On Thursday, Urban Institute released a new report focused on the Seattle metropolitan region that is sure to be of interest to urbanists and housing advocates. The Urbanist published a preview of this research this fall, after talking to lead researcher Yonah Freemark. The full report goes into much more detail about housing needs in the Puget Sound region and the potential impact of loosening zoning restrictions, particularly near frequent transit.

“Our analysis shows that the region is on track to add fewer housing units than it needs to match expected population growth by 2050,” the researchers wrote. “The Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) estimates a need for about 275,000 new housing units in the region over the next decade — about a third more than were added during the 2010s. Although current zoning policies provide room for additional housing growth near transit, much of that potential is in communities where real estate development demand has been limited in recent decades; on the other hand, many jurisdictions with high development demand have very little room for new homes, inhibiting new construction.”

Seattle was the third-fastest growing metropolitan region in the country in the 2010’s, the authors note, trailing only Austin and Fort Worth, Texas. Without zoning changes and other interventions, it appears housing growth will continue to lag population growth with disastrous implications for housing affordability, homelessness, and a whole host of other related issues.

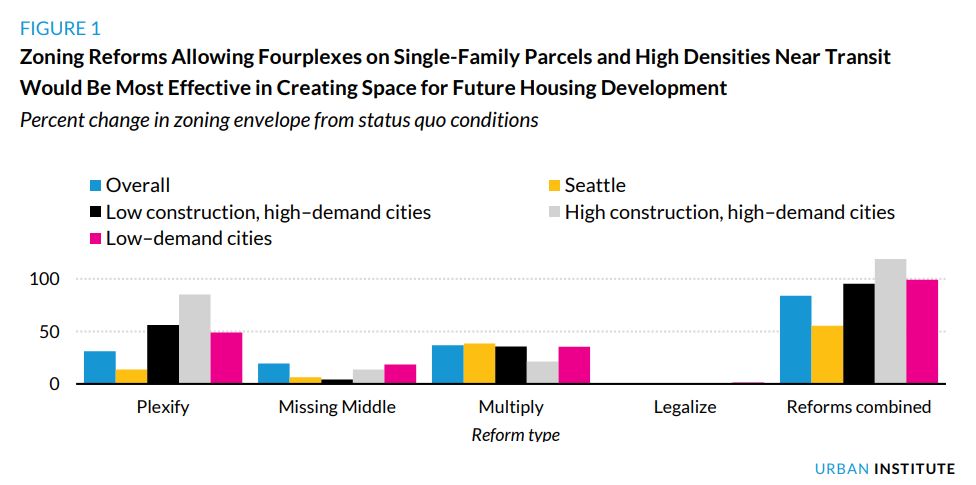

The report analyzes zoning city by city and quantifies the amount of housing that zoning liberalization would allow. The modeled zoning reforms are focused on frequent transit corridors, also studying a “plexify” option to add fourplexes elsewhere. The clear takeaway is that existing zoning is quite restrictive and is smothering new housing in high demand cities from Seattle and Bellevue on down to smaller cities.

“While some municipalities have added substantial new housing supply, especially near existing and planned transit stations, others — including areas with high housing values such as Bellevue, Lake Forest Park, Mukilteo, and Newcastle — have added very few, despite considerable market demand; these communities also feature few federally subsidized affordable housing units,” the report concludes. “Even in Seattle, where most transit-adjacent housing growth is concentrated, many station areas are zoned for low densities by right.”

Reached by phone, Freemark underscored the mismatch between the Seattle region’s zoning capacity and the location of many of its high-demand housing markets.

“There actually is significant room in the existing zoning to build more housing units,” Freemark said. “The problem is that a huge percentage of that increased space for more homes is specifically in areas that are unlikely to attract developer interest… So you have places like Everett where there’s actually a lot of zoning enabling lots of housing construction but not a lot of developer interest in actually building those houses.”

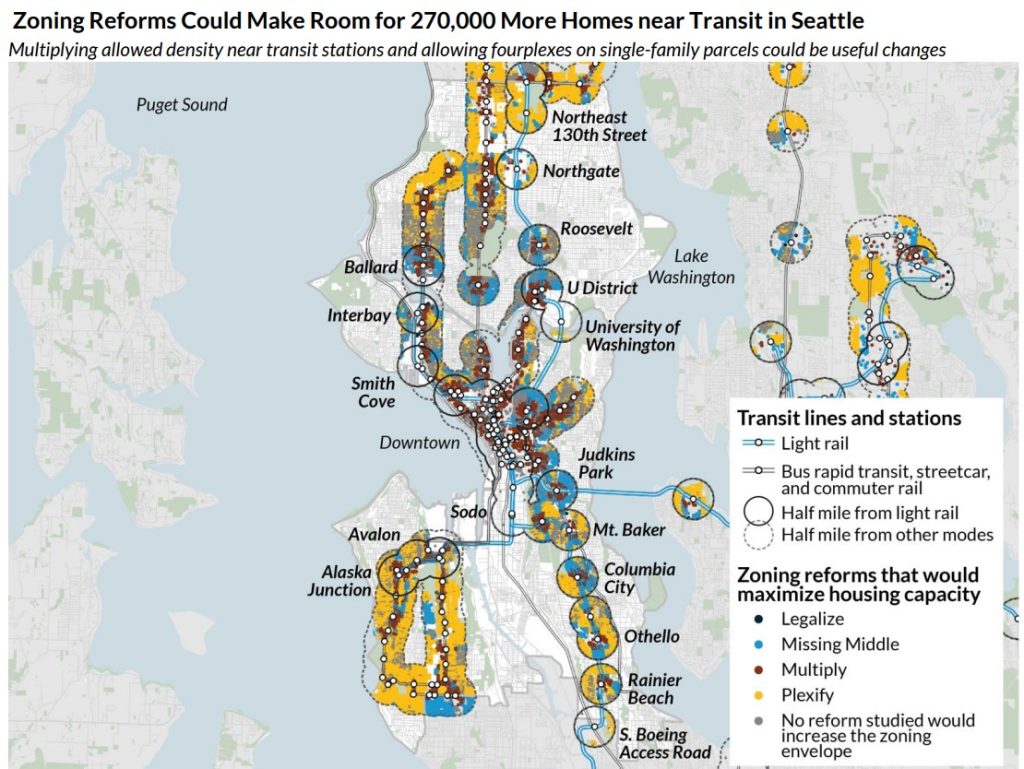

In Seattle proper, the reforms considered by Urban Institute would make room for 270,000 additional homes near transit, a 50% increase in zoning capacity. However, in cities the authors categorize as “high construction, high demand” the reforms would more than double zoning capacity, with “low-demand cities” and “low construction, high-demand cities” not far behind at just shy of a doubling in capacity.

The researchers state their goal was “to understand the effects of broad land-use policy change conducted through municipal, regional, or state-level action,” and they examined the following four potential reforms:

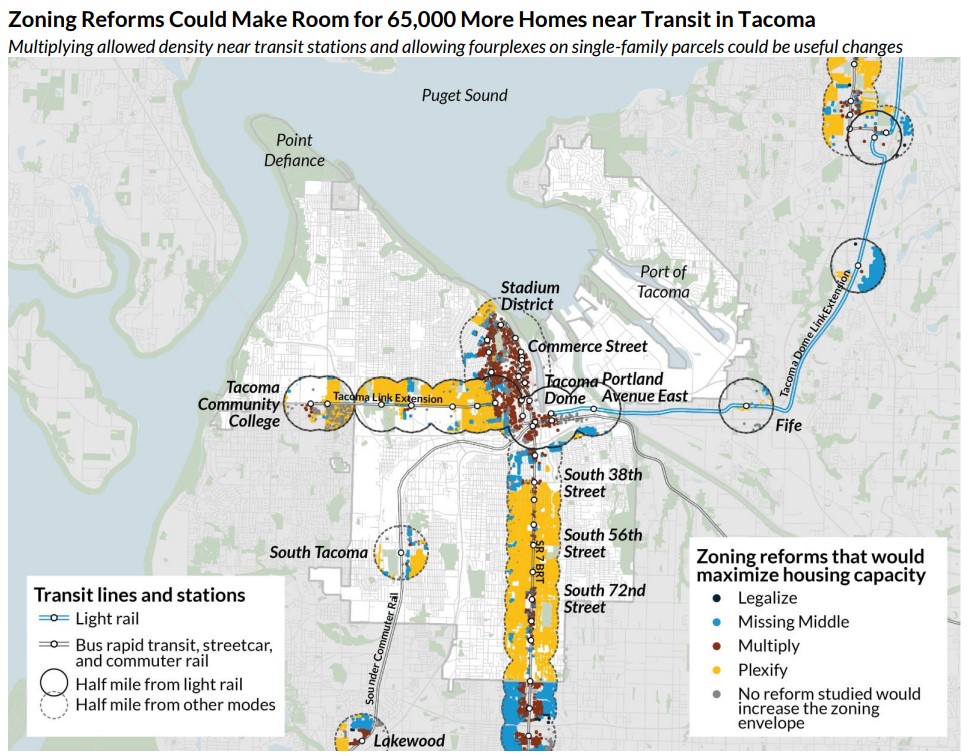

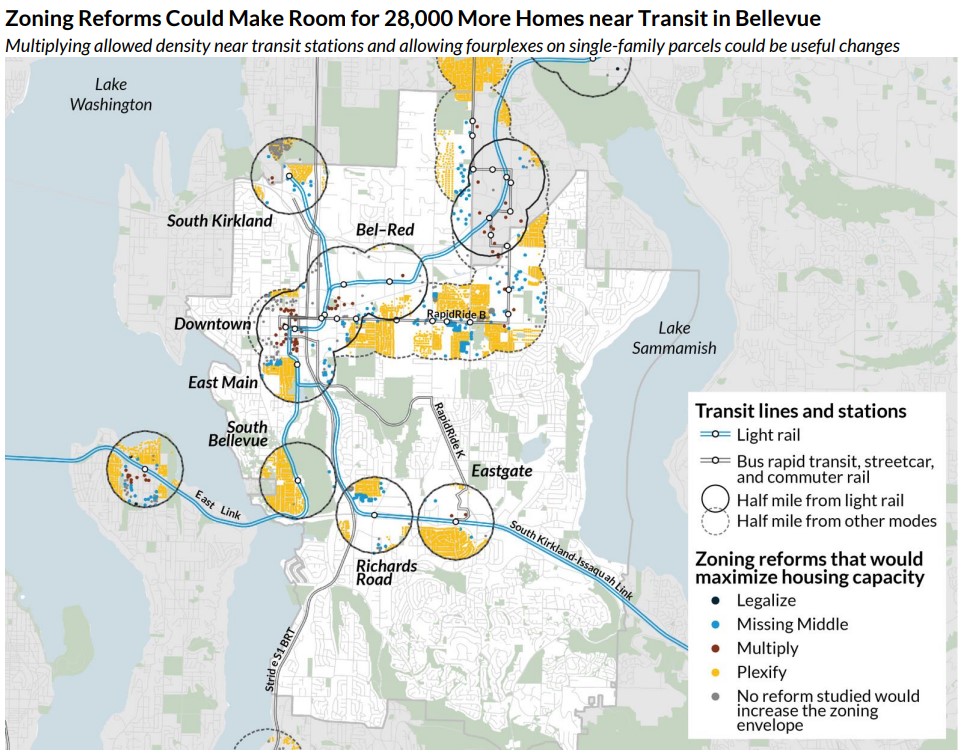

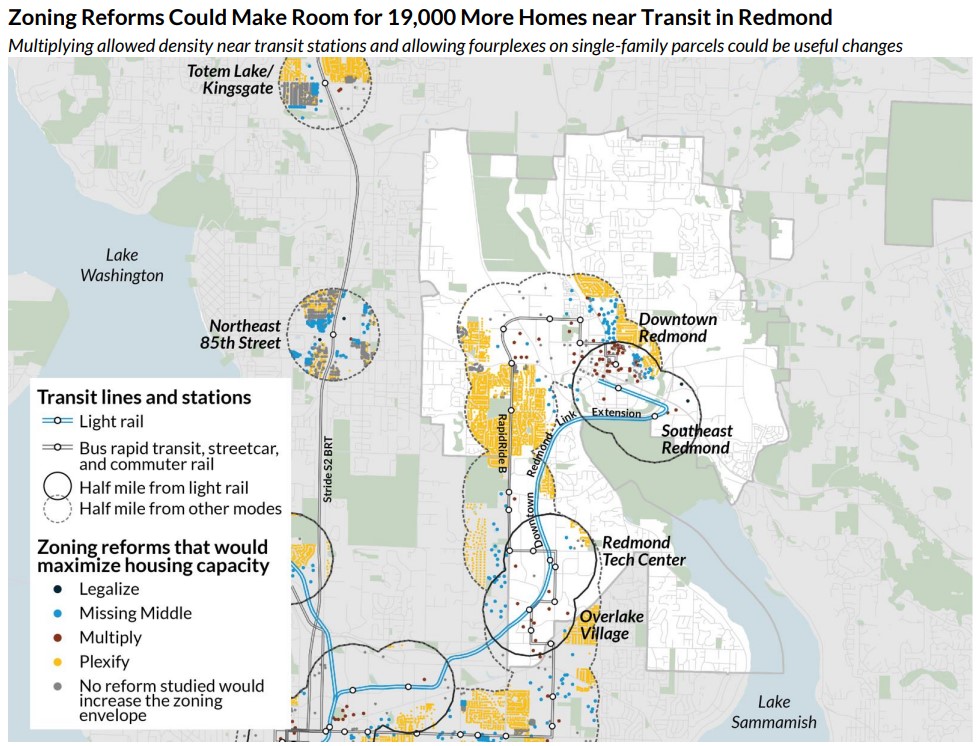

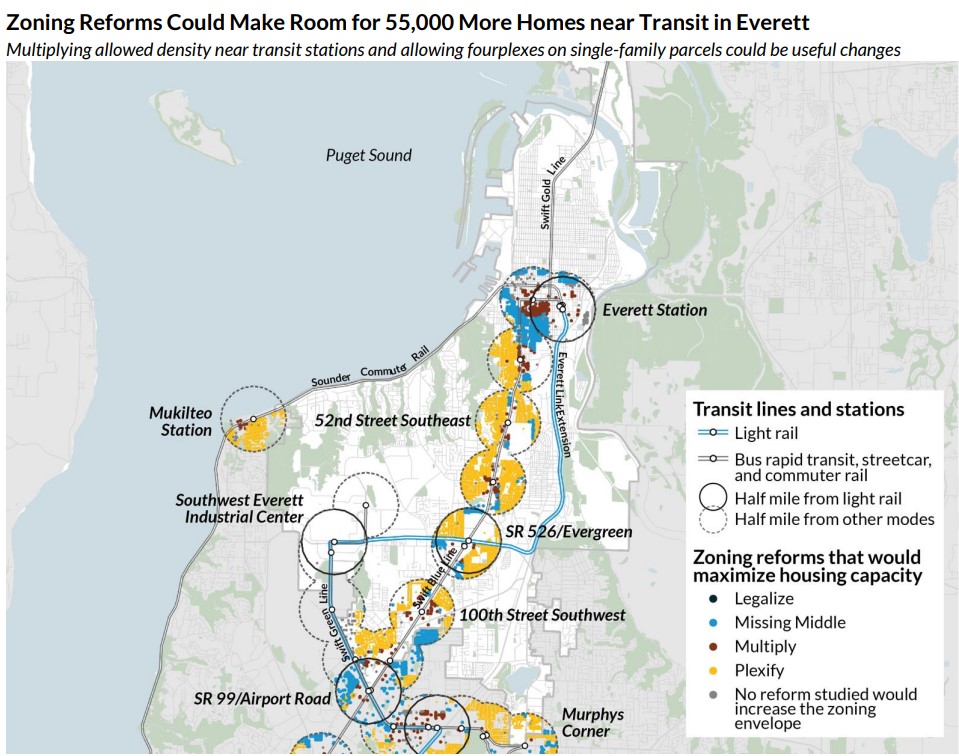

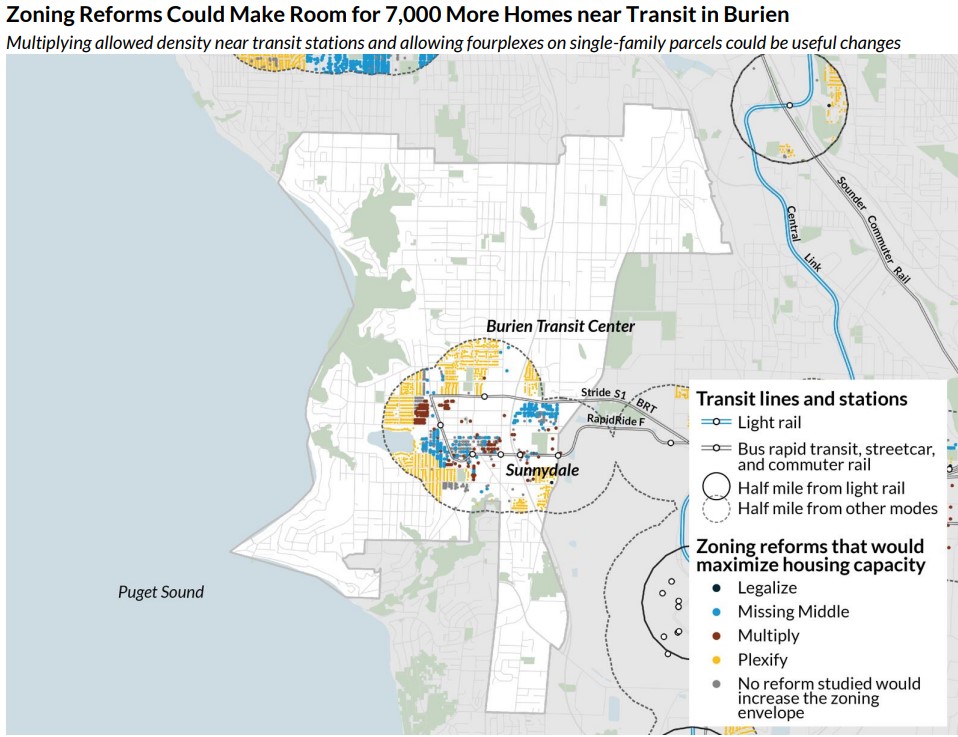

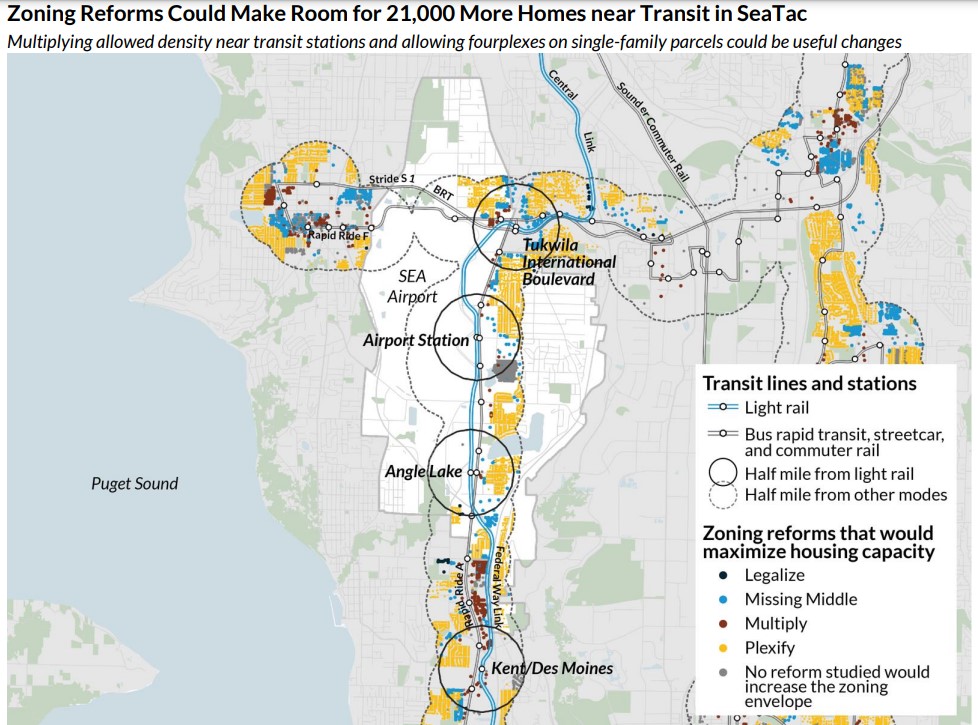

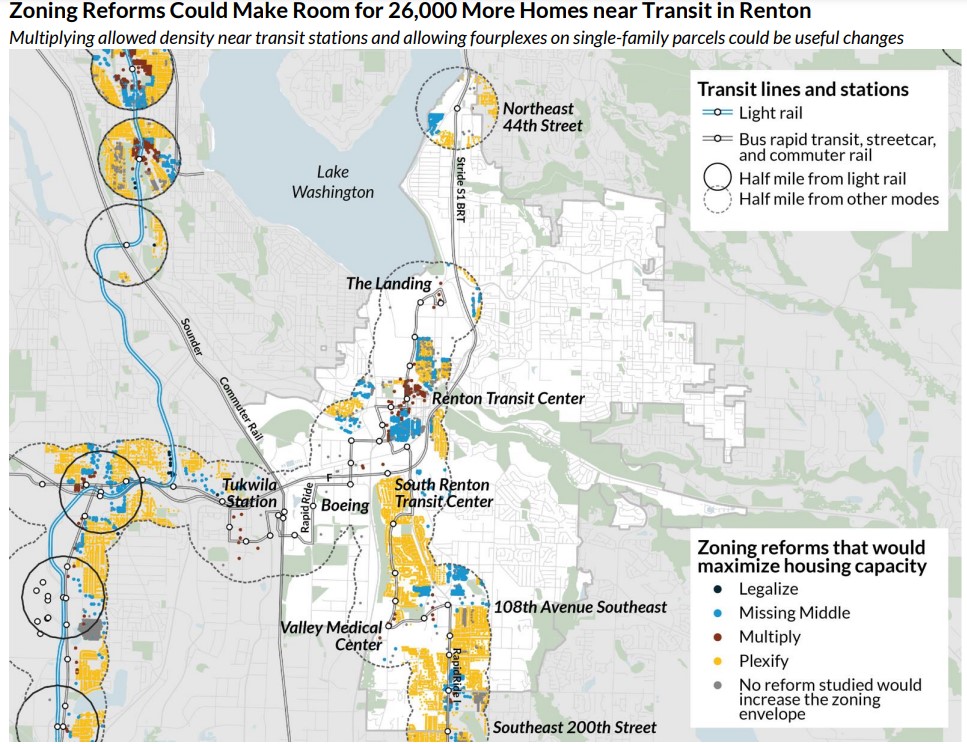

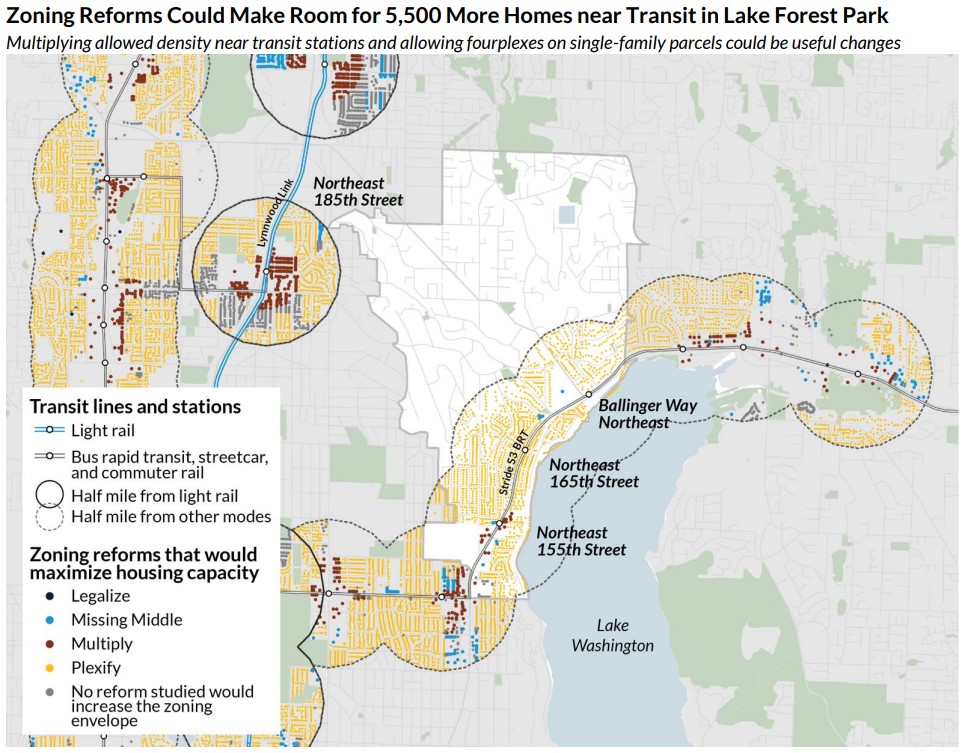

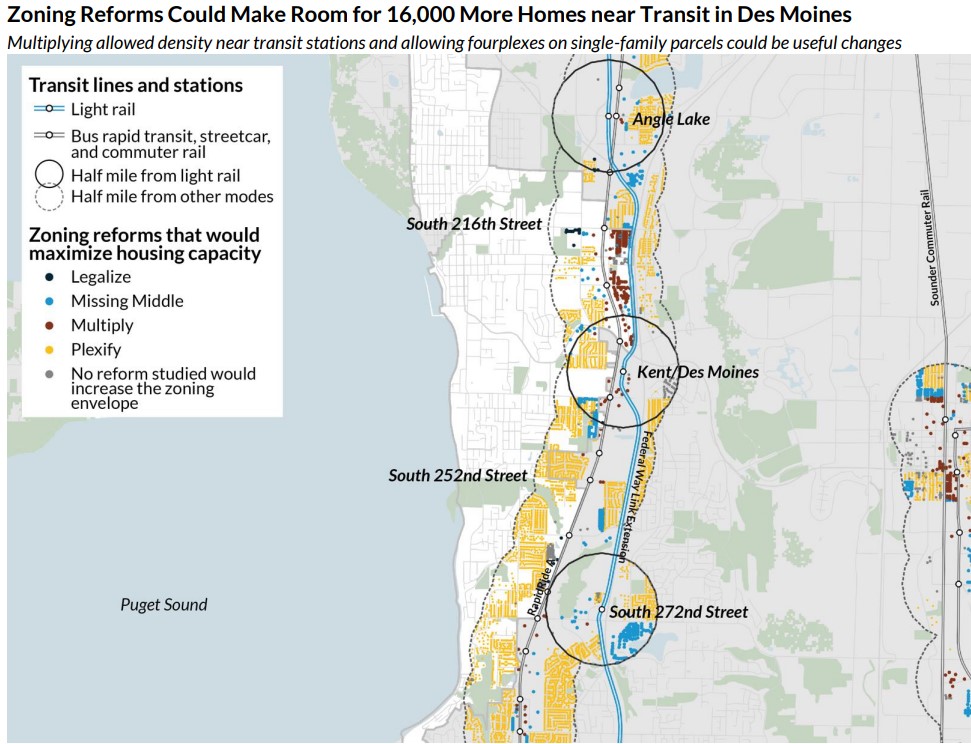

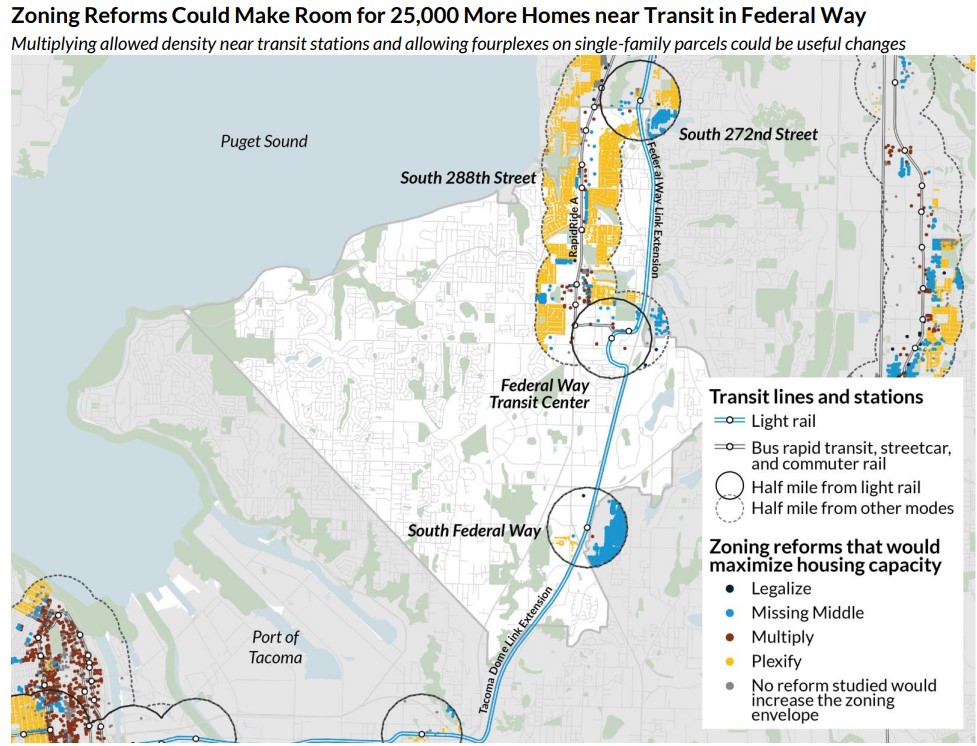

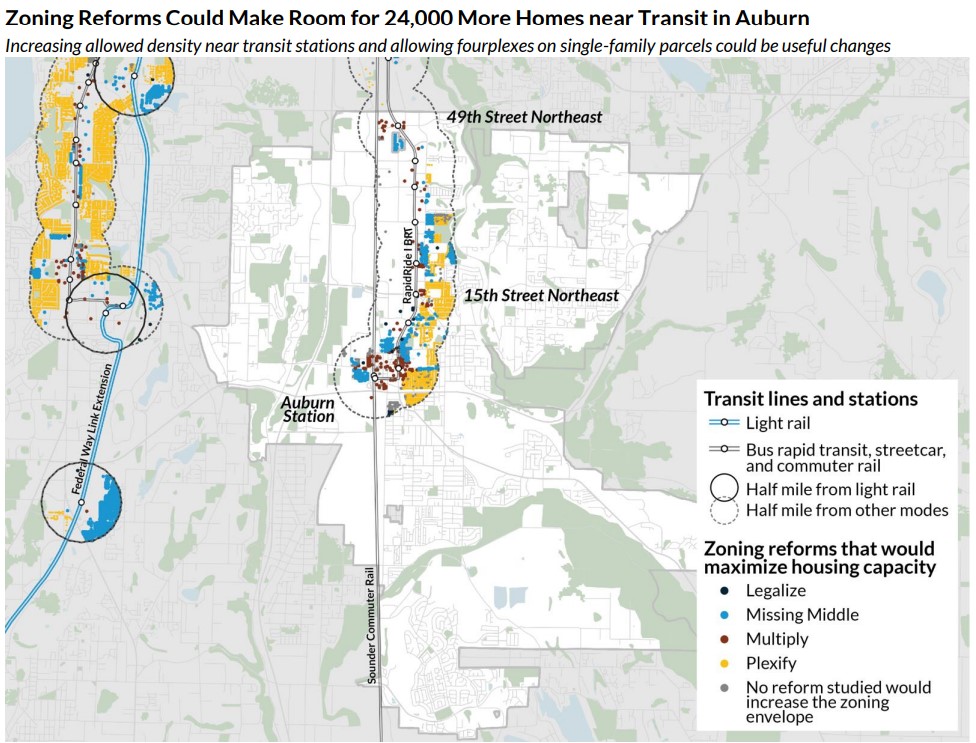

- “Plexify”: Allowing four-flat apartments in any residential zone that currently limits development to one-, two-, or three-unit buildings — shown in yellow on the maps.

- “Missing Middle”: Allowing up to 12 units in multifamily zones — shown in blue on the maps.

- “Multiply”: Allowing a 100% increase in developable housing units on lots within a quarter mile of stations — shown in red on the maps.

- “Legalize”: Allowing residential development on parcels that are currently zoned only for commercial, neighborhood retail, and public use — shown in black on the maps.

Once implemented, these changes could make a significant difference in a relatively short amount of time. “We project that if the government implemented all reforms together, the number of transit-adjacent housing units produced could increase by about 70% over the next decade, adding more than 60,000 units compared with the status quo,” the researchers wrote.

Freemark noted that their analysis of development trends indicated that the multiply option focused on dense multifamily housing near transit would result in the most new housing, but the “plexify” option was important for better distributing housing in high-demand single-family neighborhoods. For missing middle to really take off and scale up, developers and investors will need to figure out the model and work at a different scale than most operate now, as large apartment project of single-family development predominate.

“We believe that a broad-scale state rezoning policy could be an effective mechanism to encourage a fairer distribution of housing throughout the Puget Sound,” researchers wrote. “Requiring every community to demonstrate how it will provide the space for new units in the coming years — and actually ensuring that units get built in these locations — is a reasonable fair housing strategy and one that could counter the pernicious racial and class segregation that affects much of American society.”

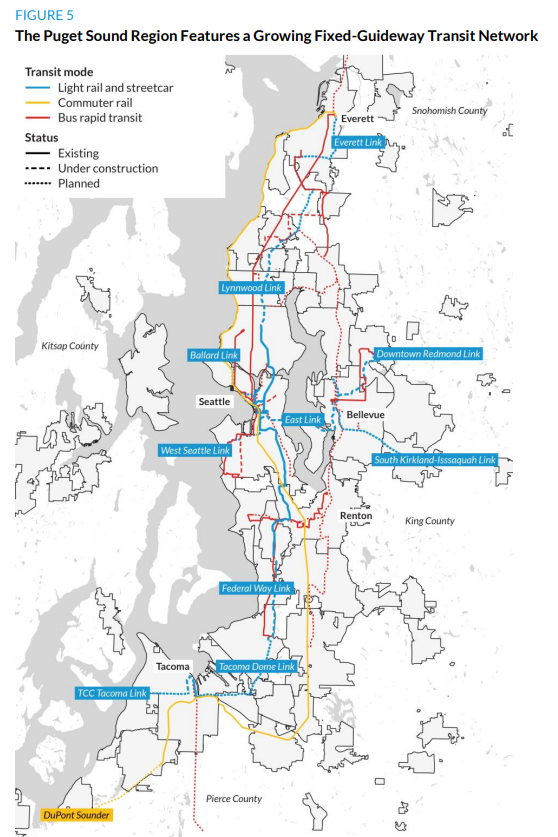

Zoning reforms would help the Seattle region get the most out of the major transit investments in the works. The region’s light rail network will stretch 116 miles plus 54 miles of bus rapid transit lines once the Sound Transit 3 package is completed over the next two decades.

“Major transit investments could transform regional mobility, but local rules currently limit housing growth,” they write. “Most housing is built in neighborhoods zoned for multifamily housing, but about one-third of station-adjacent land is zoned for only single-family homes. Almost 50 percent of this land requires at least one parking spot per unit, adding to housing costs.”

The package Urban Institute isn’t the same as the state bills and local reforms in the works, but it is similar. Rep. Jessica Bateman (D-Olympia) recently introduced a missing middle housing bill, HB 1110, that would legalize fourplexes in cities statewide, with the option for sixplexes if two units are set aside for lower income tenants. A bill focused on denser multifamily housing near transit is also planned, as we noted in our state legislative preview. We’ll continue to monitor those bills as they make their way through the process.

Research like Urban Institute just released only strengthens the case for broad zoning reform.

City-by-City Analysis of Zoning Reforms

Seattle

Urban Institute estimates Seattle would have room for 270,000 more homes near transit with the zoning reforms they modeled. They note that “plexify” option was particularly fruitful in West Seattle, where existing zoning is restrictive and largely single-family zoning.

Tacoma

65,000 more homes would be possible in Tacoma with Urban Institute’s reforms. The Tacoma Link streetcar extension and Pacific Avenue bus rapid transit would be the focal point corridors for changes. Tacoma already has zoning changes in motion with its Home in Tacoma rezone package.

Bellevue

The zoning reform package that Urban Institute proposed would add capacity for 28,000 more homes in Bellevue. With the RapidRide K Line in limbo with no firm timeline for completion, the researchers did not model “multiply” changes along the line.

Redmond

Redmond would have room for 19,000 more homes following the reforms Urban Institute studied. Light rail is due in Redmond by 2025.

Everett

The proposed zoning reform package in Everett would make room for 55,000 more homes. Zoning in downtown Everett is already pretty generous following a recent upzone, but other parts of the city continue to be largely zoned for low density residential development. The Evergreen Way and SR 99 corridor has rapid bus service and will have some Everett Link light rail stations eventually too.

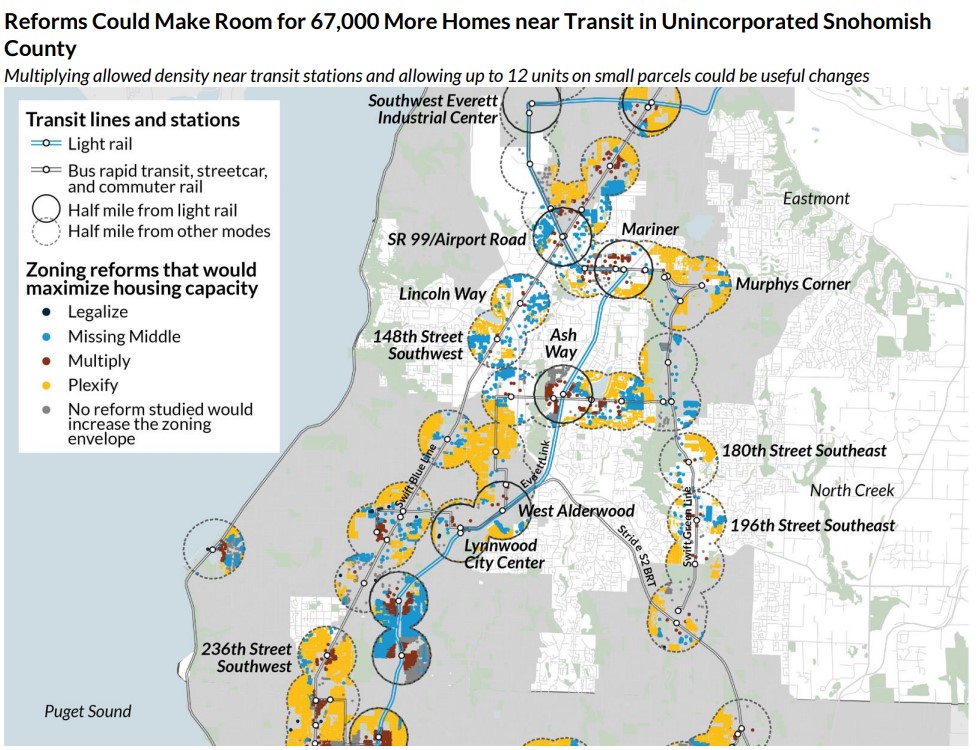

Unincorporated Snohomish County

67,000 additional homes could be accommodated in unincorporated Snohomish County with the reforms studied by Urban Institute. This area will get Everett Link light rail stations and Swift bus rapid transit stations.

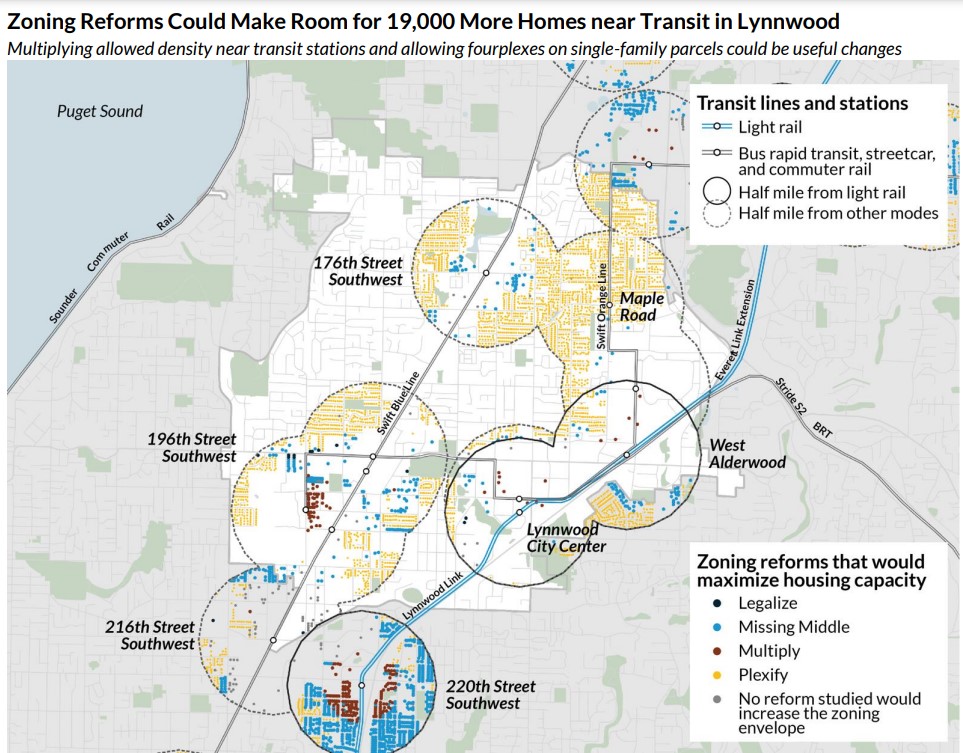

Lynnwood

Lynnwood would have room for 19,000 more homes primarily near its bus rapid transit stations and planned light rail stations, as Lynnwood Link arrives in 2024. Lynnwood has flirted with a housing backlash, but seems to have avoided it thus far.

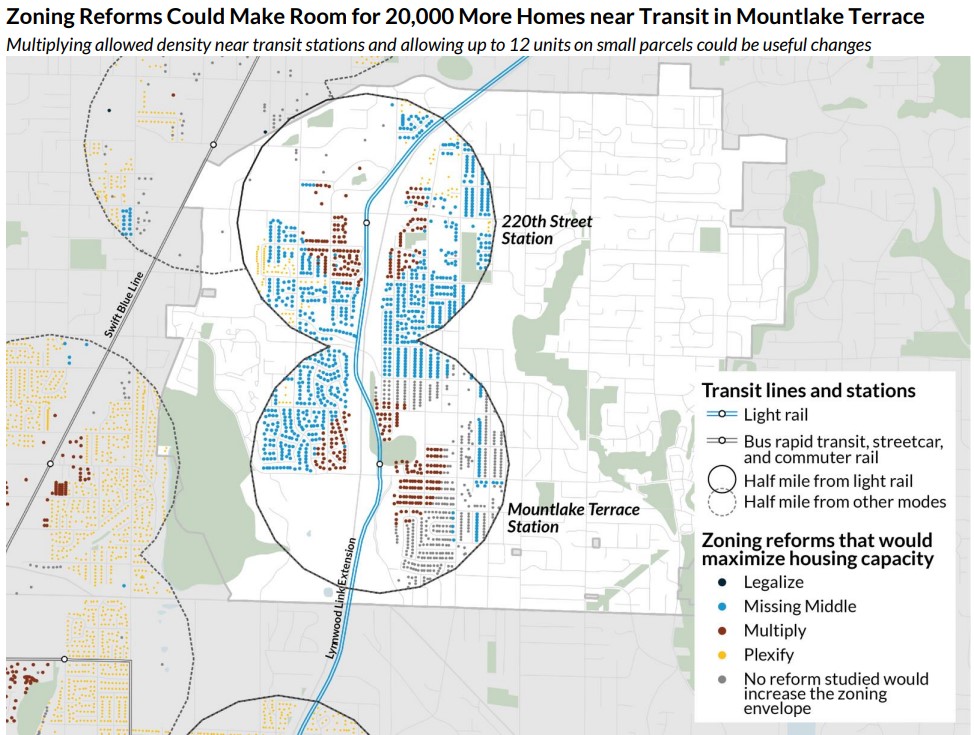

Mountlake Terrace

Mountlake Terrace authorized a rezone ahead of light rail arrival with the Lynnwood Link extension, but the changes are focused in a narrow area around its “downtown” station. Urban Institute’s package would make room for 20,000 more homes.

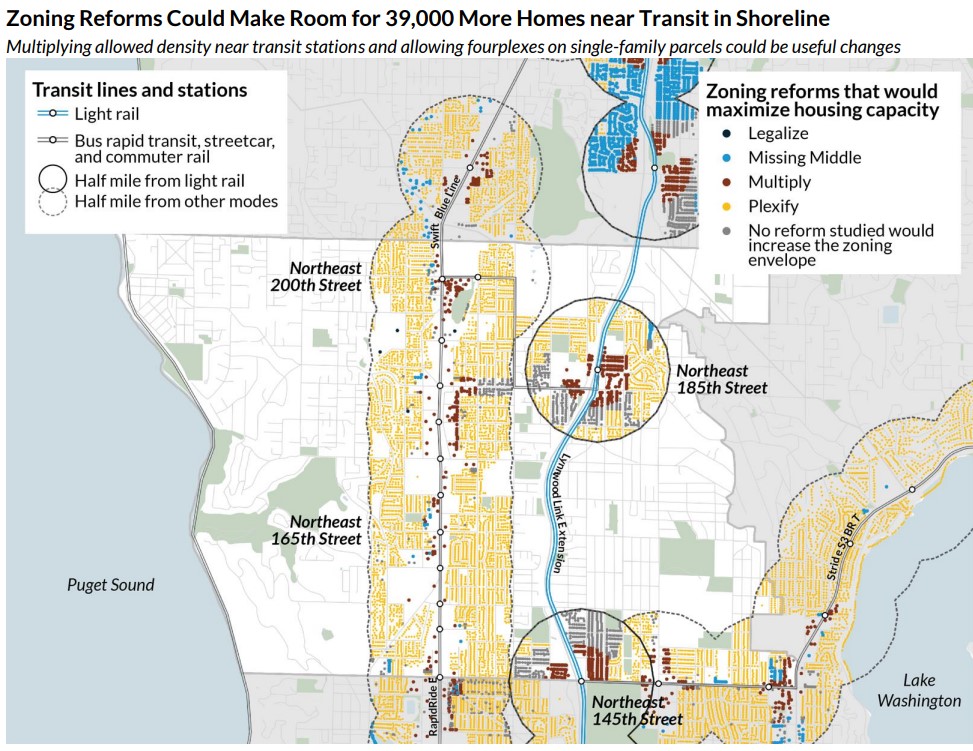

Shoreline

Shoreline has rezoned near its two soon-to-open light rail stations, but the Urban Institute package would go further, target the RapidRide E Line corridor, and also add zoning changes like fourplexes on single family parcels. Doing so would make room for 39,000 more homes.

Burien

Burien would make room for 7,000 more homes near transit with the reforms studied. Burien already has RapidRide F service and will add Stride S1 bus rapid transit service in 2026.

SeaTac

SeaTac could make room for 21,000 more homes near transit, which includes RapidRide F, Central Link, and, by 2026, Stride S1.

Renton

Renton would add room for 26,000 more homes under the studied changes. The RapidRide F Line serves Renton, and the I Line and Sound Transit’s Stride S1 will add more service in additional corridors.

Lake Forest Park

Lake Forest Park could make room for 5,500 more homes near transit, with its main corridor SR 522 along Lake Washington. The Stride S3 Line will upgrade service in 2027.

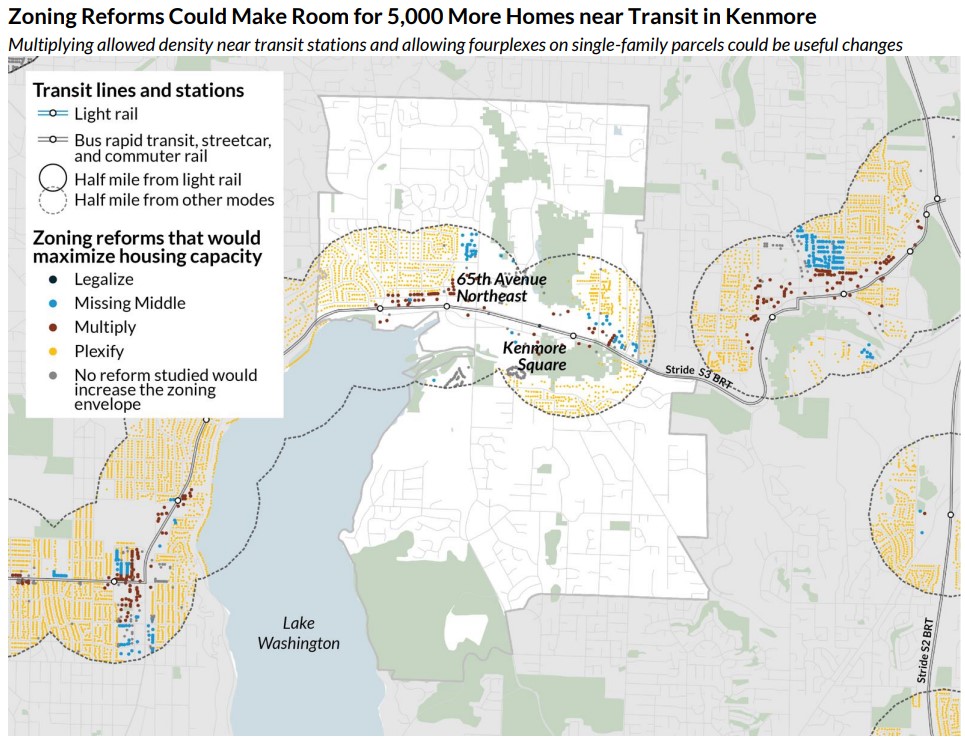

Kenmore

Kenmore could make room for 5,000 more homes via the studied reforms. Stride S3 will add bus rapid transit service in 2027.

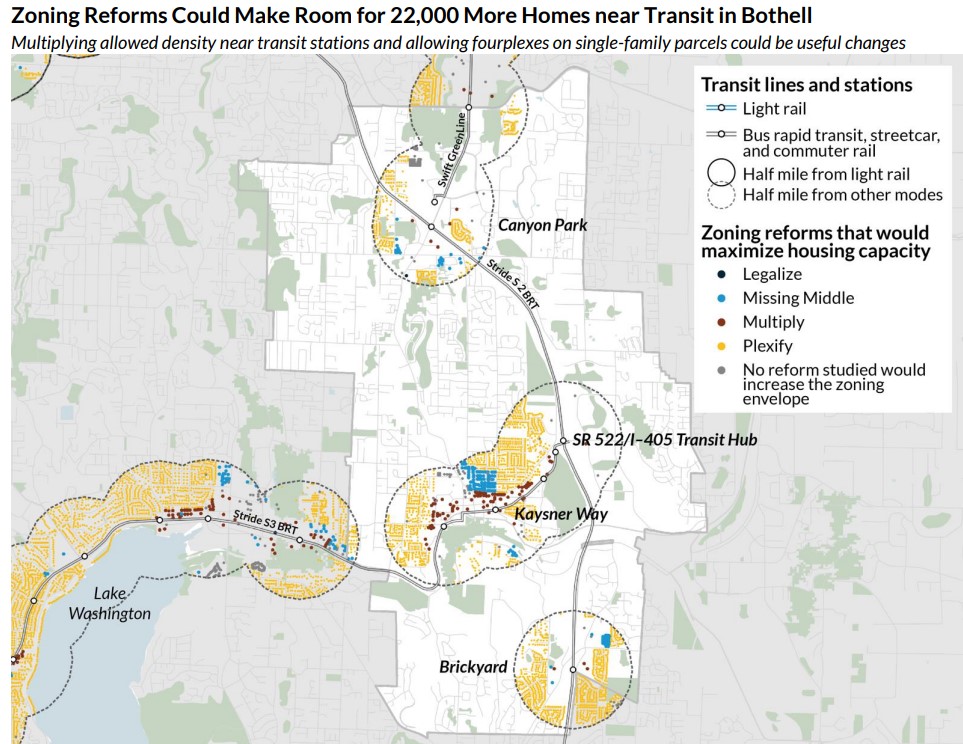

Bothell

Bothell could make room for 22,000 more homes near transit via the reforms studied. Bus rapid transit lines that serve or will serve Bothell include the Swift Green Line, Stride S3, and Stride S2.

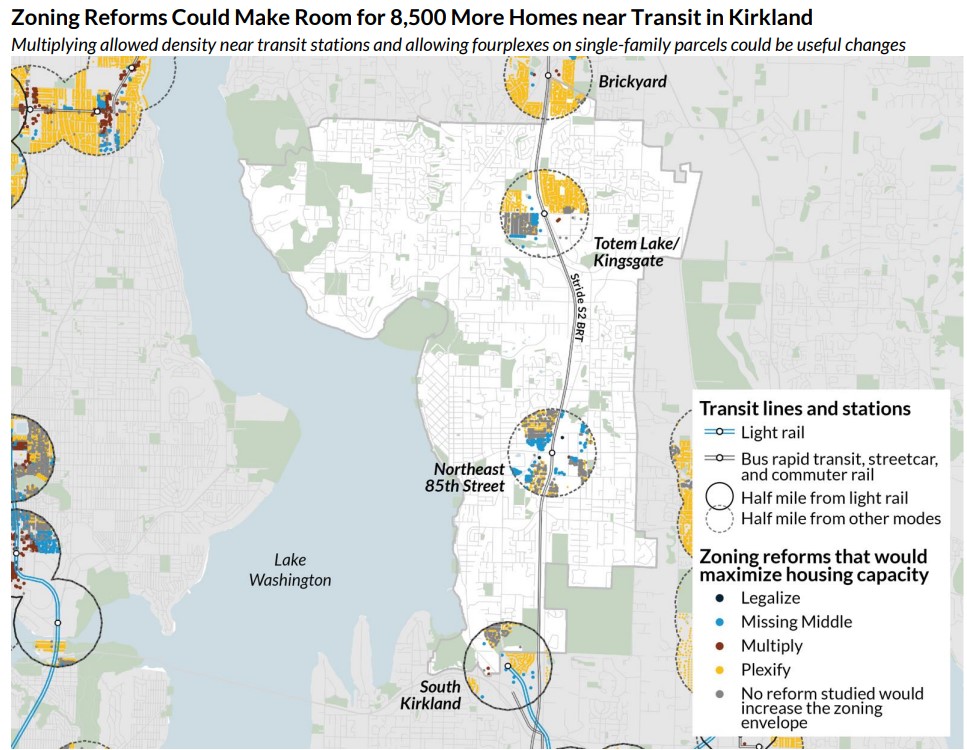

Kirkland

Kirkland could make room for 8,500 more homes near transit under the studied reforms. Adding more rapid transit in Kirkland could fill in the map and add to the total, such as via the delayed RapidRide K Line or extending light rail into the core of Kirkland.

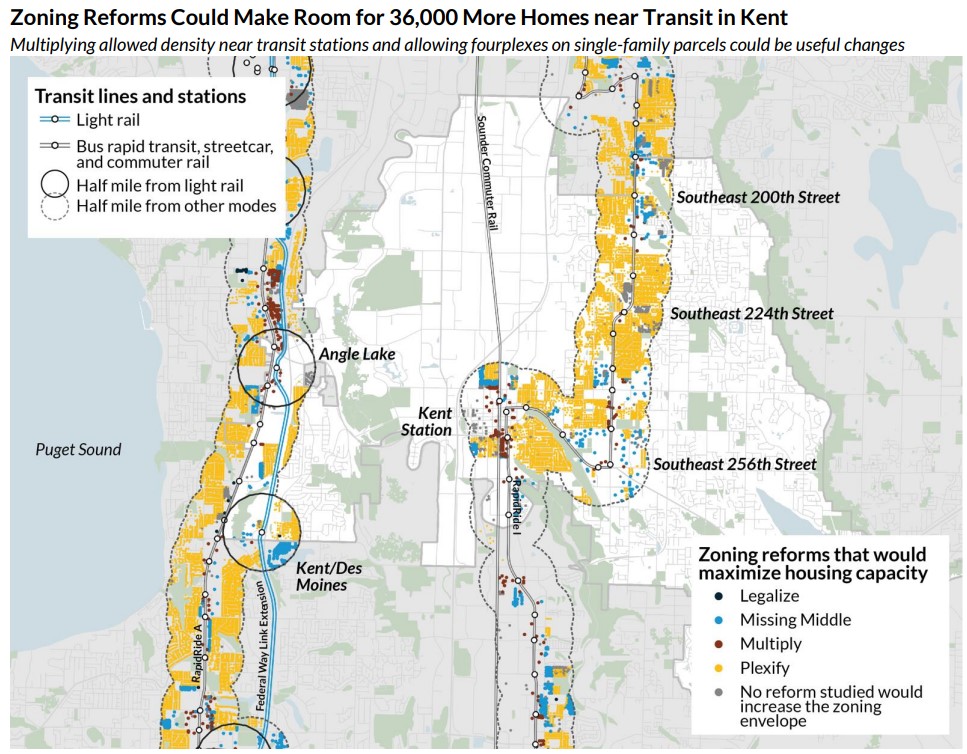

Kent

Multiplying allowed density near Kent’s transit stations will add room for 36,000 more homes. Kent has a South Sounder rail station, and Federal Way Link will serve the southwestern edge of the city. The RapidRide I Line will add service through the heart of the city.

Des Moines

Des Moines could make room for 16,000 more homes under the studied changes. The RapidRide A Line serves the SR 99 corridor, with light rail on the way via the Federal Way Link extension.

Federal Way

Federal Way has RapidRide A service and will have two light rail stations with the Federal Way Link extension and another with the Tacoma Dome Link extensions. The studied zoning reforms could make room for 25,000 more homes near transit.

Auburn

Auburn has a South Sounder station and the future RapidRide I Line will add further rapid transit service. Zoning reforms could make room for 24,000 more homes near transit.

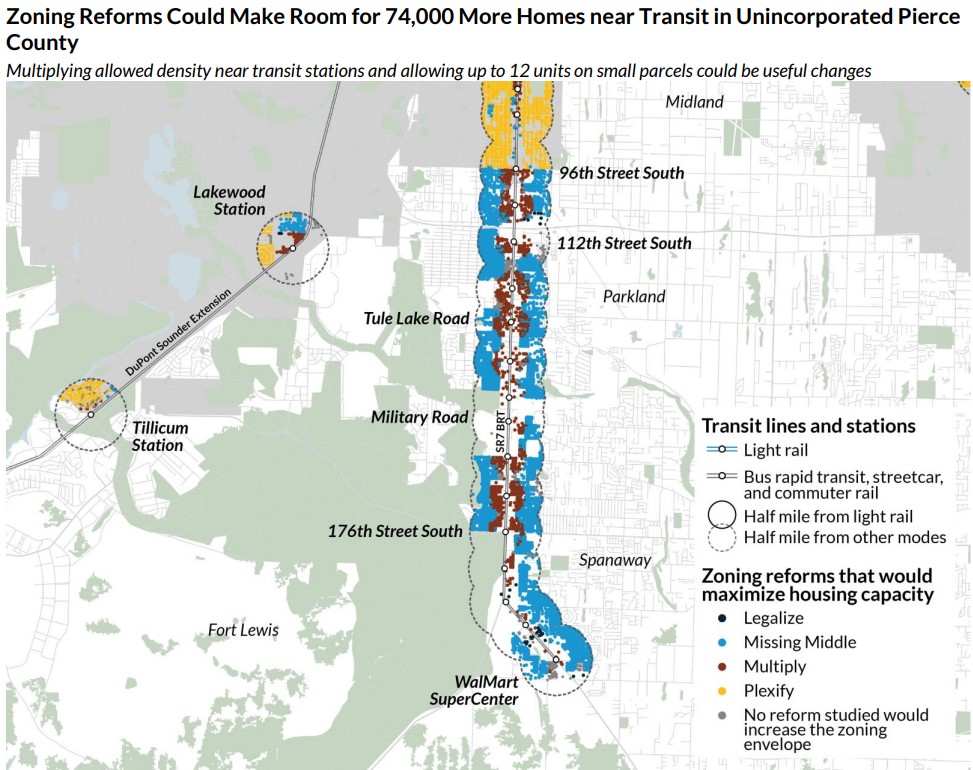

Unincorporated Pierce County

Much of suburban Pierce County is unincorporated and the planned bus rapid transit along SR 7 will serve much of this suburbia. The zoning reforms studied could make room for 74,000 more homes near transit.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.