Fifteen housing advocates applied for 15 open seats on Seattle’s design review boards this winter. A public records request revealed that all 15 were shut out as the City opted instead to appoint mostly architects with connections to major firms or past or current board members, even in seats set aside for non-architects. For housing advocates, that rejection underscored how at odds the review program is with their goals.

“Design review is a continuation of practices like exclusionary zoning and redlining that are used to keep out unwanted neighbors and separate communities,” Laura Loe of Share The Cities said in an email. “We aren’t getting a more beautiful city, it isn’t more climate friendly, and it isn’t more affordable. We have a choice here to take care of a laundry list of reforms for design review or maybe we just don’t need it at all.”

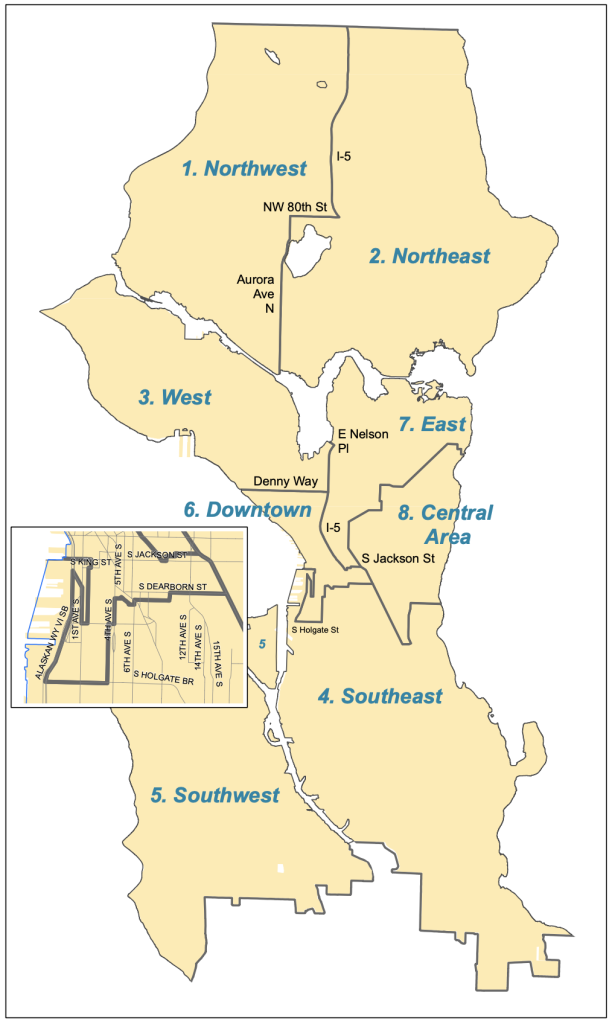

The City’s eight design review boards are composed entirely of volunteers, but they wield great power in the housing approval process. For multifamily projects that meet design review thresholds, a recommendation from the local design review board is an essential step in getting a Master Use Permit (MUP), which is itself a necessary hurdle to get a building permit. The threshold to trigger full design review in most cases is exceeding 35,000 gross square feet of development, which hits nearly every large apartment project.

Design review meetings take place on weekday evenings and can run three hours or longer, which makes it hard for working-class parents or service workers to participate, especially since the work isn’t compensated (outside of being a resume-builder for architects). Relatedly, design review membership is overwhelmingly White, with just four members of color participating before the latest round of recruitment. Five boards currently remain all-White even after the new batch of recruits. The Central Area design review board is the only one with Black members.

The boards can call a project back to as many design review meetings as it wants if they’re unsatisfied with elements of the project. Theoretically, the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) can override a design review board and issue a MUP without a board recommendation, but that rarely happens in practice.

In December, The Urbanist put out a call for urbanist applicants in hopes of reinvigorating the board with new perspectives and perhaps moving them in more pro-housing direction. With all the applicants from this call rejected, it leaves housing advocates instead look for structural reforms to avoid predatory delays and boost housing production. Making design review less of a hurdle could involve raising the thresholds so fewer projects go through design review and capping the number of design review meetings. Other ideas include streamlining design review guidelines and packet requirements so less paperwork is required.

A tool of predatory delay

Developer Maria Barrientos of the firm Barrientos Ryan agreed it’s high time to reform design review.

“There are projects that I believe are just fine that work well that end up going to three, four, and five design review board meetings that doesn’t, in my head, really make a difference in the experience for people who are going to live there,” Barrientos said. “All it does is add time and money. That to me is a little mindboggling — I gotta say. I don’t understand it. That’s where the comment that design review is being misused as a tool to stop or slow development rather than encouraging good design — and good design is so subjective.”

Her firm is all too familiar with the pitfalls of the design review system. Their high profile Queen Anne Safeway project has been tied up in the design approval process since the Bush administration, albeit with a big chunk of that under a previous design and developer. While the Queen Anne project now has its design review recommendation, Barrientos reports that the building permit still isn’t forthcoming due to lengthy correction rounds and a slow-to-respond City planner tasked to them.

Barrientos has found that boards can be swayed to delay a project, but rarely weigh positive feedback as seriously. “If the neighborhood is negative, that influences the board, but if they’re positive in support of a project that seems irrelevant to the board,” she said.

She also pointed to the rigid requirements of the design review program that start adding delays and costs early in the process. For example, in the Early Design Guidance (EDG) phase, developers must present three massings (renderings that show different shapes the proposed building could take) in their design packet, even if they already have landed on a clear favorite.

“Part of EDG feels like a superfluous use of time. Honestly, all developers run scenarios on numerous configurations of a building. And you end up with one that works the best. Sometimes, there’s two that work really well and you’re ambivalent. But you come in with a preferred plan, and it’s not like the design review board ever says no you can’t do that one, because that’s the one that makes the most sense,” Barrientos said. “So just to be able to say this works for us and work that through with a planner would be way faster. The amount of paperwork and presentation documents to go to EDG is so out of scale in proportion with what you’re getting feedback on. It’d be great if you just had one design meeting.”

Supporters of design review have argued the costs of the increasingly laborious and lengthy program are worth it due to higher quality buildings, but Barrientos disagrees. She estimated the cost of design review to the developer is $600,000 to $800,000 plus eight to 12 months of delay, which also adds indirect costs by requiring builders to hold land for longer periods before breaking ground. The incentive for developers to produce high quality housing comes not from design review, she argued, but from competition for tenants. She contested with the idea that design review forces developers to invest more in the quality of the building.

“We’re all jockeying for people to rent our buildings,” Barrientos said. “So, the more you can spend to make the units better and the amenities that the residents use, you’re going to be able to lease and keep your residents. Your retention rates are better. The concept that developers could care less about things like that is absurd, because in the end, operationally net operating income is very important. Having occupancy and residents staying and not turning over is a huge part of that, but people don’t ever connect that dot.”

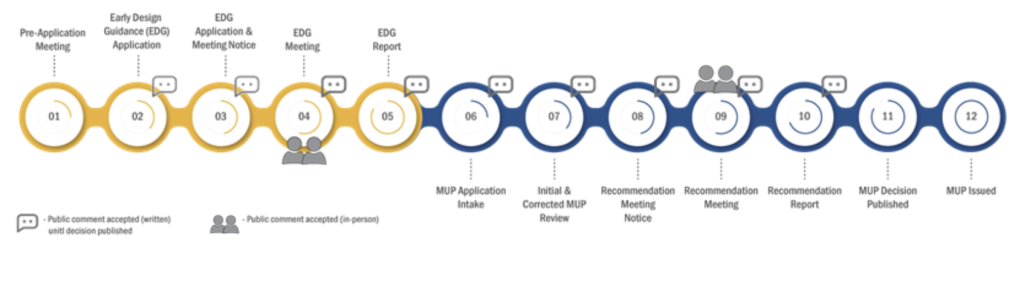

A recent ECONorthwest analysis of the design review program counted 12 steps to get a MUP, which still leaves the builder with more work and hoops to jump through to get the building permit allowing them to start construction. The building permit phase is when SDCI verifies the project meets fire code, earthquake code, plumbing codes, and will not collapse. Thus, it’s not the design review MUP phase that guarantees those necessary safety elements. Other cities like Tacoma have organized their whole approval program around the building permit and foregone a separate MUP altogether, which helps explain why their design approvals are reportedly three times faster.

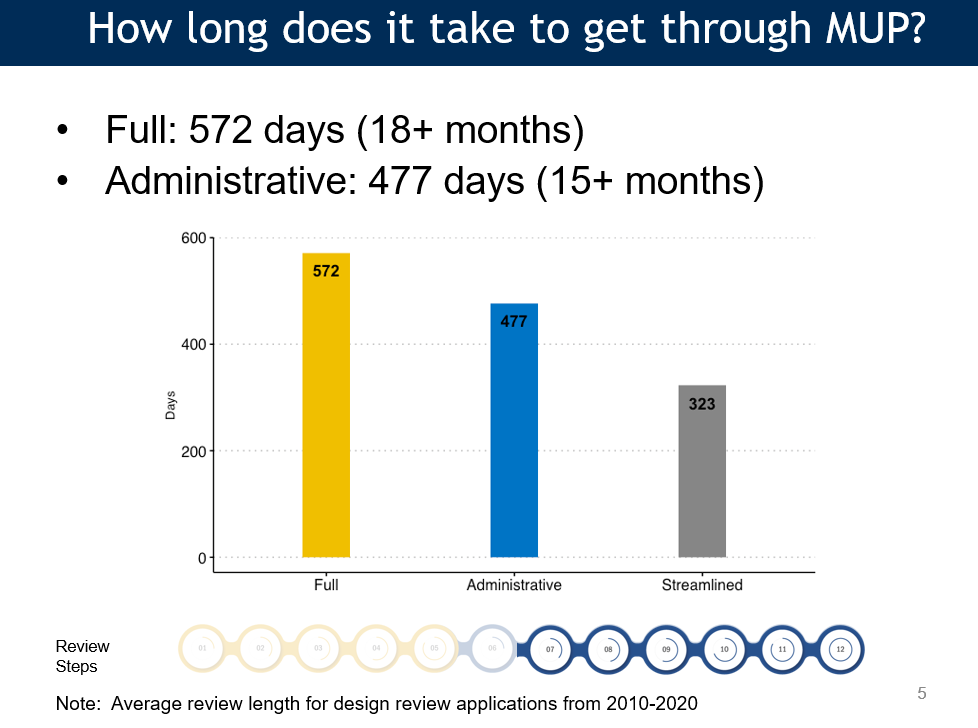

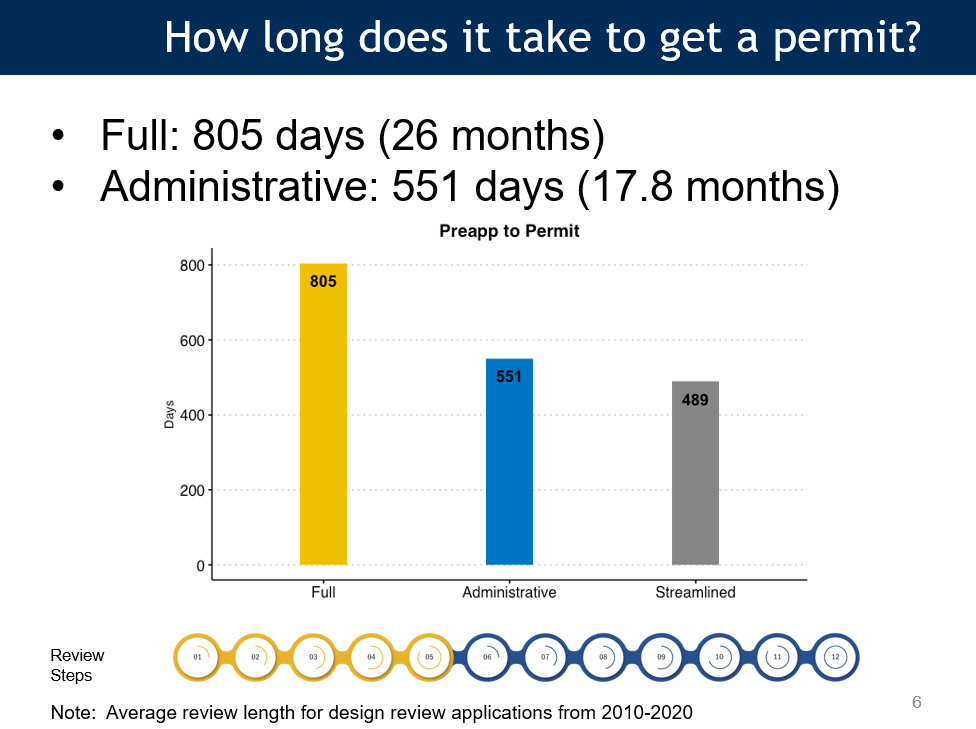

ECONorthwest found that design review is taking more and more time to complete. From 2010 to 2020, the average time to get a MUP exceeded 18 months for full design review. A developer still has to get a building permit after getting the MUP, so this doesn’t encompass the entire permitting time.

It also doesn’t count pre-application work, which is only getting more onerous. One change made along with the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, was adding a community outreach requirement before a project can enter Early Design Guidance. Adding another step has made the “pre-application” phase even more time-consuming. ECONorthwest found that counting pre-application extends the average full design review time to 26 months over the past decade. Notably, the extra time was less dramatic for administrative design review, where pre-application added 2.5 months instead of an extra eight months. This suggests putting more projects through administrative design review instead of full design review would shave several months off total permitting time.

An ombudsman to clear red tape?

Barrientos stopped short of saying the design review boards should be disbanded or fully circumvented, but she did highlight a path to smooth out the process.

“The biggest thing we’d want is an ombudsman assigned to help you when you have comments and responses that border on personal design opinion that don’t make the project, the design better and certainly don’t make the lives of the residents better,” Barrientos said. “It tends to end up being ‘this is my design preference’ and there’s no connection, in my mind, to the citywide goals of creating more housing quickly to make sure there’s enough housing for everyone, and then this laborious process we go through that delays the production of housing by eight to 12 months. It’s a huge disconnect… It’s like the citywide goals and what design review board does are totally on different planets and independent. To me, that is a very important thing that needs to change.”

An ombudsman could also provide help for builders whose projects are stymied by overly picky or slow City land use planners. Review time varies widely from planner to planner, even on similar projects, Barrientos said, and some are more apt to inject their own personal design preferences in what is supposed to be a neutral process of applying the written design codes and guidelines.

What Barrientos said mostly squares with what I’ve heard from other developers — including Ben Maritz, who noted Tacoma permits housing projects three times faster than Seattle. And the delays hit both market-rate builders and nonprofit affordable housing builders alike. An extra design review meeting to fuss over the color palette delayed Community Roots (then Capitol Hill Housing) affordable housing project next to Capitol Hill Station by months, which they noted added significant costs.

“Just like any developer, we suffer the costs of project delays in the form of things like interest on pre-development loans, added design costs, and increases in construction costs (via materials and labor),” Ashwin Warrior, Community Roots’ then-communications director, said at the time.

Promoting architectural diversity and creativity

In addition to heaping costs on builders and slowing housing creation, Barrientos argued our current iteration of design review promotes an architectural sameness and discourages projects geared toward moderate-income residents.

“Design review sometimes pushes you to monochromatic projects that are way too similar and the emphasis that you must have certain massing and design and exterior materials and cladding and that they all have to be high quality. High quality materials cost money and it will affect rents. I don’t know that it necessarily makes for a better neighborhood architecturally, because architectural diversity to me is the foundation of what makes a neighborhood interesting.”

Architectural tastes change with the times, and design review’s limiting of architectural variety could end up disappointing future generations rather than living up to our presumption of presenting them with a gift, particularly if those future generations do not share the same architectural preferences design reviewers assume they will. Welcoming a greater variety of designs would guard against this outcome. Or as Loe put it: “The idea that we can come to community consensus about aesthetics and not end up with a boring city visually doesn’t make sense to me.”

The Urbanist‘s own syndicated columnist and Passive House architect Mike Eliason pointed out the design review advice and guidelines also are incompatible with environmentally sustainable Passive House standards, which generally favor simple “dumb boxes” over tapered buildings with a variety of materials and modulating facades that are hard to insulate. Nonetheless, the latter is what design review boards tend to promote. If the City is serious about shrinking the carbon footprint of its building sector, the present design review program and guidelines stand squarely in the way.

Is design review reformable?

Attempts to reform the design review program from the inside have shown little promise. Switching to virtual design review at the onset of the pandemic presented an opportunity to tweak the program and work out some kinks. However, more projects going through administrative design review hasn’t been a panacea, with developers noting that some SDCI planners can be slow to respond or throw up similar obstacles as design review boards did.

Simply putting more pro-housing voices on the design review boards hasn’t borne fruit either, as noted in the introduction. This was made more surprising by the fact the City extended the deadline for that recruitment, saying there was a dearth of applicants. A public records request shows that 15 of 53 applicants referenced The Urbanist or another similar pro-housing referrer such as Matt Hutchins (himself a former design review board member) on their design review board application and all 15 were summarily rejected. The 15 rejected urbanist-minded applicants were intriguing candidates that included artists, software developers, and even case workers for immigrant refugees — in addition to the architects and development professionals that the program overwhelmingly favors for seats.

Meanwhile, applicants with connections to people or architectural firms already on the design review board tended to breeze through and find themselves appointed to boards. Of the selections made, nine were direct past or present board referrals, and four others worked at firms where past or current board members are employed. All nine referrals were accepted by this program, highlighting the preference by the City to pick architects by insider selection. It’s increasingly seeming like an insular club overwhelmingly composed of well-connected architects rather a program that truly reflects the diversity of Seattle. The City appears to be doing nothing to counteract this trend.

The design review program may have started out with the best intentions. However, over the course of years, it has morphed into a tool of delay and exclusion, becoming an obstacle to buildings seeking to meet the highest standard of environmental sustainability. If Seattle is going to chart a course out of its dual crises of housing affordability and climate change, something has to give.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrianizing streets, blanketing the city in bus lanes, and unleashing a mass timber building spree to end the affordable housing shortage and avert our coming climate catastrophe. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in East Fremont and loves to explore the city on his bike.