Impact fees have been on the radar in Seattle for many years now. The city is the largest jurisdiction in the state to forego collection of transportation impact fees on new development, despite authority to do so. To right this wrong, the Seattle City Council issued a Statement of Legislative Intent in November 2017 to begin the process of looking at the issue anew. In doing so, Council Central Staff took over the reins from the executive branch, which let the issue languish for several years after completing a white paper.

How Transportation Impact Fees Could Be Imposed

Last March, the Seattle City Council was briefed on transportation impact fee options. Kendra Breiland of Fehr and Peers laid out the framework and possible policy choices before the city council. “First and foremost, the program should be structured to fund projects that align with Seattle’s values,” she said. “A piece of that is really funding innovative projects. So, thinking about projects that really address Seattle’s values, thinking about Greenway projects, thinking about off-board fare payment.”

Breiland pointed to many of the transportation projects to be funded through the Move Seattle Levy as good candidates for impact fees funding. Broadly speaking, she said that impact fees could directly facilitate a host of progressive transportation improvement priorities in the city, including:

- Sidewalk expansions and gaps in the pedestrian network within right-of-ways. That means that impact fees could be focused on efforts to improve pedestrian access to transit facilities, advance many Safe Routes to School projects, and provide equity to areas that have long-missed out on sidewalks in the north and south ends of the city.

- New bicycle infrastructure which could realize many aspects of the Bicycle Master Plan, such as the Basic Bike Network, Neighborhood Greenways, and general bike facility capacity improvements.

- Transit improvements in the right-of-way, such as transit signal priority, off-board fare payment, bus lanes, bus stops, and other transit improvements within streets. Operational and added equipment to fleets, however, would not be eligible for impact fee funding.

- Strategic freight improvements throughout the city.

- Lastly, rails-to-trails corridors like the Burke-Gilman Trail which are considered a right-of-way under state law and therefore are possible transportation facilities eligible for strictly pedestrian and bicycle investments.

In terms of how a program could be structured, Breiland suggested that past discussions focused on a citywide program instead of by subareas. A wider structure could allow investments to be made flexibility throughout the city if predicated on a large project list. Such a project list could still be equitably designed to ensure that projects funded by the impact fee program are targeting areas in need with high priority improvements.

There are clear differences in transportation demand across the city, Breiland noted. Trips in Downtown Seattle in and urban centers and urban villages tend to have much higher rates of walking, bicycle, and transit trips in contrast to less dense areas of the city than have higher rates of private vehicle trips. Structuring an impact fee program in response to this could mean imposing varying impact fee rates by geographic area, with lower rates where private vehicle trips are lowest and access to transit is higher, for instance.

Any impact fee program will need to involve a proper rate study to determine the kind of transportation demands that specific land use types generate. Typically, transportation impact fees are imposed on the basis of the number of afternoon and evening peak-hour trips assumed to be generated by a development. Once the rate study is completed, the city could go through the process of compiling an actual fee schedule based upon several considerations: use type and transportation demand, cost of capital improvement on project list, geographic location, and other relevant policy issues.

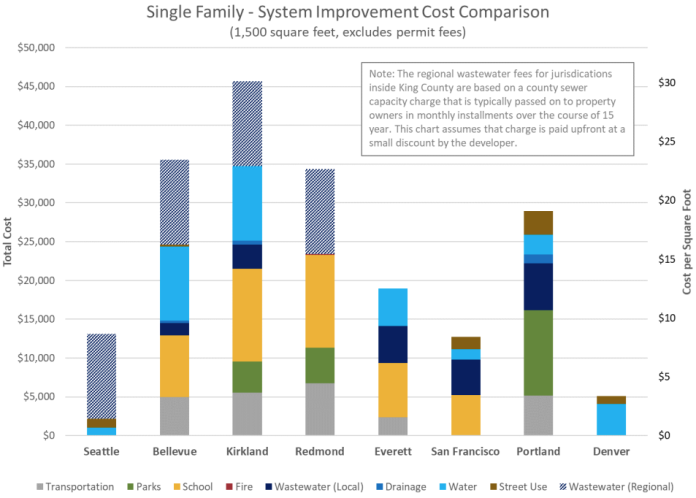

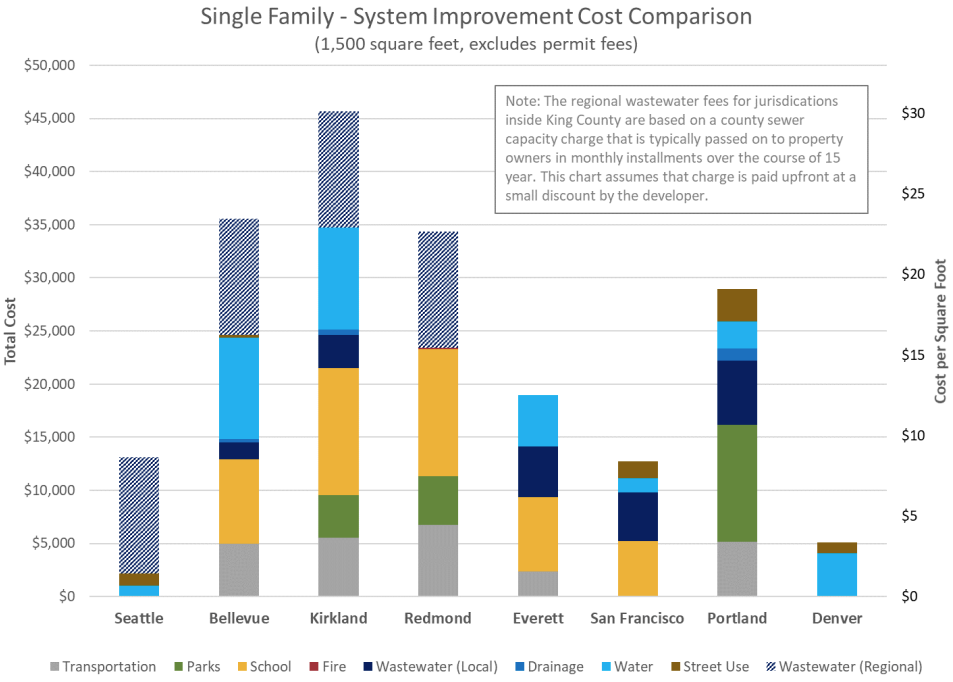

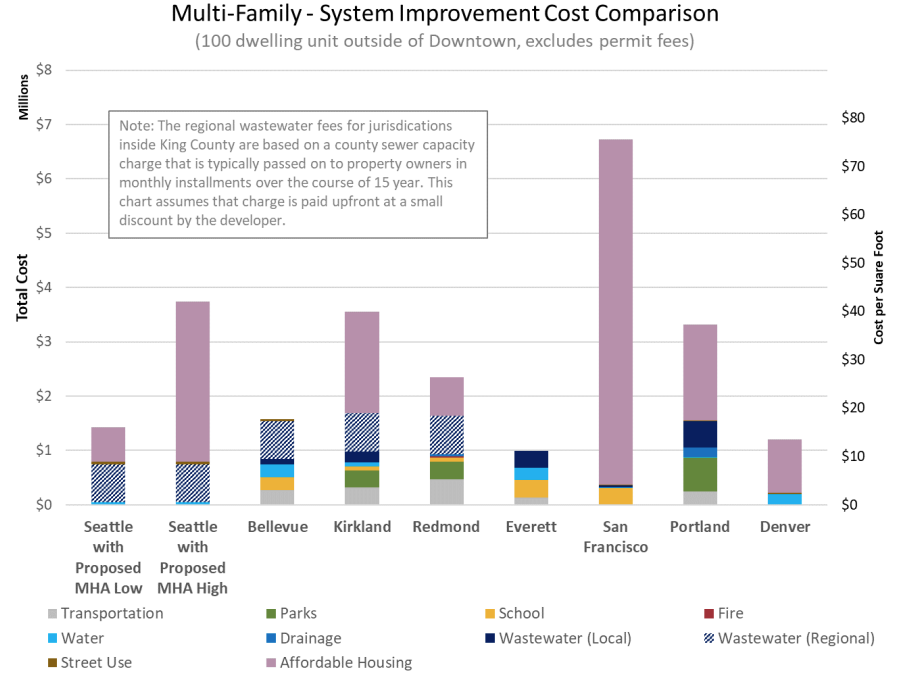

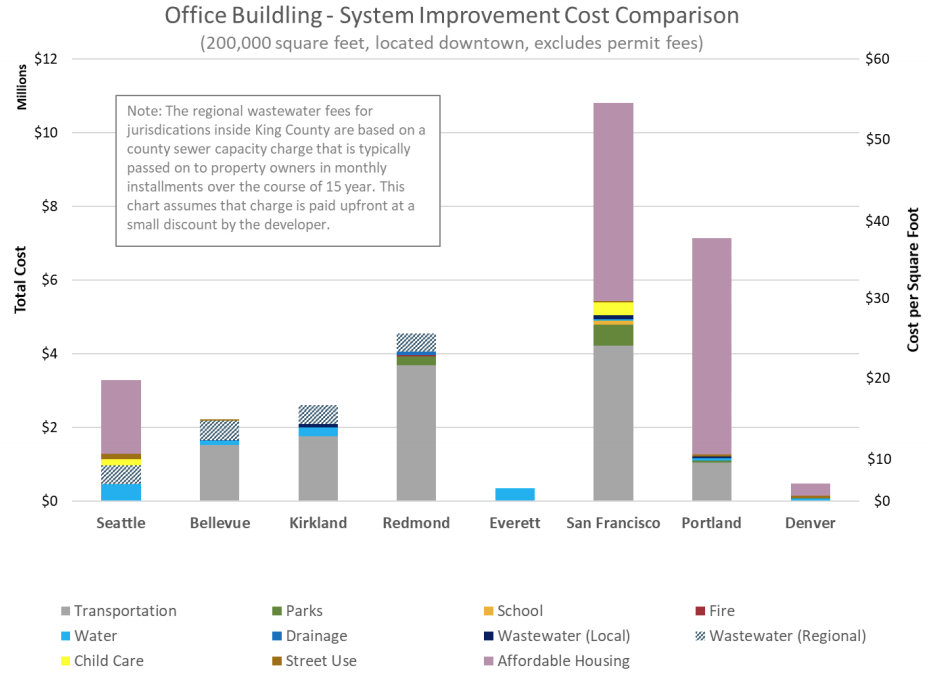

Transportation impact fees are just one part of overall system improvements (e.g., parks, emergency service facilities, child care, affordable housing, and water and sewer connection contributions) that developers are often responsible. Looking at the wider range of obligations, Breiland highlighted how Seattle compares to peer and regional cities when it comes to a range of system improvement types. She illustrated this through three hypothetical development scenarios (e.g., medium single-family home, large multifamily development, and large office development) and their system improvement responsibilities. Seattle stacks up toward the lower-middle of the pack and at the very bottom for single-family homes when excluding sewer connections.

On average, peer cities are imposing transportation impact fees under $5 per square foot for residential development. Meanwhile, commercial development typically is subject to much higher impact fees, ranging from about $10 to $25 per square foot where they are imposed.

Lastly, an important caveat that Breiland covered in her discussion is how impact fees could be collected for completed improvement projects. This may be desirable for the city to help free up revenues for other programmatic work that would not otherwise be available if impact fees were not still being collected to fund completed projects. There is a limitation here, however, in that it must be demonstrated that completed projects are continuing to provide capacity for future growth. Most jurisdictions, however, do not use this method instead opting to only impose impact fees on developments for projects yet to be completed.

How Seattle Is Considering Adoption of Transportation Impact Fees

Will Seattle finally move toward implementing impact fees? It appears a real possibility, judging by draft legislation under consideration by the city council. It would make several critical changes to enable imposition of transportation impact fees, including:

- Adoption of amendments to the comprehensive plan. A new goal would be added to the Transportation Element. “Base transportation impact fees on the difference between the value of the existing transportation system and the cost of identified capacity-related improvements needed to address the impacts of growth,” the draft goal reads. An amendment would also clarify the city’s intent to use transportation impact fees, rather than just consider them.

- Modify the transportation appendix. The comprehensive plan contains an appendix related to transportation. This would be updated to specify eligible projects for which impact fees could pay for and the methodology by which impact fees could be imposed. The draft indicates that the city would use the “existing system value methodology” to impose impact fees.

The “existing system value methodology” looks at existing deficiencies in the transportation system by calculating both the value of existing infrastructure and the value of land within city right-of-way. Once this value is derived, the number of current afternoon and evening peak-hour trips per person is determined and divided into the existing system value. This provides the existing system value per person per trip. Using this as a baseline, the city can determine the needed system improvements above this based upon a project list that will serve future development over a 12-year period and apportion the appropriate impact fee costs to be paid per trip that new development will create.

In keeping with the city’s desire to prioritize sustainable transportation, the project list to be funded by impact fees is narrowly tailored to transit, walking, biking, and freight programs. A draft map has been created, depicting where corridor projects could be implemented.

Transit improvements identified on the draft project list, include:

- The Graham Street Station, an infill station project on the Central Link light rail line;

- The Roosevelt RapidRide corridor between Northgate, Ballard, and Downtown Seattle;

- The Madison Street RapidRide G Line corridor between Downton Seattle and Madison Valley;

- The Route 44 corridor between Ballard and Montlake Triangle; and

- Fauntleroy Way SW and California Ave SW where the RapidRide C Line operates.

The draft project list also highlights implementation of the Bike Master Plan and Pedestrian Master Plan, in addition to several complete streets projects to benefit transit, waling, and biking. This includes a variety of key corridors like Aurora Avenue, Delridge Way SW, Rainier Avenue, N Greenwood Ave/N Phinney Ave, and Lake City Way. Projects from the Freight Master Plan would generally be eligible on the project list, though specific corridors are identified in the Duwamish Industrial District.

A public hearing on the proposal is scheduled today and could be adopted late this year. In tandem with the comprehensive plan amendments, a formal impact fee schedule should be forthcoming in the months ahead, which would be adopted with the comprehensive plan policy changes. That could include a variety of policy choices on how the fees are designed and whether credits could be applied by geography.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.