Called “Run-of-the-Mill NIMBY” in Court, Delays Mount As Existing Condos Sue for Views.

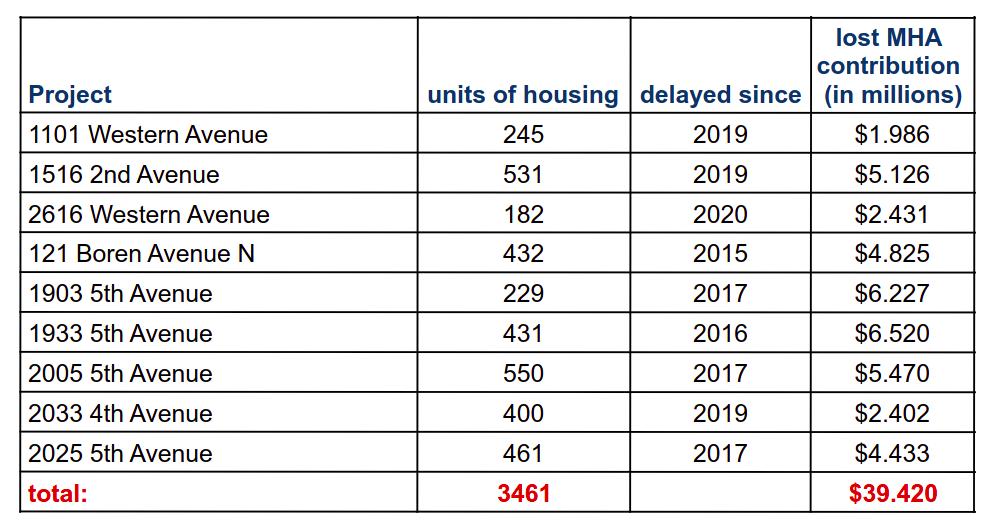

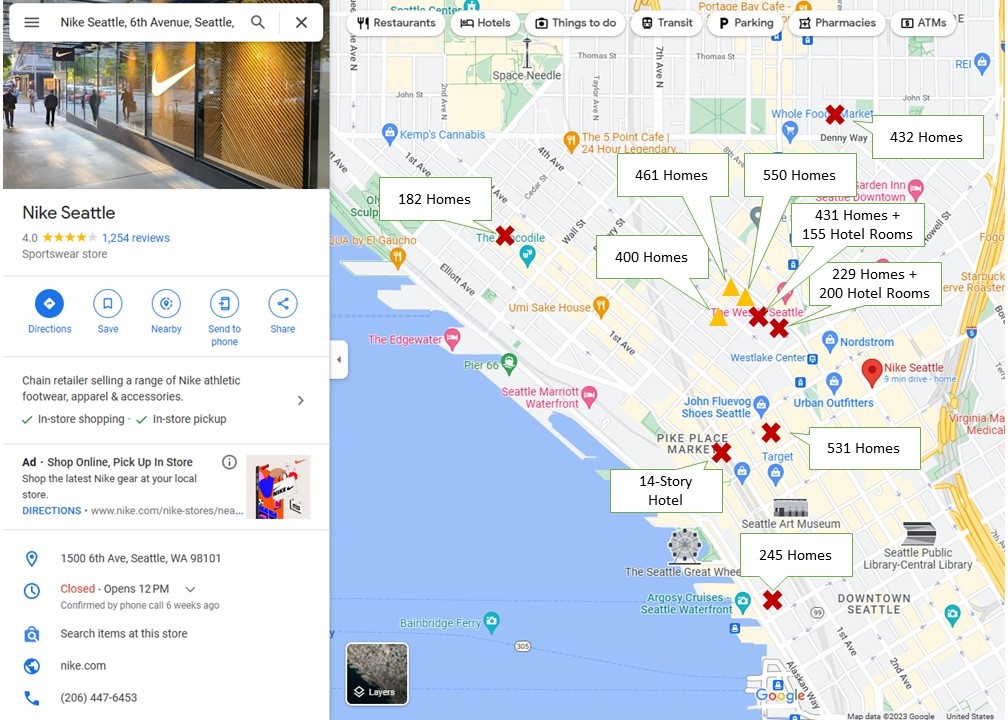

Using lawsuits and an aggressive opposition campaign in Seattle’s design review process, a small group of condominium owners has delayed construction of more than 3,000 units of housing downtown — and blocked $39.4 million in funding for the city’s affordable housing efforts.

An analysis by The Urbanist found that nine major housing developments in the downtown core have been stalled in design review, appeals to the hearing examiner, and lawsuits. All nine projects, if completed, would add significant contributions to the city’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program — ranging from $2 million to $6.5 million per project.

One of the most active opponents to these new apartment projects is the association of condominium owners at Escala, a 31-story luxury tower built in 2010 at the intersection of Fourth Avenue and Virginia Street. In the past year, the Escala homeowners’ association has filed several lawsuits and appealed decisions by the Seattle Department of Constructions and Inspections (SDCI). It has aggressively commented in design review hearings for years, going so far as to hire a communications consultant, Megan Kruse, who frequently makes written and verbal comments on neighboring projects.

Kruse, who is not a resident of Escala, but has lived downtown for more than 40 years, told The Urbanist her client isn’t opposed to all nearby tower projects, but rather wants developers to mitigate impacts such as competing alleyway access, delivery and garbage truck traffic, and the loss of light to surrounding buildings.

“There are no guaranteed views,” Kruse said in a phone interview. “You can’t be the last one on the block. But everything should be weighed and balanced when it comes to the cumulative impacts. If you’re going to build this really huge 1,000-person building and not include a loading berth, there’s something wrong with that.”

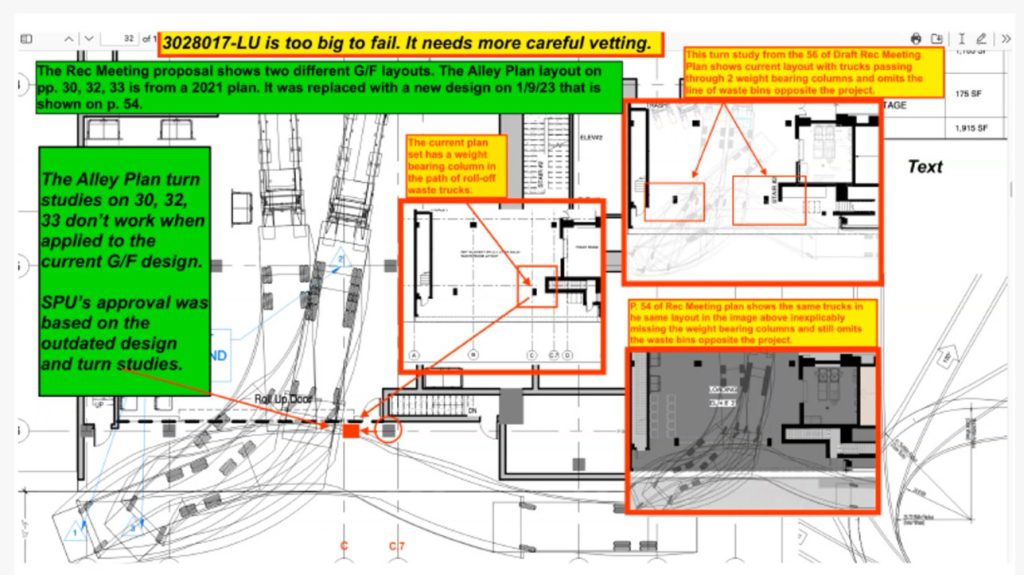

The project Kruse was referring to is a proposed 44-story, 550-unit apartment building at 2005 5th Avenue, across Virginia Street from Escala. During a design review meeting about the project on Tuesday evening, Kruse made comments taking issue with what she said were insufficient facilities in the alley for deliveries and garbage pickup. She presented a variety of slides asking for a redesign, citing a list of dangers ranging from national freight-related injury statistics to the climate impacts of delivery vans.

In its deliberations, the downtown design review board rejected Kruse’s criticisms, and voted unanimously to move the project forward.

Escala has also raised the issue of delivery trucks in design review comments and lengthy email correspondence with SDCI Director Nathan Torgelson regarding another nearby project, a 44-story tower with 461 apartments at 2025 5th Avenue.

When asked to comment on delay tactics in the design review process, SDCI spokesperson Bryan Stevens wrote in an email, “[Design review] is not intended to be a vehicle for delay, but some may use it to challenge issues beyond the basis of a decision to cause delay or invoke a settlement. Our staff work to file motions for dismissal of appeals deemed to be erroneous or without merit.”

SDCI is currently holding a stakeholder review of the design review process and will make its recommendations soon, Stevens said. He said Mayor Harrell and Councilmember Dan Strauss are awaiting those findings before introducing legislation that would reform the design review process, including exempting design review from affordable housing projects or projects that contribute to the MHA fund. Also proposed in the legislation is a two-year pilot program allowing all multifamily housing projects to select internal SDCI administrative review over design review.

Brady Nordstrom, coordinator for Seattle For Everyone, said in an email to The Urbanist that “we believe that it’s time to fix Seattle’s design review as a specific bottleneck in the housing pipeline. Design review has become slower and more unpredictable in recent years.”

Twitter user @asher_971 drew attention to the delay issue in January, writing in a post about the stalled tower projects: “that’s hundreds of construction jobs, millions in MHA payments, and thousands of residents + potential shoppers + foot traffic blocked over concerns about historic preservation, views, lighting, noise, parking, and traffic.”

In addition to making comments, Escala hasn’t been shy about taking the city to court to oppose neighboring projects. It filed lawsuits against two proposed nearby developments at 1903 5th Avenue (a hotel-apartment complex with 229 units of housing) and 1933 5th Avenue (a hotel-apartment complex with 431 units of housing). The two projects, which have been stalled since 2016 and 2017, would together make an estimated contribution of $12.75 million to the city’s MHA program if built.

In December, the Washington state supreme court refused to hear both of Escala’s lawsuits against the two projects on Fifth Avenue. In a bracingly strong statement from the Seattle city attorneys arguing the case, they wrote, “Escala again failed to demonstrate any substantial public interest in their run-of-the mill ‘Not In My Backyard’ (‘NIMBY’) claims.”

Escala’s lawyers moved to strike that language from the court record, but the judge denied this request.

Arguing against the project, Escala’s attorneys claimed that shadows from the new buildings would result in “cancers, cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders and mental health [sic].” The court rejected those claims, largely because of state legislation passed in 2022 that limits the use of State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) challenges to housing projects based on concerns over aesthetics and light — in addition to provisions passed in 2019 limiting appeals based on traffic impacts.

Meanwhile, a bill moving forward in the legislature introduced by Representative Amy Walen (D-48, Bellevue) would ban design review for housing projects statewide.

“Problems with design review have recently become more well-known as evidenced by the multiple state bills seeking to reform the process,” Nordstrom said in an email. “We are enthusiastic about the growing public and political will to fix design review to be more inclusive, predictable, and efficient.”

In one of the cases before the state supreme court, city attorneys gave a shout out to the new state law limiting SEPA appeals: “In June 2022, at the urging of advocates who described how meritless SEPA appeals had delayed sorely needed housing projects, the legislature expanded the exemption to bar appeals based on alleged impacts to aesthetic and light as well.”

Escala isn’t the only opponent of new apartment towers downtown. In October, residents of the Madison Tower at 1000 First Avenue and the Seattle Historic Waterfront Association filed a lawsuit against the city, challenging a 17-floor, 245-unit apartment building replacing a surface parking lot at 1101 Western Avenue. The project would add nearly $2 million to the city’s MHA affordable housing coffers.

In August 2022, a group called the Belltown Livability Coalition filed an appeal against a Master Use Permit the city granted to a proposed 19-story, 181-unit apartment building at 2616 Western Avenue. The group’s website complains that the project, which would add $2.4 million to the city’s affordable housing fund, would end up “cluttering our skyline, cutting off light to the surroundings [sic] buildings, and modifying our city plan without our input.”

And condo owners in Fischer Studio, a 28-unit historic building constructed in 1918, have filed an appeal against a 46-story, 531-unit apartment tower at 1516 Second Avenue.

It turns out Megan Kruse lives at Fischer Studio and has, not surprisingly, been very active in opposing the project.

Attorneys for Fischer Studio, in their appeal to the hearing examiner, claimed the nearby apartment tower would impact neighbors “through the nearly complete elimination of natural daylight in private residences, health impacts associated with loss of light, loss of privacy, loss of air quality, wind, and safety impacts associated with the proposal’s overuse of the alley, which will likely interfere with access, emergency response efforts should they arise, and put the health, life, and safety of residents of the Fischer Studio Building in jeopardy.”

In her interview with the Urbanist, Kruse echoed these dire concerns. “So there’s people going to be staring at our bedroom and living room windows 16 feet across the alley,” she said. “We had a study done, and 40% of the units will have the amount of light available in a movie theater, 365 days a year.”

Developers of the nearby tower, which was originally proposed in January 2019 before the onset of the pandemic, have guided the project through four years of design review, an appeal to the hearing examiner and a lawsuit from Fischer Studio. The project, if completed, would add $5.125 million to the city’s affordable housing efforts.

On Wednesday, February 21, the Washington state court of appeals rejected Fischer Studio’s suit, largely based on the new state law limiting SEPA challenges. The judge also observed that Fischer’s complaints about Seattle’s guidelines not being applied strictly had little legal merit, noting: “The ‘guidelines’ are not ordinances. They are not rules regulating the improvement, development, modification, maintenance, or use of real property. Fischer does not identify any law that requires the enforcement of the guidelines.”

For her part, Kruse would like the city to have even more stringent guidelines. “I think the reason there are all these challenges is because there are no firm rules. There are no standards that people can rely on,” she said, arguing that city residents want more assurances. “So that I’m not going to be all of a sudden living in a basement apartment because somebody decided not to be nice.”

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.