Before opening her swim school in Seattle, Chandrika Francis worked with students at a New Orleans high school. They told her that when the levee failed and Hurricane Katrina flooded the city, they didn’t know how to interact with the water.

“Hearing again and again all these stories of being trapped on the roof and having to float on things. Being in these really dire emergency situations, even if you knew how to swim would be terrifying,” Francis said. “Folks of color are getting direct hits from climate chaos that includes rising sea levels and floods.”

And, climate change chaos is manifesting in Seattle through its new sweltering summers.

As people turn to urban lakes and rivers to seek some relief, drownings are spiking to totals never seen before. The temperature shift compounds existing environmental and social justice issues: Not only are communities of color living in heat islands with limited cooling infrastructure, but they have also been historically excluded from places where they would have opportunities to learn how to swim. Meanwhile, the lifeguard shortage hitting the region means there are fewer chances to swim in safer, monitored settings.

A spike in drowning cases coincides with Seattle’s yearly bouts of heatwaves that have come each summer since 2019. Over these last few years the number of people who drowned has doubled – averaging 30 preventable deaths a year. And of the 12 people who’ve died so far this year, many drowned during the unusual spring heatwave in May, when fresh snowmelt still flowed through rivers and into lakes, increasing risk of hypothermia.

“As climate change impacts our region, that’ll be something that we collectively need to come to grips with, that warmer weather is happening earlier,” said Tony Gomez, program manager with Seattle & King County’s Violence and Injury Prevention Unit. “It’s certainly an equity concern.”

Gomez analyzes trends in Seattle’s drowning cases through numbers he collects from medical examiner records. He looks at demographics and factors, like toxicology and location, in five-year summaries.

Lake Washington is the deadliest for swimmers and recreationalists in Seattle who take to open water. And, its shorelines in South Seattle bump up to the most racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods in the city which run parallel to Lake Washington. Black residents here are 2.5 times more likely to drown than White residents.

In his summary for 2018 to 2022, he also found that people who are Asian, Pacific Islander, and Indigenous make up 17% of drowning deaths.

These statistics stem from racism and violence that persisted at public pools in mid-century America. Seattle was no exception.

“It’s not just the physical fear of water, it’s really this intense history,” said Francis, who developed trauma-informed workshops at Oshun Swim School centered around healing. “We might not know the details of it, but we still feel and experience it.

Reclaiming Water Spaces

When the renovated Colman Pool in West Seattle opened in 1941, the recreational director ordered pool attendants to only allow White people to swim. He called it a solution to overcrowding.

Densho Archives, an organization that catalogs Japanese American stories, preserved the moment through an interview with Seattle-born Yosh Nakagawa. He tried to use the pool, but while the discrimination was subtle, it was effective, he said. When Nakagawa and other Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated to concentration camps, Black students from the University of Washington protested for three years before finally getting entry to the pool.

This exclusion still often manifests in public institutions and recreational spaces for people of color, because they don’t see themselves represented there. It’s something Nina Wallace, who now works at Densho Archives, saw when she was a lifeguard for eight years. She watched interactions unfold at the indoor pool in the Central District that still give her pause.

“Sometimes, I think it’s a question of what is the environment that is being cultivated in this space? Are the lifeguards all White and always yelling at the Black and brown kids for throwing noodles around or things like that? It’s not going to be like an explicit rule that, you know, people of color are not welcome at this pool,” she said. “But maybe that’s the message that people are receiving.”

The lifeguard shortage is also causing some beaches to close early or not offer supervised swimming hours. Three Seattle beaches don’t have any lifeguards this summer: Madison, Seward, and East Green Lake beaches. Many beaches are unattended after 7pm, despite the sunset being nearly two hours afterward.

While lifeguard shortages have been blamed on pandemic-era closures and restrictions, nationwide only 6% of lifeguards are Black. The low numbers highlight the limitation of who can enter this workforce because of inequitable access to basic water skills.

Changing Policies for a Safer Future

To keep people safe in open water, policy change increasingly proves to be the most impactful tool for water competency.

Pilot programs like Swim Seattle are trying to remove barriers for the next generation by offering free lessons to those who may not be comfortable in water or can’t afford aquatic-related classes. The first cohort also includes parents who are addressing their fears of water as well as learning about skincare and haircare when swimming.

The program works closely with community groups like No More Under – a nonprofit dedicated to equitable swim access and tools. Chezik Tsunoda founded this group after her three-year-old son’s drowning. Through her devastating experience, Tsunoda learned that drowning is a leading cause of death of children, and for those who survive, it can leave children with long-term neurological complications.

Tsunoda advocated for House Bill 1750, and worked with Mill Creek Representative April Berg at the State Legislature who ensured its successful passage. Known as Yori’s Law, the legislation commits the state to providing swim education and tools to all children regardless of race and socio-economic status.

Yori’s Law is based on awareness, so Tsunoda is now pushing for funding for a drowning prevention curriculum in schools. That way if children get into a life-threatening situation in water, they know what to do – just like they have learned about the drop, cover, and hold positions during earthquakes.

“You buckle your seatbelt every time you get in a car, right? It’s second nature,” Tsunoda said. “We are surrounded by water, and we recreate around water. It’s sad to me that we don’t have the awareness to not only teach our children, but also, the adults.”

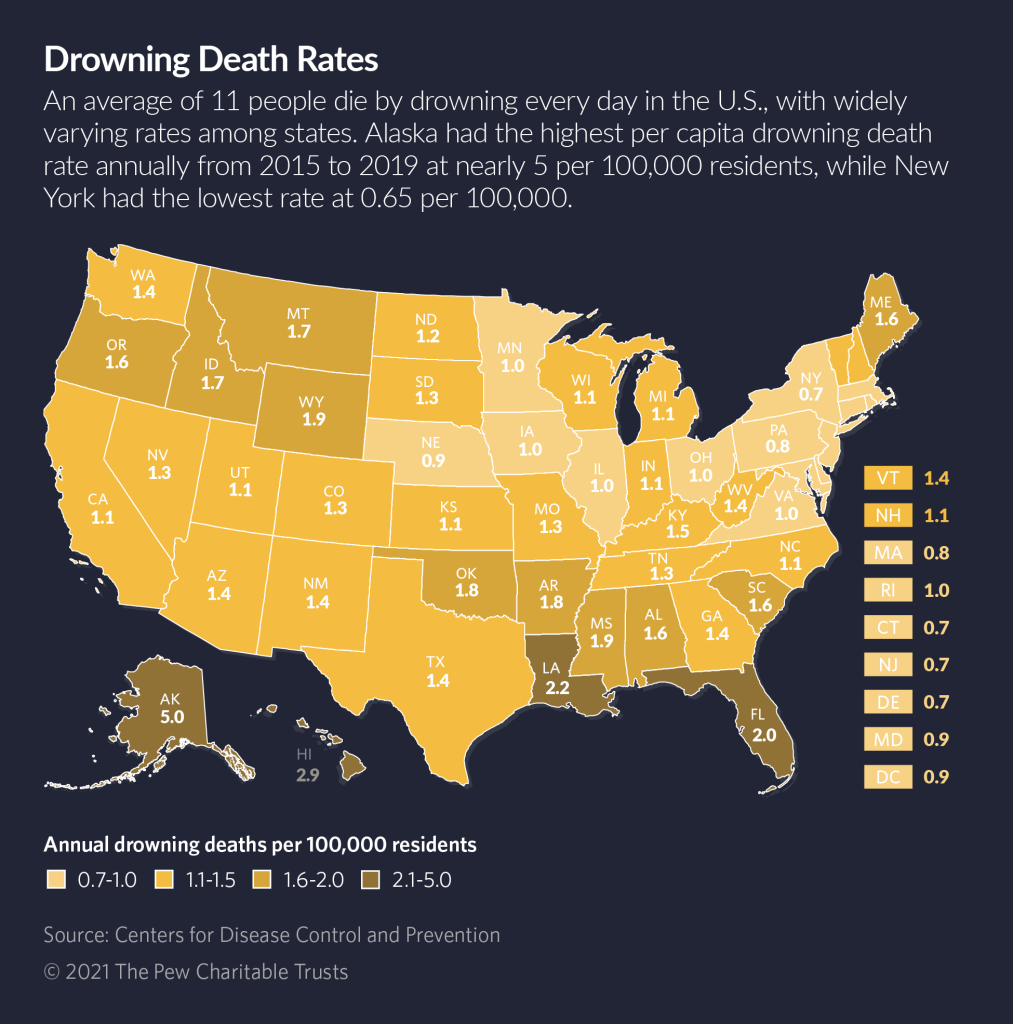

It’s not just education that needs to be revised by policy, but stronger regulation needs to be written for urban beaches. States that regulate beaches are associated with lower rates of drowning, according to research from the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital. New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey have regulations that mandated reviews of beach design and water clarity levels. These states have half the number of drownings in open, natural waters than Washington.

Conversations about having such regulations in Washington are now just starting. State leaders cite financial restraints, but they are still paying for it retroactively. The drowning cost burden statewide each year is $1.4 billion which includes medical care and other expenses, Gomez said.

That’s money that could be spent up front on prevention while saving lives – because swim skills are essential for frontline communities of the climate crisis, the same communities who are rebuilding their relationship with water.

“So many things about the climate catastrophe we’re in, it’s so daunting and complex, but with swimming, it’s straightforward,” Francis said. “You need the time and access to a safe space to learn these skills and then you have it for the rest of your life.”

Urban Swimming Resources

Swim and Safety Programs:

- Oshun Swim School

- Dance & Splash Events with Inspired Child

- Swim Seattle – Parks

- Swim Lessons | YMCA of Greater Seattle

Swimming Locations:

- Swimming Beaches – Parks | seattle.gov

- King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks – Swim Guide

Water Quality for Swimming Locations

- About the Lake Swimming Beach Program – King County Lake Swimming Beach Bacteria and Temperature – King County

Ashli Blow

Ashli Blow is a Seattle-based freelance writer who talks with people — in places from urban watersheds to remote wildernesses — about the environment around them. She’s been working in journalism and strategic communications for nearly 10 years and is a graduate student at the University of Washington, studying climate policy.