It’s no secret that restrictive zoning is prevalent in the Seattle metropolitan area, but a new study underway at the Urban Institute is taking a comprehensive look at the extent and impact. Cities like Lake Forest Park, Newcastle, Normandy Park, and Mercer Island dedicate more than 90% of their residential land exclusively for single family homes, an early findings brief on Urban Institute study notes. The research team — Yonah Freemark, Olivia Fiol and Sophia Weng — is planning to release the full paper in January.

“More housing is essential, yet recent trends show that housing construction is inadequate to serve a growing population in the Puget Sound region,” said Freemark, the lead researcher in a statement. “The evidence is clear that local, state, and federal governments must develop new policies to guarantee housing availability.”

Freemark offered his assessment of the study’s findings when I reached him recently on the phone. We waded right into the debate about whether to only focus zoning changes narrowly near transit stations or apply them broadly across the vast swathes of land set aside exclusively for single-family homes. The broader option was proposed in Rep. Jessica Bateman’s statewide zoning reform bill, which had considered allowing sixplexes or fourplexes in many areas currently zoned only for single family homes.

“Our research for the Puget Sound suggests strongly that limiting the zoning change to just the areas directly around transit will do little to impact the inequitable distribution of housing availability and construction in the region today,” Freemark said. “So, if one of the primary goals of zoning reform or of housing growth is to encourage more access to housing including in areas that are quite exclusive today, just looking at the areas directly around transit — like the very close-in areas — I think is going to be pretty ineffective. We need a diversity of zoning changes implemented simultaneously.”

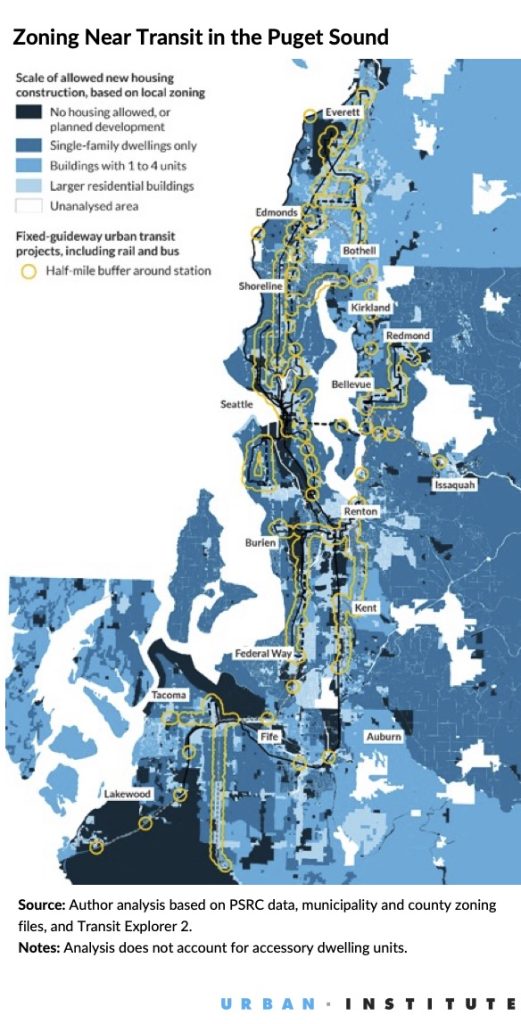

The researchers drilled down to study zoning and development patterns in 39 cities across the region using both local zoning ordinances and property-level data procured from an insurance company. A pattern emerged with some very restrictive cities that were almost entirely single-family zoning while other cities had a more mixed approach, with some transit-rich areas zoned for dense multifamily development, but other areas still blanketed in single-family zoning often despite having strong transit access.

Uneven growth not producing enough new housing

“More than 70% of all residential land in Bellevue and Seattle is now reserved for single-family homes,” the brief notes. “If the single-family zones allowed multifamily housing development, the region could add up to 65% more new housing permits — equivalent to 120,000 homes — depending on developer interest.”

Freemark said another category was areas that may allow housing growth, but are not getting it largely due to a lack of developer interest tied to lower wealth and housing prices in the area. He said chunks of South King County fell into this category, as does South Tacoma. Other areas have high demand and developer interest, but zoning restrictions and permitting barriers are holding back housing growth.

“In South Bellevue and in West Seattle there are just huge amounts of land near the existing and future transit system that continues to be quite restrictive,” Freemark added. “The lack of housing growth there is all about the land use regulations getting in the way.”

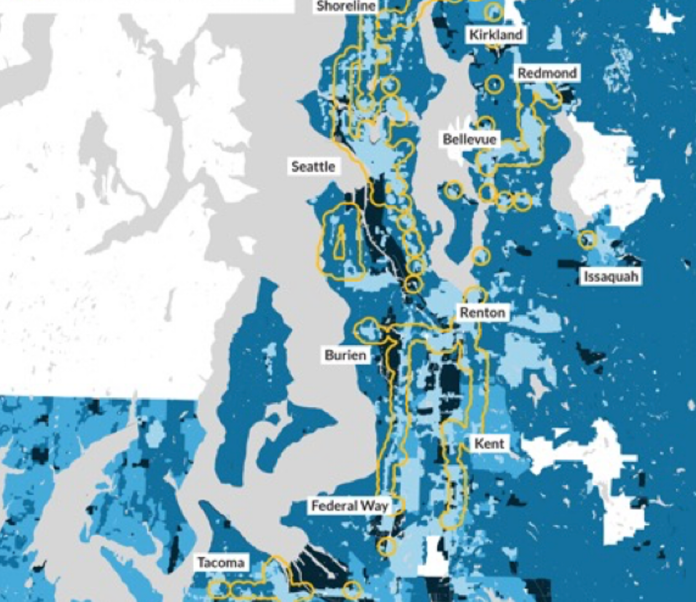

The zoning brief includes a map showing zoning across the Puget Sound Region overlaid with yellow circles showing the half-mile radius of frequent transit stations either open or in development. In 2016, the tri-county region approved the $54 billion Sound Transit 3 package that will eventually expand the Link light rail system to 116 miles and add more than 50 miles Stride bus rapid transit network. Despite the ambitious commitment to rapid transit, the commitment to housing growth has often lagged behind.

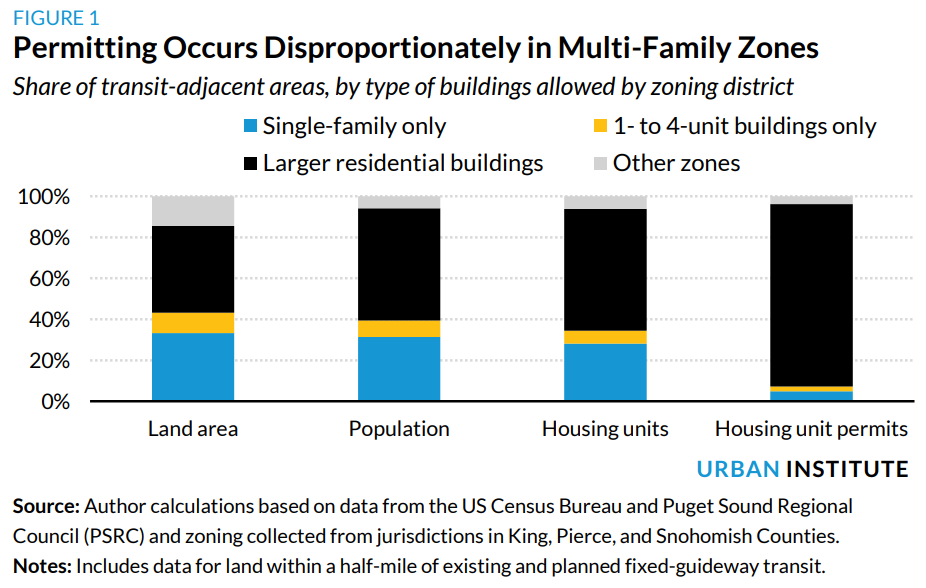

“Near transit, about a third of the land is restricted to single-family home construction. Yet less than 5% of housing permits are located in such zones—compared to almost 90% in zones that allow apartments,” the brief states.

The need for more housing couldn’t be any more clear in the Puget Sound Region.

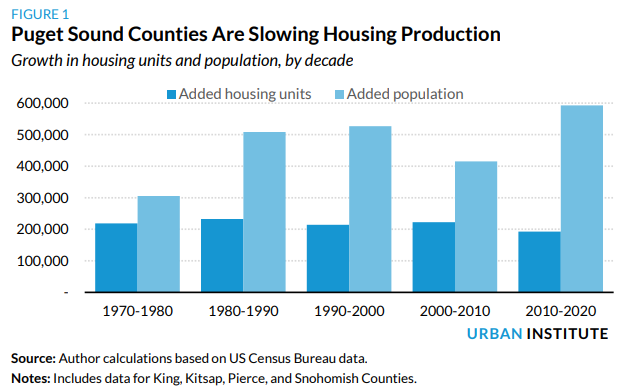

“The region had the largest increase in population per decade in the 2010s that it’s ever had, adding 600,000 people, but it had the smaller number of new housing units of any decade since at least the 1970s,” Freemark said. “Essentially we have a proportion problem where there’s this significant interested in moving to Seattle, but housing growth is not aligning with that. That is despite the fact that Seattle as a city and the region has overperformed the country as a whole. It just suggests even more work is needed to add enough housing to meet the need for growth for all the people coming in.”

“One of the things we show in our larger paper, which I wish I could show you right now, but I can preview it, which is to say different types of zoning changes have different sorts of effects depending on the station areas.”

Freemark argued rezoning broadly with a variety of zoning changes is best, with some larger upzones near stations geared toward maximizing housing production while replacing single family zoning with something like fourplex zoning having the aim of reducing inequity in land use and increasing access to exclusive neighborhoods with high opportunity.

“We’re able to conclude, for example, that large increases in density allowances near station areas are likely to produce the most new housing, but allowing for things like fourplexes on single-family land is going to do the most to encourage housing production in areas that are pretty exclusive right now — places like South Bellevue,” Freemark said.

The early findings brief on housing availability also includes a map that show how limited new housing construction has been across much of the region over the past two decades even as the metropolitan region has added about a million additional residents, growing from about 3 million to 4 million residents. Seattle is outperforming most of the close-in suburbs in housing growth as measured by new housing unit permits per 1,000 residents, a dynamic which appears to be pushing growth to outer suburbs — places like Fife, Arlington, Issaquah, and Bonney Lake.

Lessons from Chicago

Freemark previously authored a study of a Chicago upzone focused around transit that affected 6% of the city’s land and found that land value quickly adjusted in the upward direction, but new housing growth was slower to respond. This finding was seized on by upzone skeptics to argue against zoning changes in their own cities and claim it would be counterproductive. The study became important enough to the housing debate in San Francisco, for example, that Freemark penned an op-ed in The Frisc in which he debunked claims by upzone opponents, who he said “distorted” his study. He preached caution in taking the study out of context, especially when applying it to wildly different contexts. A broad upzone of low density single family land is going to have a very different impact than that concentrating on already dense multifamily land near transit stations, for example.

“The impacts of changes in zoning rules is location-dependent, context-dependent, and can have positive and potentially concerning outcomes. No question,” Freemark said. “Limiting zoning to single family homes is inherently making it hard to add new housing units. One thing worth pointing out about my Chicago work is that it was not about upzoning single family homes.”

“Keeping housing limited to single family homes inevitably reduces housing availability and this increases housing costs,” Freemark added. “There’s no other possible way to have a future of housing in that context. If you limit all housing construction to single family homes, by definition you’re limiting the amount of construction occurring, and we show that in this data with Seattle. There’s no housing construction being done in single-family areas, and if the Seattle region needs more housing, it has to identify the way to allow more of that housing to come in.”

To put a finer point on it, Freemark emphasized a do-nothing (or very little) approach is not the answer.

“My contention is that we have to be careful and methodical about the way that we undertake zoning reform, but not doing a zoning reform is also not the answer,” Freemark concluded.

Looking ahead

With Seattle and other jurisdictions in the region in the midst of once-a-decade “major update” to their Comprehensive Plans, getting these zoning questions right will be key to navigating out of the housing crisis. With the updates due by the end of 2024, the clock is ticking to land on the strongest land use plan, which Urban Institute’s research indicates should include a diversity of zoning increases applied broadly and methodically to maximize the impact on housing availability and equity.

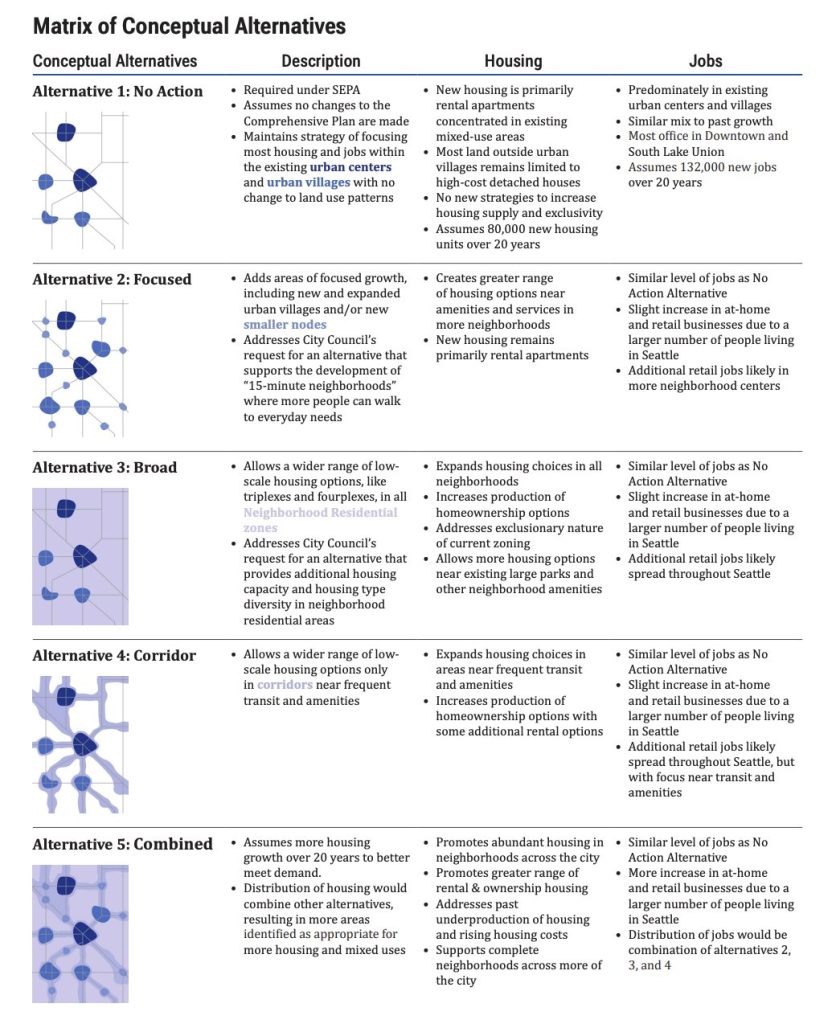

In Seattle’s context that gives the “combined” Alternative 5 the edge of concepts contemplated thus far — unless the Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) adds a bolder Alternative 6 as housing advocates (including The Urbanist) have urged. Missing middle housing (like fourplexes or sixplexes) in single-family zones and even greater multifamily density allowances within a 15-minute walk of frequent transit could be quite the one-two punch, as this new research suggests. But such an approach will require mayors and city councils around the region to follow the data, and demands state legislators to lend them a hand in reforming restrictive local exclusionary zoning.

Correction: An earlier version of the article noted Kirkland as one of the cities with mostly single-family zoning. While Kirkland had veen mentioned in the report as a predominately single-family zoned city, Kirkland’s zoning code was changed in 2007 to allow duplex and triples in most single-family zoned areas (per Chapter 113.20 of the zoning code). The code has since been updated a few times to ease some of the restrictions on this allowance. Houghton, the one exception, is expected to have its exemption removed, as its community council with land use authority has been abolished by a freshly passed state law. While it currently may be difficult to build these multifamily buildings in Kirkland due to some quirks in the zoning code (such as high parking requirements), it is not technically correct to say to Kirkland is mostly zoned for single-family homes. Urban Institute has since revised the brief and updated the map. An earlier version also stated 95% instead of 90% zoned single family for the most restrictive cities, which has since been corrected.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.