Facing record-breaking demand, offshore wind could balance the state’s clean energy portfolio, covering gaps in peak winter months.

When Governor Jay Inslee announced the Blue Wind Supply Chain Collaborative alongside local industrial and port leaders in October, it was clear Washington State wanted offshore wind manufacturing jobs. What was less clear is if the state actually wanted to see the wind turbines spinning off its shores.

Washington is the last West Coast state or province to make a leap into offshore wind, but leaders are still hesitant to move fast on advancing projects. That’s because they share the concerns from coastal communities and tribes about impacts to ocean fisheries and harming wildlife. As they search for a just energy transition, a recent market analysis makes a compelling economic case that offshore wind can meet the high energy demand while aligning with the state’s ambitious climate goals.

“[T]here are important, unanswered questions about offshore wind in Washington specifically,” Governor Inslee wrote about the collaborative. “We need to better understand potential impacts to the ocean environment and fisheries. Treaty-reserved rights must be protected. The technology must also pencil out to be profitable, and there are substantial costs to transmit energy back to shore.”

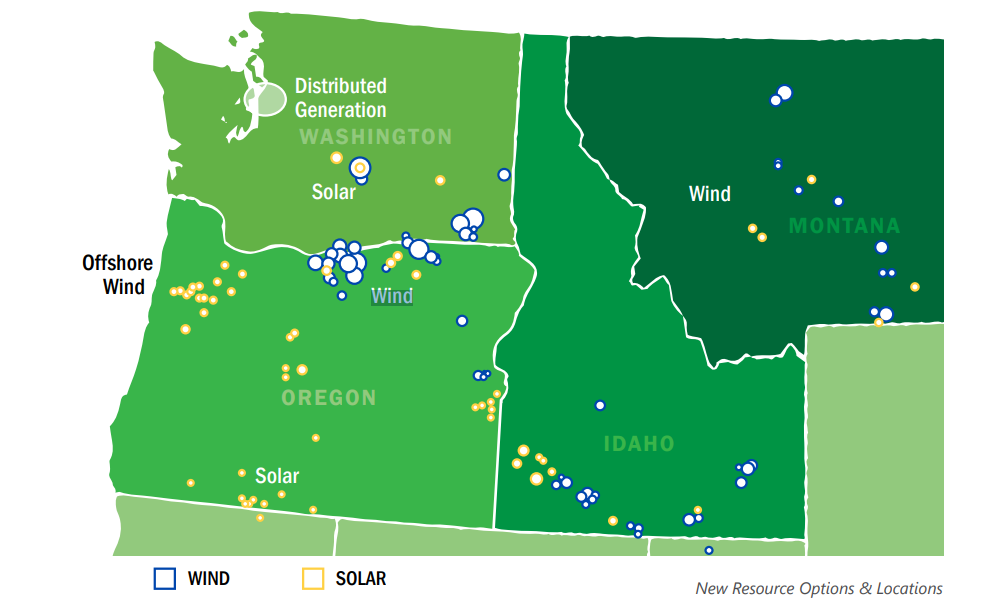

The reason offshore wind could be key to Cascadia’s energy portfolio is because climate change is hurting the reliability of hydroelectric power that has traditionally been the region’s top power source. Drought conditions are reducing power output at dams, and extreme temperatures are contributing to higher energy demands from residents and businesses. Solutions like solar can help cover gaps, but it will take an energy portfolio of diverse renewable resources to meet the reliability and generation of hydropower. Without that mix, public utilities are left to buy energy on the open market to cover shortfalls — this is both expensive to ratepayers and has been an excuse to keep polluting fossil fuel power around.

It’s something that happened this year when low precipitation coincided with high energy loads in Seattle, triggering a surcharge as Seattle City Light bought more power than usual from other energy producers. To help make up for a $70 million deficit in its cash reserves, SCL instituted a 5% rate increase. It will show up on bills starting in the new year.

As Seattle experiences record-breaking energy consumption, offshore wind would help diversify the energy portfolio and prevent utilities from costly responses in the future, according to Alla Weinstein, CEO of Trident Winds, a company pursuing an offshore wind project off the coast of the Olympic Peninsula.

“The state should definitely pay a lot of attention and [look] into developing this resource, because in the process it could save a lot of money for the ratepayers,” Weinstein said. “Because the state does not have to overbuild something else in order to meet its energy and climate goals.”

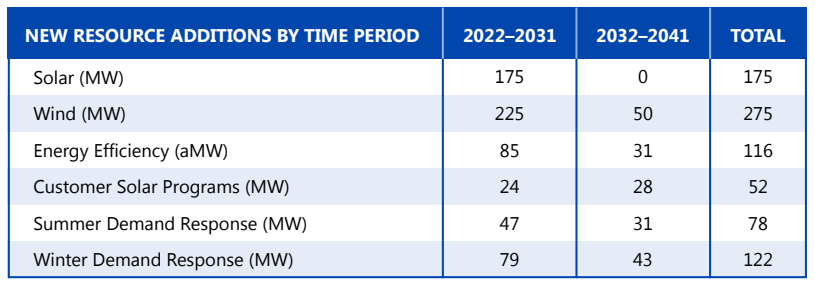

Hydropower accounts for 86% of SCL’s power mix, an energy portfolio that the utility must keep green under the state’s Clean Energy Transformation Act all while meeting increasing demand from their customers. It’s why SCL is looking to diversify its renewable energy with wind power leading new supply resources, according to recommendations in its latest integrated resources plan.

Offshore wind can take advantage of reliably strong coastal winds, providing more dependable power than inland wind turbines. Output tends to be strong in low solar months or when summer droughts sap hydroelectric generation, which currently makes up half of the state’s power.

Where offshore wind could fit into energy mixes

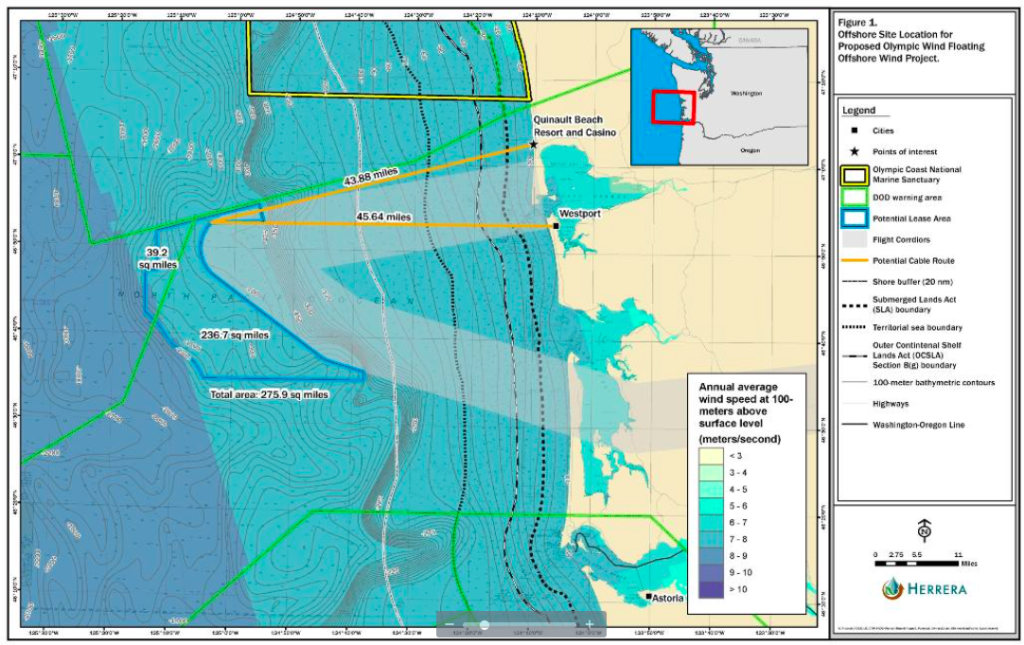

Last year, Trident Winds asked the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) for permission to lease a site for a floating offshore wind project in federal waters, located more than 40 miles off the coast of Grays Harbor, Washington. They are one of the two companies who filed a request with BOEM.

Trident Wind’s proposed project aims to build, operate, and maintain a floating offshore wind farm with a capacity of around 2,000 megawatts. That’s enough energy to power 800,000 homes, according to the company. To move the project forward with government agencies, Weinstein commissioned a study — released publicly this November — to unpack the reliability of offshore wind along Washington’s coastline.

That economic study, conducted by the firm Energy+Environmental Economics, showed offshore wind as a significant and cost-effective clean energy resource that helped balance Washington’s clean energy portfolio and climate policies. Without offshore wind, the evaluation showed that alternatives to meet the same level of system reliability would rely on out-of-state wind and could require building expensive combustion plants.

In addition to saving on construction costs, the study reveals that integrating offshore wind into the state’s energy mix has the potential to save ratepayers $5 billion in total, because of its robust generation in winter months. That’s when Washington has its highest energy demand.

Additionally, the cost to install offshore wind would be less than building more infrastructure for other clean energy technologies like solar, Weinstein said.

“So, the conclusion of the study was that between the resource and demand, and because of its availability on the west side of the state where you have the highest population, it could be a resource that the state would have a hard time to not have in its portfolio mix,” Weinstein told The Urbanist. “Offshore wind is very well-aligned with the demand profile of the state of Washington.”

That alignment is something that Governor Jay Inslee’s office agrees with, but instead of immediately incorporating it into the state’s energy mix, the focus of his office has been on investing in the advancement of offshore wind technology and generating manufacturing jobs.

In his October announcement, Inslee emphasized the regional tech sector’s ability to solve how offshore wind can operate in the Pacific Northwest’s deep waters. Unlike the East Coast, where turbines are typically fixed to foundations on the ocean floor, those off Washington’s deeper shores will rely on floating platforms.

“We’re developing new technology to have a submerged, buoyant platform. We’re designing it right here,” Inslee said. “To put this into context, what Louisiana has in the oil industry, we could have in offshore wind. And I’m less worried about wind spills than I am about oil spills in the Gulf.”

Addressing challenges of offshore wind

Offshore wind adoption in Washington faces challenges beyond technological readiness, with a laundry list of concerns: potential impacts on commercial and tribal fisheries, the health of the marine ecosystem, and the cost to transmit energy to shore. Additionally, the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary covers 40% of Washington’s coast, limiting ocean space for renewable energy projects.

“We have a lot of siting challenges in the state and have certainly heard from tribal nations in Washington, particularly located along the coast and coastal communities and fishing communities — a lot of concerns about what offshore wind could mean,” said Nora Hawkins, senior energy policy specialist at the Washington State Department of Commerce. “Those conversations haven’t yet started.”

A couple of weeks after Inslee’s announcement, the Department of Commerce — the agency that oversees the state energy strategy — announced a new project to engage federally-recognized tribes, coastal communities, fishing and labor groups, and several other stakeholders about potential offshore wind development and its impact on culture and the environment.

The project’s primary goal is not technical development but rather the creation of a communication framework for rural communities. This is essential as these communities sometimes feel that their natural resource extraction efforts benefit larger metropolitan areas at their expense.

This Washington coastal community engagement project coincides with growing resistance in Oregon, where electric utilities are considering offshore wind farms in two locations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

“[In Oregon], there was a lot of conversation about the need to ensure that that power serves coastal communities, which are often farther from sources of generation [and] potentially have less reliable power,” Hawkins told The Urbanist. “So, a desire to see if transmission is coming onshore to make sure that that electricity goes into local communities and doesn’t just go via a transmission line over their heads.”

Coastal communities in Washington are already being creative to keep money made from renewable energy. In Grayland, the Coastal Community Action Program worked with General Electric nearly 10 years ago to install four turbines and sell its generated power to their local utility. Ever since, the action program has used revenue to support different services, like housing and job training in the Aberdeen area. But that may not be enough when it comes to a large-scale project.

It’s why government workers say they want to understand the perspective from those who live along the coast and get ahead of potential problems before they jump behind a proposal.

“[The project proposal] signals a shift in the use of ocean space essentially,” said Lisa Pfeiffer, economist with NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Sciences Center. “BOEM has been trying to minimize fishery impacts by avoiding areas where there’s conflict with lots of fisheries, but there’s still a lot of concern among the fishing industry.”

Pfeiffer is part of a team responsible for the conservation of fisheries, marine mammals, and habitats. They’ve been helping BOEM with leasing and permitting for potential offshore wind projects. She also accounts for the bigger picture, going beyond impacts to ratepayers, like implications that marine infrastructure could bring on fishery revenue and subsequently coastal town economies.

From her perspective, offshore wind isn’t an urgent need just yet, and the Department of Commerce suggests that the practical integration of offshore wind into the energy mix may take at least 20 years. But project developers like Weinstein believe concurrent progress in infrastructure discussions, community engagement, and economic considerations help prevent extreme supply and demand imbalances that could come in the future.

“There’s only so many resources you can tap into,” Weinstein said. “And you have to look at that technology readiness and what would be now, what would be later, and how the state is going to address its electrical system needs and the climate objectives.”

Ashli Blow

Ashli Blow is a Seattle-based freelance writer who talks with people — in places from urban watersheds to remote wildernesses — about the environment around them. She’s been working in journalism and strategic communications for nearly 10 years and is a graduate student at the University of Washington, studying climate policy.