The Washington State Legislature is hotly debating where and how to allow multiplexes in more areas via HB 1110 and its companion SB 5190. The missing middle housing legislation is tailored to only apply in cities planning under the Growth Management Act and meeting specific locational or size criteria. That still covers a large proportion of Washington cities, but there’s a lot of hoopla over real and imagined density and compatibility concerns and the scope of the legislation has been pared back some.

A big question weighing on the debate is how much additional housing the legislation would actually create. Opponents paint it as a developer giveaway that may end up backfiring and worsening the housing crisis. Proponents argue it would unlock a new tool in housing production and provide a major boost to housing production and equitably distributing new housing where it’s currently off-limits. The Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) recently tried to answer this question of just how much housing HB 1110 would allow for their jurisdiction in King, Snohomish, Pierce, and Kitsap Counties.

In a small data brief, PSRC used its extensive modeling tools to issue a very detailed data analysis by looking at different factors the legislation could have on development capacity and likely development. The numbers initially seem very big when walking through the analysis, but the actual amount of housing output is a comparably small share of parcels zoned for residential use.

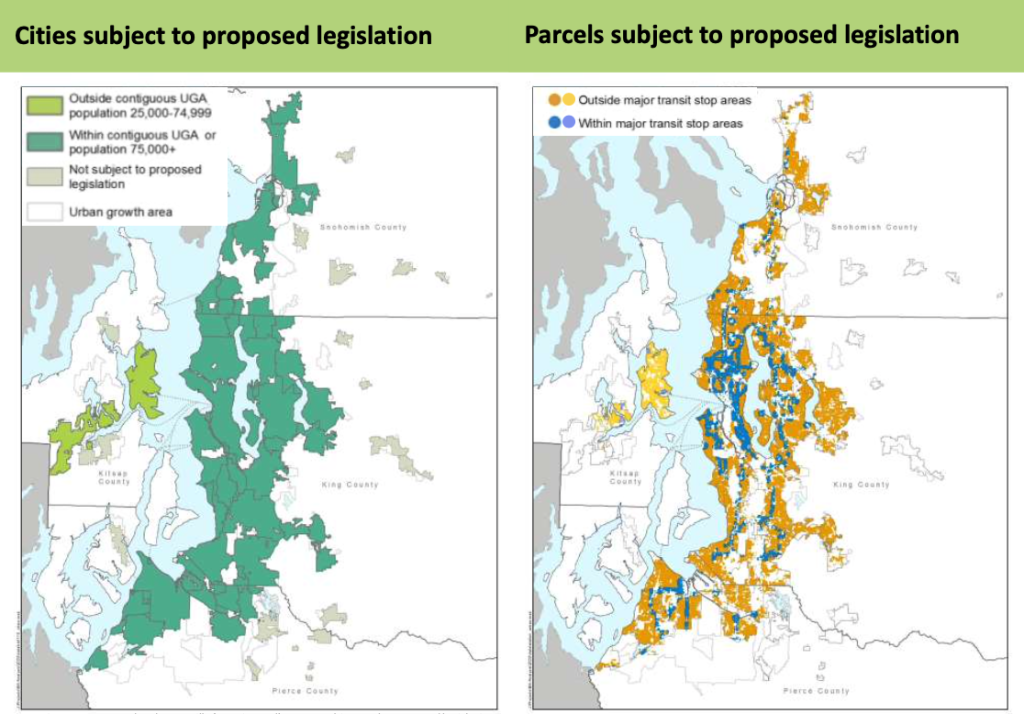

According to the analysis, the four-county region has 1,302,000 parcels of land with 771,000 potentially subject to the proposed legislation. Of that number, 747,000 parcels currently allow residential use and 666,000 of those parcels currently do not already meet the proposed zoning regulations. There is a split in how the legislation would treat areas within and outside a half-mile of major transit stops for development potential. Breaking those out separately, PSRC estimates that 164,000 parcels are within major transit stop areas and 502,000 parcels are outside of them.

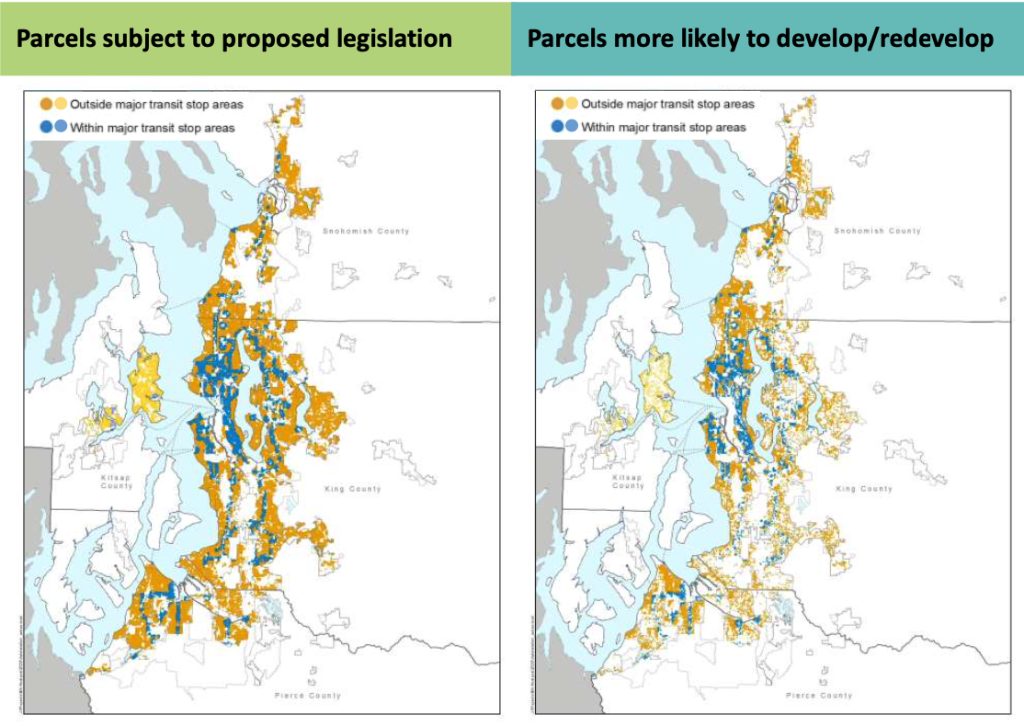

The PSRC analysis assumes environmental constraints and that land is really only developable if it is at least 2,500 square feet. That leaves about 616,000 parcels of developable land and 592,000 developable parcels that are either vacant or currently only have one dwelling. Looking at market factors, PSRC estimates about 110,000 parcels (28,000 parcels within major transit stop areas and 82,000 parcels outside of them) are likely to actually see development under the legislation.

Given all of this, PSRC makes further assumptions, including how much net new development capacity the legislation could create and how many actual homes might get built, based upon the various factors.

- The net new development capacity is about 2,309,000 homes (828,000 homes within major transit stop areas and 1,481,000 homes outside of them); and

- The number of homes that actually might get built is a mere 206,000 homes (84,000 homes within major transit stop areas and 122,000 homes outside of them) over the next 20 years.

That 206,000 homes number might seem big to some, but it’s considerably less than the number of net new homes the region needs to produce in the next decade alone.

The data does visualize where missing middle housing development is likely to happen. That is heavily centered on Seattle through cities in Southwest Snohomish County. Tacoma to Lakewood likely see clusters, as well as parts of Everett, Lake Stevens, Marysville, and Arlington. Pierce and Snohomish Counties have a lot of urban unincorporated areas and Kitsap County cities tend to be small, so the overall effect of the legislation isn’t so great in them otherwise. As for cities in South and East King County, the legislation has a modest impact compared to Seattle, Shoreline, Burien, Tukwila, and SeaTac.

Because of the rapidly-evolving nature and harder-to-quantify aspects of the legislation, PSRC’s analysis doesn’t yet account for a newer provision in the legislation that allows higher missing middle housing densities near “community amenities.” These features are put on equal footing to major transit stops and include public schools, common schools, and any entrance to a public park operated by a local or state government. So that could mean that the legislation would facilitate and realize higher levels of missing middle housing development, but it also could be a wash in the end. As the legislation moves the through legislative process, state lawmakers are all but sure to reduce the legislation’s impact in other ways.

Regardless, the PSRC’s analysis suggests statewide middle housing reform would add something in the ballpark of 200,000 extra homes in Puget Sound over the next 20 years, which are sorely needed to address the dire shortfall of homes and affordability crisis.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.