“The City, both the Council and Mayor, are not seeing the opportunity that we have in the midst of a crisis,” Mayoral candidate Bruce Harrell said in a recent phone interview. “The inaction that I’m seeing…”

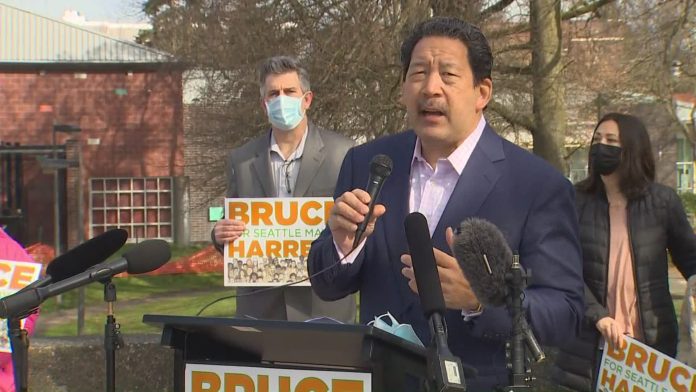

While Harrell has been crystal clear that he will seek to take action, the contours of his policy program are fuzzy, particularly when it comes to public safety, police reform, affordable housing, zoning, and homelessness policy. This hardly makes him unique in a field that is heavy on candidates, but relatively light on specific policy programs. Nonetheless, for a promise of swift action to ring true, the vision also must be clear. Harrell announced for Seattle Mayor on March 16th and did offer a few more specifics in our interview earlier this month, but also relied heavily on a catchphrase of his — “I will follow the data” — that doesn’t tell us much.

What happens when two metrics point us in opposite directions? How do we know which one to follow? And who are these data miners? In times like these, policymakers fall back on their overarching vision, strategy, and their inner circle of advisors, and their track records in office can betray a pattern. Harrell does have 12 years on City Council and five days as temporary mayor in 2017. But much like his interview, Harrell was a cautious councilmember that largely avoided rocking the boat. For some that may offer hope of a steady hand, while others are hoping for a more daring captain ready to forge ahead boldly.

Culture change not Defund

Harrell has been critical of the movement to defund the Seattle Police Department (SPD) and argued he is ideally situated to lead on culture change at SPD. To that end, Harrell has suggested that Seattle police officer training should include viewing the nine-minute video of George Floyd being strangled to death by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. While he clarified that watching the video would be optional, he thought which officers declined to watch could be illuminating and perhaps identify problematic recruits.

“While many of us, particularly in the African American community, were alarmed and angry as well, but this was not a new revelation for us. Many of us have lived this,” Harrell said. “If you’ve seen picture of me from the 70s with my afro and big leather coat, you’d have to assume that on occasion I’d have a less than pleasant experience with police officers, particularly going to Garfield [High School] in the 70s.”

“What I didn’t see was the city thinking about the end game after we marched, after we gave speeches, after we had debates. That there was a void of an end game, and what I mean by that is what reform should look like, whether it was abolishing the police or reforming the police,” Harrell said. “What I saw, quite candidly, was the city dropping the ball.”

Harrell pointed to both the issue of police roughing up peaceful protesters and to the mistake of cutting the salary of Police Chief Carmen Best (who presided over that roughing up and tear gassing). That paycut and some forced officer layoffs (which haven’t happened in Seattle in generations) caused Best to resign, but she landed on her feet with TV commentary gigs on KING 5 and MSNBC. The City Council ended up passing a 17% cut to SPD’s budget in the fall of 2020 after Mayor Durkan vetoed their earlier efforts at reining in SPD’s spending and brutal crowd control tactics.

“I don’t have the data to know what the percentages of an increase or decrease should be,” Harrell said. “But I will say generally, if you are trying to make a department world class, masters of de-escalation, effective, and efficient, you don’t starve them of resources. You make sure your investments are the right ones. So, we will open up the data.”

Harrell pointed to his Race and Data Initiative as a vehicle for this data-heavy analysis.

“There’s very smart developers and data miners that can look at the budget and can actually assist the City in looking at where efficiencies can be had and where realignment of resources can be made,” Harrell said. “So, under my process, we’re going to open up as much data as we can.”

Exploring land use changes

Harrell’s record as a Councilmember on land use and zoning was mixed, and he declined to make any firm commitments to pursue zoning changes in his term, whether via the major update to the Comprehensive Plan due in 2024 or otherwise. Asked about the rezone plan near 130th Street Station, Harrell did offer a blanket statement in favor of exploring land use changes near light rail.

“I think every station, just about, where we have room for smart growth around the light rail station should be explored,” Harrell said. “Again that gives us a great chance to have transit-oriented development and have walkable and livable communities.”

As a Councilmember, Harrell supporting increasing parking at light rail stations, voted against zoning changes near Roosevelt Station (as Nathalie Graham noted), and opposed an upzone at the Lowe’s site a few blocks north of Mount Baker Station as Erica C. Barnett covered back in 2014. The Lowe’s site has sparked some recent controversy since Amazon is seeking to build a distribution center there in place of 15-story apartment buildings that are otherwise permitted there. On the other hand, he did vote for Mandatory Housing Affordability rezone package in 2019 — though his district amendments did err on the side of lessening zoning capacity.

Transportation vision

Harrell touted that he was only candidate to have released a transportation plan so far, though his remains pretty high level. “Continue investing in safe sidewalks and bike lanes while implementing Vision Zero concepts that will help keep every commuter safe,” reads one bulletpoint. It’s unclear if the vision is a ramping up of investment and progress or a holding surf with our current pace, which under Mayor Durkan has been tepid.

Would Harrell seek a larger transportation levy to replace the expiring 2015 Move Seattle Levy that invested $930 million over nine years? This is where his signature “follow the data” phrasing surfaced again in place of a specific answer.

A look at his plan suggests a bigger levy would be necessary. Harrell’s transportation vision makes expensive pledges to “accelerate the repair and maintenance of aging facilities like the West Seattle Bridge, Magnolia Bridge, and other critical infrastructure,” expedite Sound Transit 3 (ST3) light rail timelines, and expand electric vehicle charging infrastructure. “Increase e-bike usage and support electric cars by placing and constructing charging stations so they are widely available and conveniently located,” his plan states. “As demand for gasoline decreases, work to clean up and repurpose valuable land for electric vehicles, affordable housing, retail, and community uses.” The Magnolia Bridge replacement alone was pegged at $266 million in 2019, with the 1:1 replacement option a heftier $420 million.

Arguably, funding for street safety projects could be secured through another of Harrell’s proposals: a program to give each of the seven district-based councilmembers $10 million per year to invest in their district, money he says can be found in the existing budget, rather than by raising new revenue. Thus budgets would be getting squeezed elsewhere, possibly from elsewhere in the transportation budget given Harrell’s opposition to reducing SPD’s budget and an easily skimmed $70 million being pretty hard to find lying around elsewhere.

The program’s focus areas are listed as small business recovery, homelessness solutions, parks and open space, cleanliness, pedestrian and public safety strategies, or cultural facility preservation. So, the money could end up getting spent in a wide variety of ways.

For those Seattleites whose councilmembers have largely opposed street safety projects (and as a District 4 resident represented by Alex Pedersen, I count myself among them), giving the local district councilmembers control over a big pot of money from the existing budget is pretty worrying since it adds another hurdle to getting street safety projects funded.

Climate and breaking car dependence

Harrell touted his climate credentials which included his vote for the Seattle Green New Deal and his work to build support the road diet in his district, which converted Rainier Avenue from four lanes to three in Columbia City. He said opposition to new safety projects, such as the Durkan-canceled 35th Avenue NE project, could be overcome if the City communicates the vision better and describes a narrative that explains to residents why bike lanes and other street safety projects are needed.

“When we look at future generations, as stewards of the planet, we also have to build for the future,” Harrell said. “I’m hopeful that people realize that cars will become smaller; we will be less dependent on cars. There will be more electrified modes of transportation, and bike lanes for example are one component of this ecosystem.”

But hearing from community is important, Harrell said, and he would follow the data on where exactly bike lanes and safety projects are appropriate.

Homelessness policy

Harrell disputed the criticism that his philanthropic push to fund supportive housing and homelessness services amounted to a GoFundMe proposal as one of his opponents, Andrew Grant Houston, quipped. On one hand, GoFundMe-style crowdsourcing can be very effective, he argued, pointing to the story of Two Brick Rick from Garfield High School, whose funeral expenses were paid by a successful GoFundMe campaign that also raised enough money to establish a scholarship in his name. Harrell said he wants to aggressively “tap into” the wealth of the region and mobilize corporate workforces to aid in the charitable work.

On the other hand, Harrell was open to new revenue sources to pay for supportive housing and homelessness services, he said, and saw his dynamic nonprofit partnership plan as supplemental rather than a replacement for additional government investment.

Harrell has backed Compassion Seattle’s Charter Amendment that would require the city to produce 2,000 units of emergency and permanent supportive housing in the next two years, after which point the City would be obligated to “keep City parks, playgrounds, sports fields, public spaces and sidewalks and streets remain open and clear of encampments.”

“I don’t use the term sweeps for two reasons,” Harrell said. “Number one: it connotates a degradation of the person that you’re trying to deal with, in this case an unsheltered person. Number two: it means different things to different people. I’d lead with Housing First. I’m opposed to arbitrary and random sweeps moving a person, a homeless person, from one place to another.”

While Bruce Harrell may not like the term “sweeps,” his support of Compassion Seattle (backed as it is by proponents of sweeps) suggests he’s not opposed to the concept when push comes to shove. Like Hansel following a trail of breadcrumbs, the data could lead him anywhere.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.