When Neal Lampi, longtime Real Change vendor and former staff member, was living in his vehicle, moving among spots ranging from industrial areas of SoDo to a stretch of road adjacent to Green Lake, it was for one reason: He couldn’t afford rent.

Lampi was working at the time — “A lot of people living in vehicles are working,” Lampi said — although circumstances that came to the fore during the pandemic stopped him in his tracks, he said. But he also had nearly $65,000 in higher education debt, and an apartment in the city in which he had lived for more than 20 years was out of reach.

Some refer to vehicle residents as “the forgotten homeless”: people who fall through the gaping cracks in services and programs meant to help people experiencing homelessness. Some have too many resources to qualify for government assistance; others consider the tradeoff between their greatest asset — their vehicle — and less attractive shelter options to be a poor one.

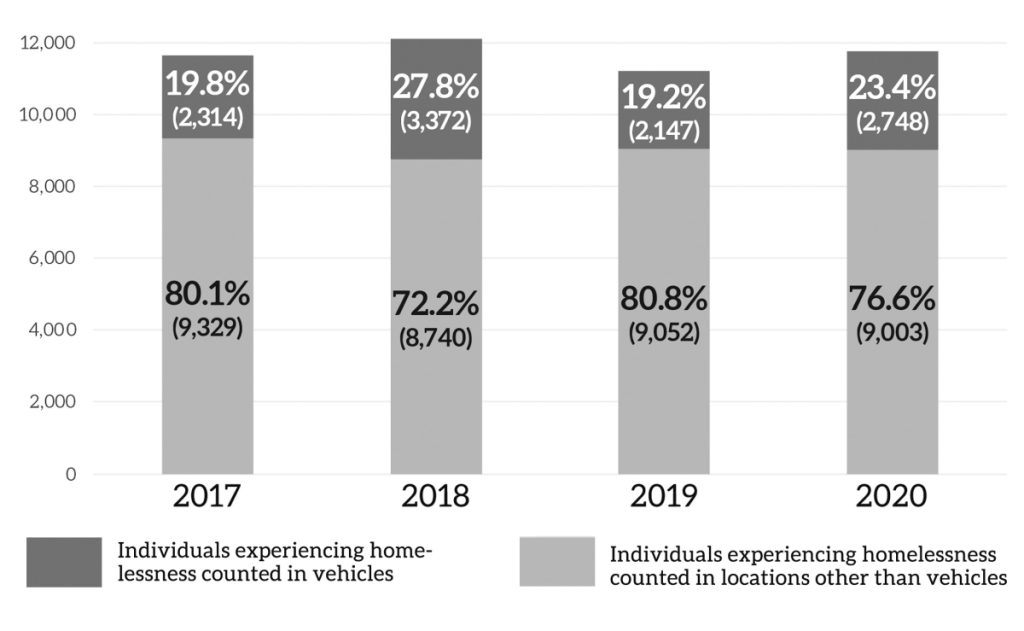

And while people living in their vehicles have long constituted a large percentage of the people living on the streets without formal shelter, only in recent years have local governments put resources behind outreach. Programs that allow them to park legally? Those are especially few and far between.

That appears to be changing.

In 2022 and 2023, different levels of government in the Puget Sound area and beyond moved to create new options for vehicle residents, with a particular focus on places where they can park safely and access services.

The King County Regional Homelessness Authority awarded $1.9 million to the Low Income Housing Institute to create a safe parking program; Pierce County formalized a pilot program to create rules around safe parking; the city of Bellevue put out a call for service providers to set up a program in the city limits; Vancouver, Washington, established a parking program as the pandemic raged; and the state Legislature heard from a working group trying to create solutions for people living in their vehicles.

This kind of public policy energy is new and perhaps a response to what appears to be a significant rise in vehicle residency seen across the country as people were displaced during the pandemic, said Graham Pruss, vehicle residency researcher and co-founder of the National Vehicle Residency Collective.

It meant that new people — some of whom don’t strictly identify themselves as experiencing homelessness — were out on the streets and visible, a phenomenon aided by moratoriums on parking enforcement, ticketing and the seizure of vehicles, Pruss said. Motorhome sales hit the highest levels in recent years in 2021, and the concept of living in one’s vehicle entered the cultural consciousness in new ways with the release of the film “Nomadland” in 2020 and the rise of #vanlife.

Policymakers are noticing and listening, Pruss said.

“For me, one of the most exciting things about what we’re seeing is that there’s finally a shift from seeing vehicle residents by this very standard binary of homed or homeless. What we’re seeing is many vehicle residents are finally being heard when they say, ‘This is my home. I need a place to live in my home to be able to not get tickets, to have access to water and garbage and keep my kids in local schools,’” he said.

The forced mobility created by parking rules can make it difficult to help vehicle residents, because they can be hard for outreach workers to find consistently, Pruss said. That makes programs like safe lots all the more important. The lots provide people somewhere they can legally stay so that they have some sense of stability.

Safe parking programs aren’t a new concept, but, outside of religious institutions that have more flexibility over the use of their properties under state law because of their mission, the programs haven’t taken off. Most of the safe parking that has been allowed doesn’t accommodate larger RVs, focusing mainly on personal vehicles. Pruss estimates only about 50 parking spaces for RVs serve a population that numbers in the thousands.

But local governments are trying to fix that by responding to the needs of vehicle residents and their demands on public space.

Nicolas Quijano is the homelessness outreach program manager for Bellevue, one of the cities that is trying to build a safe parking program. The city recently released a request for proposals (RFP) seeking a service provider that could operate out of the Lincoln Center, a property currently in use as a traditional shelter run by Congregations for the Homeless. However, that program will soon move to its new permanent location, opening up a space with amenities like bathrooms, laundry and ample parking.

Importantly, Quijano said, people’s priorities align when it comes to safe parking, even for housed people who are focused on their own perceived lack of security and don’t want to see vehicle residences on the street.

“A safe parking program is a solution for everyone, even for people for whom that’s a primary concern,” Quijano said.

In developing the RFP, Quijano looked for inspiration in existing sites at churches such as the Overlake Christian Church and Washington United Methodist, as well as the Safe Parking Zone developed by Vancouver, Washington. That city established a program at the Evergreen Transit Center during the “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order issued by Governor Jay Inslee, which aimed to keep people in their homes to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Farther afield, in San Diego, California, policymakers also contributed lessons for the Bellevue team.

The goal is to create a client-centered model that provides stability and helps people move into permanent housing, Quijano said. Something that helps set people up for success is ensuring that the program facilitates a shared sense of community.

“Organizations that have talked to me about struggles talk about putting them in an industrial area. Those people feel isolated and not connected and not having connection to basic services,” Quijano said.

In Pierce County, safe parking programs have largely been run by Homeward Bound, a nonprofit based in Puyallup. The organization has been around since 2007, said Paula Anderson, Homeward Bound’s executive director, and operates the only daytime center for homeless adults in east Pierce County.

It was, once again, the pandemic that threw the doors open to a safe parking program. Federal money flooded into state and local coffers, allowing the organization to become the second to open up a safe parking program complete with showers, laundry and meal service.

So far, the organization runs five sites that contain 32 spaces but cannot accommodate RVs. Homeward Bound brings people in through a referral line and runs background checks — people with arson or sexual offenses in their background are not welcome at the site, nor are people with recent Class A felonies.

Anderson’s reasonably sure that the sites have already saved lives.

One woman living with diabetes needed to have her foot amputated after it became infected. However, the client had a dog that she would have had to give up if she had been living on the street. She entered a safe parking program, and the other residents were able to arrange care for the dog so that it would be there when the woman was released from the hospital.

The people who the programs serve tend to be older, often in their late 40s and early 50s. Anderson refers to this as the “gray tsunami” of people priced out of their homes later in life.

“Their last safe place is their vehicle,” she said. “We’ve had probably close to 250 to 300 people through the safe parking over the course of the last two and a half years that we’ve had it up and running.”

In 2021, the Pierce County Council signed off on a plan to end street homelessness, once again paid for, in part, by the infusion of federal coronavirus funds. That meant finding solutions for people living in their vehicles, said Heather Moss, director of Human Services with Pierce County.

The county created a pilot program in 2022 that aimed to test rules around parking programs such as how many vehicles are allowed at a site and the required amenities, with slightly different provisions for religious institutions versus other nonprofits.

The county streamlined those processes and made the program permanent through an ordinance adopted in December 2022. The goal is the same as with other parking programs in the region: provide a safe place to park, connect people with services and get people off the streets, Moss said.

“We counted in … that time that we had approximately 400 or so individuals living in cars [in the point-in-time count]. If you think about the 30 slots now, even if we’ve got two or three people living in those cars, it’s still a far cry,” Moss said.

The biggest factor of what the county can provide is funds. Federal money is waning, and Pierce County officials are figuring out what priorities get funded next. Mostly they’ve tried to use federal money toward one-time costs, like a hotel purchase, or temporary programs.

It’s good to see the energy around these programs and thought going into providing services to vehicle residents, Pruss said, but the state still lacks some fundamental information about who all is out there and what they need. That’s why advocates are pushing for a statewide needs assessment — basically a survey for people living in vehicles — that, importantly, doesn’t actually mention homelessness.

That doesn’t mean parking programs and services for people living in vehicles should pause while the needs assessment moves forward, however. To a large degree, policy makers have access to solutions that work — it’s about growing them to scale.

But the current climate is allowing for a rare commodity in the homeless services field: optimism about the model.

“I’m hopeful! It’s good, it’s good. The fact that the conversation is happening is good. The fact that people are seeing this as a need is good,” Pruss said. “Now is when we need to open our ears and listen to people who have lived experience who are in their vehicles and ask what do you need? What can help you? Where can we meet you at? And not assume that the programs or services that we think will be best meeting their needs at all.”

From Lampi’s perspective, safe parking programs could be “remarkably effective,” but he doesn’t like the fact that government entities are behind the current pushes.

“The way they could have their own funds would be to do a cooperative, for-profit endeavor. It doesn’t have to be huge, but to get something started like that that was an economic engine for the community that would take the government out of it,” Lampi said. “I don’t want to work with the government. … They’ve done nothing for the people.”

This article was produced in partnership with Real Change News, where Ashley Archibald is the editor.

Ashley Archibald

Ashley Archibald is the editor of Real Change News, a nonprofit journalism outlet covering economic and social justice issues in Seattle and beyond. She can be reached at editor [at] realchangenews.org and on Twitter at @AshleyA_RC.