Fault could generate a tsunami in the Puget Sound and affect some shoreline areas of the city. Seismologists created a model using a 6.7 magnitude earthquake on the Seattle Fault — a very likely maximum magnitude on the fault in the near future — to see what extent of tsunami action could result. What they found is what you see above. Areas on the Elliott Bay could experience up to 5 meters (16 feet) tsunami, although the number is likely considerably lower. Pioneer Square, Interbay, and the Duwamish industrial area are the mostly like locations to experience the brunt of a localized tsunami.

For a bit of perspective, it’s worth noting that Seattle has experienced a tsunami before, but it was many centuries ago. Research has shown that one tsunami event was generated by a 7.5 magnitude earthquake on the Seattle Fault somewhere around 900 C.E. That magnitude is very likely the maximum expected on the Seattle Fault, but the chances of that occurring are incredibly small (about 1:5,000 in any given year)

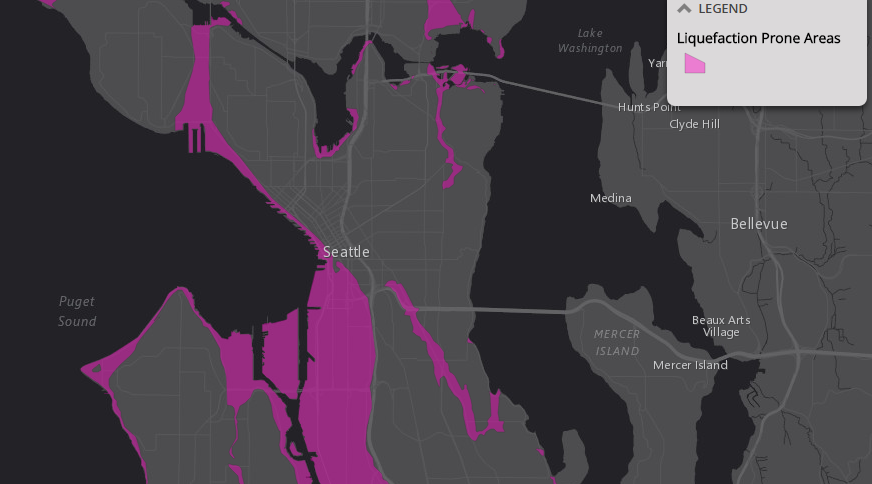

Large swaths of Seattle are prone to liquefaction. Buildings that are built upon liquefaction zones could sink, topple, or even be overturned during an earthquake event. That’s because soils in liquefaction zones typically consist of sand, silt, and gravel that are highly saturated with water. The shaking of ground can cause the solid sediments to then separate and liquify (think quicksand). It’s also common for the soils to create muddy flows that spread laterally; this can cause extensive damage. Liquefaction zones tend to be found closest to waterbodies, and often those that have been filled in.

Many may be familiar with Seattle’s major regrades in the early 20th century. Those efforts resulted in sluicing of hillsides and the dumping of fill into Elliott Bay and the Duwamish estuary. They also happened to provide for the massive expansion of Pioneer Square and the Duwamish industrial area. Naturally, the latter are at high risk of liquefaction. In the 2001 Nisqually Earthquake, Pioneer Square experienced the worst damage from the 6.8 magnitude earthquake, and perhaps the region due to minor liquefaction. Other areas of Seattle also are at risk like Interbay, certain stream corridors, and the edges of shorelines.

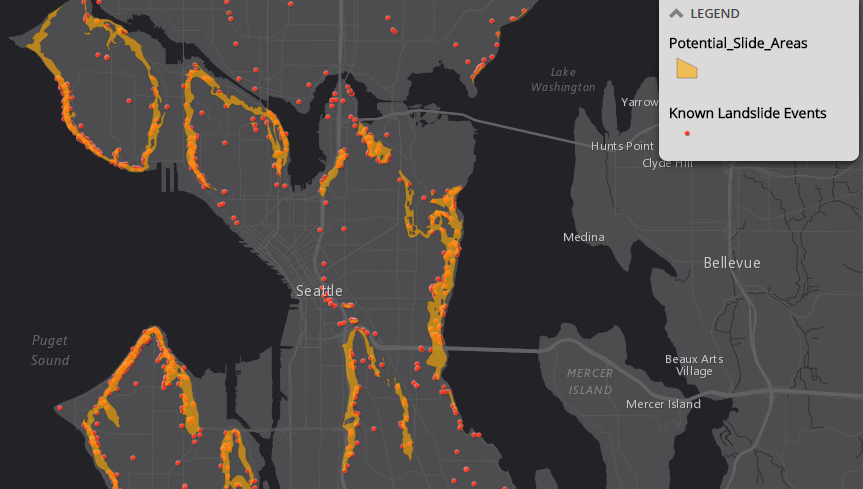

Built upon seven hills, Seattle has some steep geography. Queen Anne, Magnolia, Beacon Hill, and the central hills of Capitol Hill and First Hill offer plenty of evidence of that. Heck, many of them have “hill” in their name! Hills and saturation from rain don’t mix well. Very often during wintertime, landslide events are prevalent in Seattle. These can happen anywhere on a slope, but most typically are the result of shallow slides on sloping topography; debris commonly sluffs on down the hillside, but it’s not always seriously dangerous.

But more seriously, 18%+ of all landslides in Seattle are the result of deep-seated landslides where where whole chunks of land will slide to the toe of a slope. Given Seattle’s dense development pattern, this can come with serious consequences. Buildings and structures can collapse or even be crushed through landslide events. The City estimates that at least 8.4% of the land in the city qualifies as landslide prone.

Looking at the map above, coastal areas where bluffs are common and the back sides of Queen Anne and the central hills exhibit the highest concentrations of landslide events.

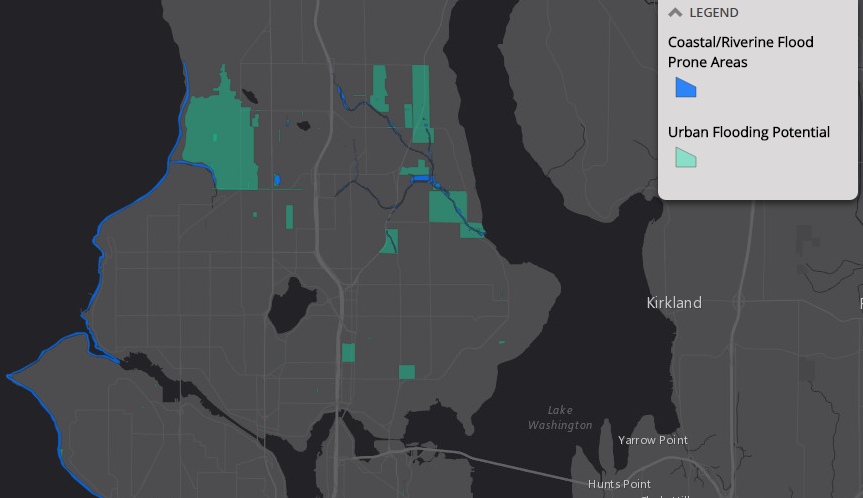

Seattle tamed much of the natural environment early on its city-building days. Wetlands were removed, streams covered or realigned, hilly features regraded, and damming waterbodies. So in many ways, Seattle has removed risks to series floods aside from temporary flooding of street in intense downpours. Still, Seattle is a city built around water, and because of this is at occasional risk of coastal flooding, localized river flooding, and problem spots for major urban flooding.

Lake Washington, Salmon Bay, and Lake Union are fortunately managed by the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks, which release water as needed. The risk of flooding is minimal at worst along those waterbodies. But, some small streams like Pipers Creek through Carkeek Park can and do cause flooding. This is particularly a problem to the blocks north of the creek that experience localized flooding. Major tidal events, like King tides, can also cause shoreline flooding along the Puget Sound. And though the risk is low, the Duwamish River is supplied by the Green River. Halfway to the source of the river, roughly Kanaskat, is the Howard A. Hanson Dam. There is a very real possibility that the dam could fail1, which would result in extensive lowland flooding along the river valley and Duwamish.

Footnotes

- The Howard A. Hanson Dam did undergo recent improvements due to seepages found in the dam during 2009.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.