The stated goal of Kitsap County’s 2024 Comprehensive Plan Update is to maintain the county’s rural character by directing “the majority of growth toward urban areas” and supporting denser housing around transit. And while the County has some progressive ideas, the Comp Plan’s updated zoning rules don’t go far enough to prevent ongoing sprawl and increased population into the far hinterlands of the county.

Excluding Kitsap’s four incorporated cities – Bremerton, Port Orchard, Poulsbo, and Bainbridge Island – unincorporated Kitsap County is primarily rural. 59% of county residents live in rural zoned areas and the majority of housing built in the past 11 years was built in areas zoned rural. If Kitsap wants that to change, it needs to make meaningful zoning changes, but the draft 2024 Comp Plan falls well short. Outside of three small “Growth Centers” (Silverdale, Kingston and Central Kitsap), virtually all of the Urban Growth Areas (UGAs) will be zoned exactly as they were in 2016, the last time the plan was updated.

To be clear, zoning rules do not decide where homes will be built, developers do. Zoning sets rules about where different types of housing might/can’t be built. Developers decide where to build based upon where it makes sense (aka makes money) based on a variety of factors: zoning, tax abatements, minimum and maximum density, required parking, etc. Smart zoning incentivizes developers to build in smart places.

Kitsap County is disadvantaged in attracting developers because of its low housing prices, relative to King or Snohomish counties. Median home prices are $550,000 in Kitsap, $775,000 in Snohomish and $935,000 in King County, according to Northwest Multiple Listing Service. Thus, a developer can sell an apartment building in Bellevue or Edmonds for much more money than an identical one in Silverdale or Kingston. So if Kitsap County wants to encourage developers to build here, the incentives have to be market-oriented and smart.

Do what you’ve always done, get what you’ve always got

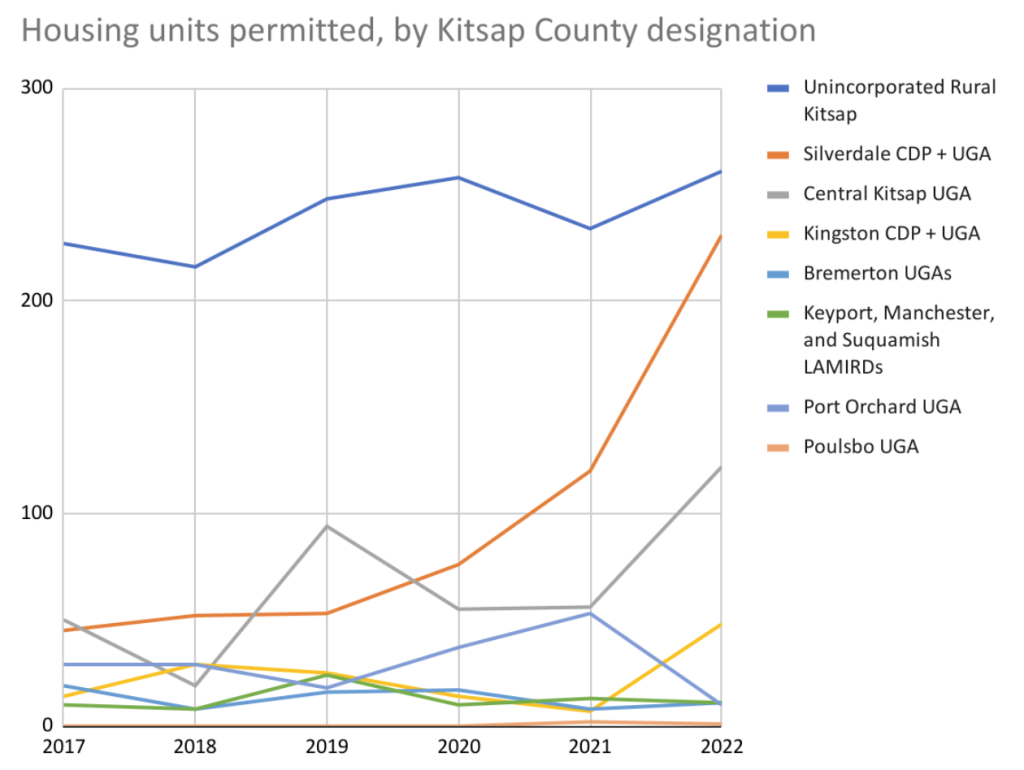

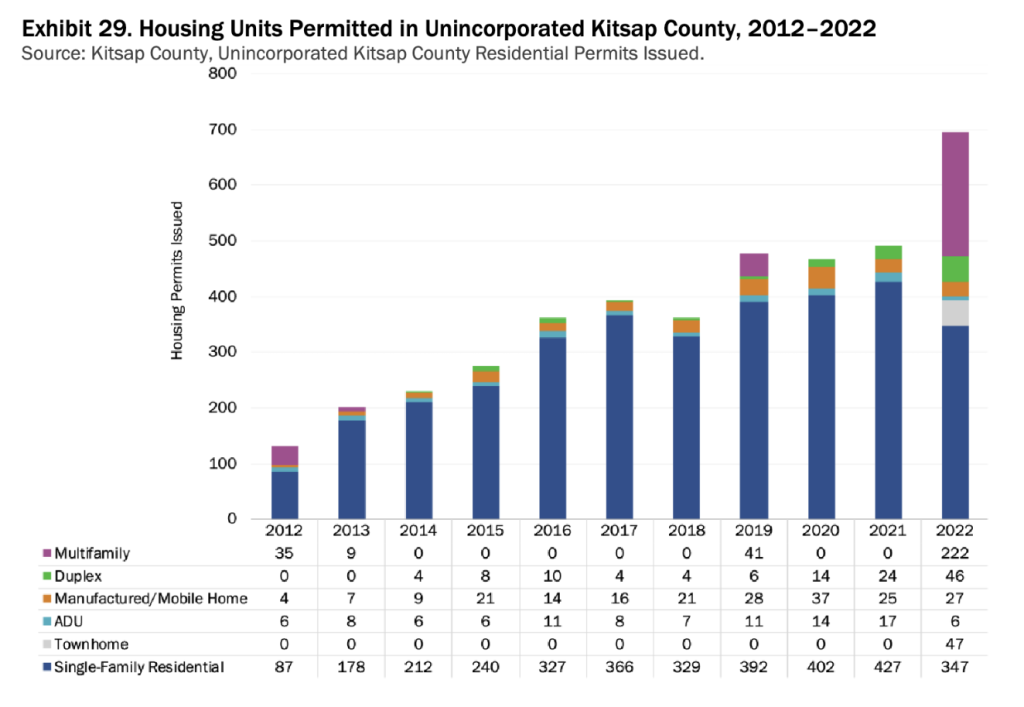

The 2024 Draft Comp Plan sets a goal: 85% of population growth in Kitsap between 2024-2044 will occur in the county’s UGAs, and only 15% in rural zoned land. But in the 11 years 2012-2023, only 48% of new homes were built in the UGAs, 52% in rural areas…and it gets worse.

Over that same 2012-22 time period, only 7.5% of new housing built was multi-family. For comparison, the City of Bremerton built 54% of its new units as multi-family housing in 2013-2019, according to its Buildable Lands Report. Only 93 accessory dwelling units (ADUs) have been built in the unincorporated county over those 11 years.

The 2016 Comp Plan called for 77% (61,989 of 80,438) of new residents to live in Kitsap’s Urban Growth Areas. But since that time, only 48% of homes have been built in UGAs.

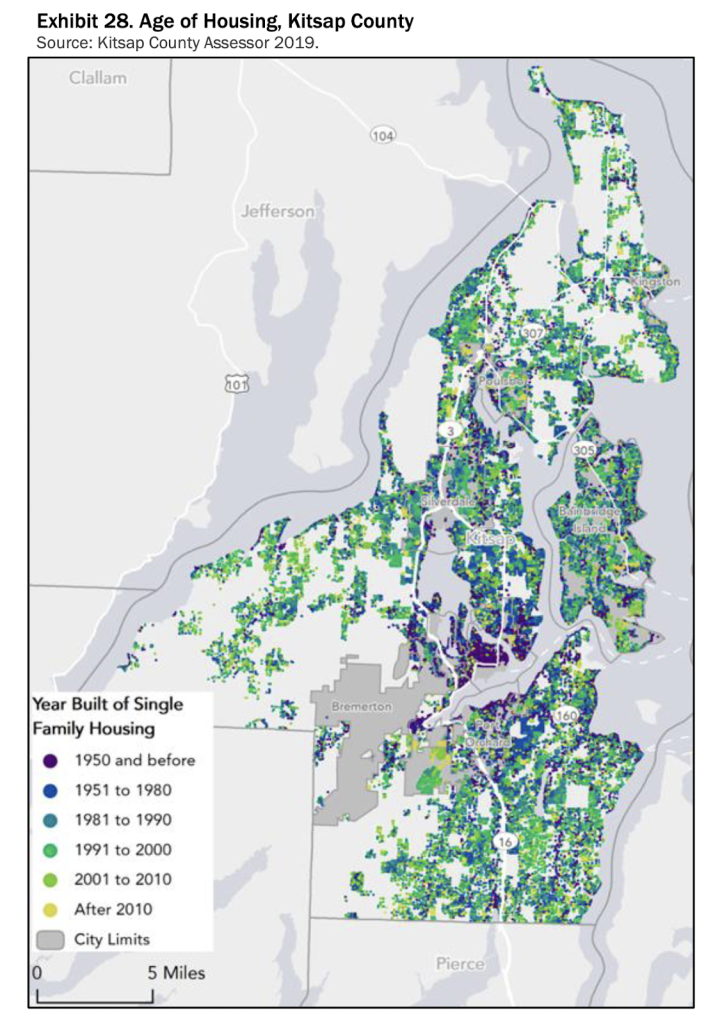

Despite what the County might hope for, Kitsap is building almost exclusively low-density housing in rural and suburban areas. Almost all the new growth occurs on newly chopped forest. If the trend continues, the County has no chance of addressing its bold stated goals regarding climate, traffic, loss of forest and farmland.

If 20,000 trees fall in a Regional Growth Center, is it really a forest?

It should be noted that the the county’s 2021 Buildable Lands Report reports Kitsap’s UGAs growing faster (7.6% over 6 years) than the rural area (4.5%), which contradicts the data above. Part of the discrepancy is the county’s tendency to permit suburban growth in rural areas and then reclassifying that land as UGA. Instead of filling in with density, Kitsap’s UGAs sprawl outward into farms and forests. Despite moving the goalposts, UGAs fell short of “policy target of 76% urban for new growth,” stating “unincorporated UGAs, growth from 2013-2019 was… between 1% and 50%.”

The phenomenon of moving borders to accommodate “urban” sprawl can be seen clearly in the two alternatives for Silverdale Regional Growth Center (RGC). Apparently unable to achieve growth goals within its boundaries, commissioners will choose whether to sprawl Silverdale RGC to the east or the west, designating hundreds of acres of doomed forest for future housing.

The problem of unbuilt rural lots

Yet another challenge to dense growth in Kitsap County is a deep stock of unbuilt lots, most in rural areas. Building out these lots not only costs more to build because they lack sewers, sidewalks and broadband, they also contribute to sprawl, as future residents will have to drive much farther to schools, jobs and shopping.

Many of these rural lots were created in the early 1990s. Between the 1990 passing and 1994 effective date of Washington State’s Growth Management Act, which greatly restricted the ability of rural landowners to subdivide their land, there was a rush to subdivide before the deadline. According to the county’s Parcel Data, 13,895 undeveloped lots still remain. At one house per lot and 2.5 humans per house, that’s enough lots to accommodate all of unincorporated Kitsap County’s growth through 2050.

County leaders are powerless to prevent development on these unbuilt lots. The County simply can’t prevent a landowner from building on a lot they own. So the 2024 Kitsap County Comp Plan must use every tool to incentivize new homes to be built by increasing density limits, limiting or eliminating parking minimums and streamlining permitting so developers choose to build in UGAs.

Bright spot: Urban Growth Centers

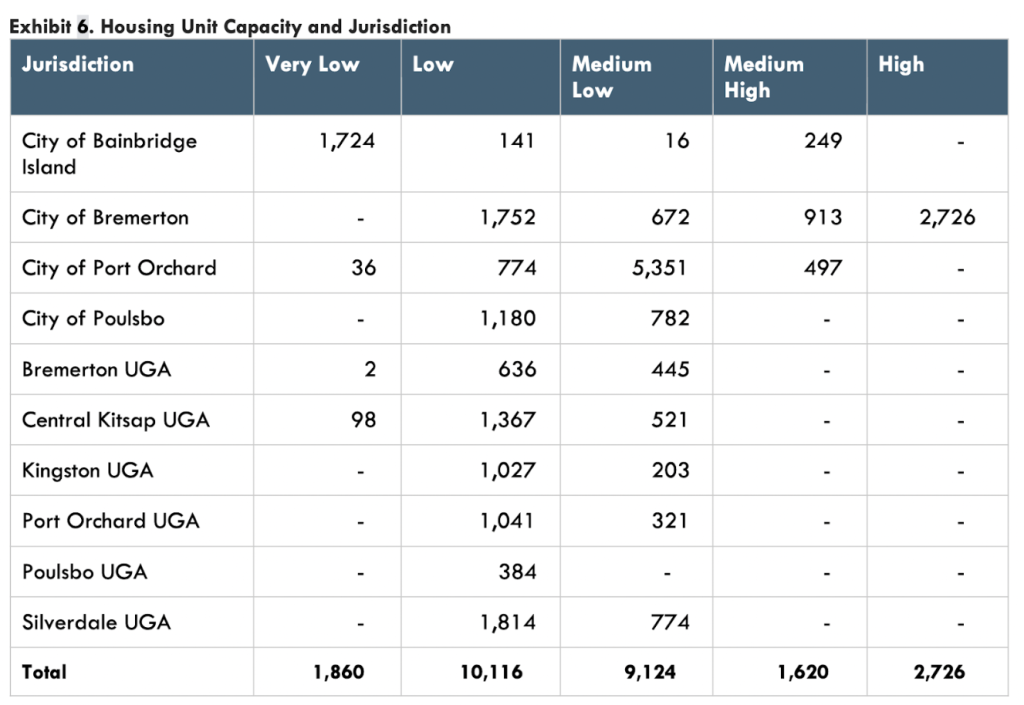

In fairness, the County is significantly upzoning three small Growth Centers. As of 2019, unincorporated Kitsap County disallowed any housing zoned higher than “medium low” density.

The 640-acre Silverdale ‘Regional Growth Center’ would permit more mixed-use, multi-family and no-height-limit housing including on underutilized Kitsap Mall parking lots. Two additional Growth Centers including Kingston (183 acres) and McWilliams (162 acres just north of City of Bremerton), will permit increased density and higher building height maximums. Those Growth Centers do provide significant potential housing growth.

But those three Growth Centers consist of fewer than 1,000 of Kitsap’s 285,000 acres. And most of the scarce areas where higher-density uses would be allowed are already built out. UGA land surrounding the Growth Centers remain zoned only for low-density housing (1-9 dwelling units per acre).

All that means developers have very few opportunities to build multi-family homes near transit or within walking distance to urban amenities. The scarcity of lots available for high-density development pushes up the prices of the land and makes those housing projects less likely to pencil out. Developers will continue to conclude that it’s more profitable to chop down virgin forests for subdivisions rather than build walkable, transit-oriented housing.

How it might be different

Kitsap County could improve this with modest solutions that other communities have successfully executed. Here’s some ideas.

- Adopt HB1110 ‘Missing Middle’ rules in Kitsap UGAs – Three of Kitsap’s cities will soon be required to permit multi-family housing and ADUs in single-family zones. Kitsap’s UGAs should adopt these rules to build up existing neighborhoods.

- Allow very high density buildings in more areas. Permit and incentivize buildings with 250+ apartments built 80-feet-tall like those common in Tacoma, Seattle and Bremerton. Unincorporated Kitsap has exactly zero of these types of buildings and, in the Comp Plan, only Silverdale allows them. Just one 300-unit building would be equivalent to 20% of the unincorporated County’s yearly projected growth.

- Build density walkable to high-volume transit routes. The suburbs can support bus systems, but only if people live close enough to the bus stops. Expanding the McWilliams County Growth Area just north of Bremerton would allow new residents to tap into existing, high-frequency bus routes on Wheaton Way (SR 303).

- Ferry-Oriented Development – Washington State’s proposed “Transit Oriented Development” bills at the legislature continue to exclude ferry zones. That’s a mistake. Kitsap County should permit parking-limited housing near the for car-free ferry commuters near Southworth and Kingston. Incorporated Bainbridge Island should do the same.

- Merge bus systems: Kitsap County has three bus systems: Kitsap Transit, Worker-Driver (a KT-operated legacy of WWII US Navy transportation) and several school district bus systems. Merging would create a single, stronger bus system. The new service could serve both students and shipyard workers by coordinating start times at schools and the Base. Vehicle miles traveled would plummet if parents could rely on safe, reliable schools buses for student drop off.

Kitsap County’s officials and citizens have a sincere desire to reduce sprawl, maintain “rural character” and create walkable, transit-oriented communities. And the three Regional Growth Centers made strides in that direction. But the housing zoning in the 2024 Comp Plan is simply too timid to reverse the trend of ever-spreading sprawl. Changes can still be made to the Comp Plan, but time is running out. Residents can comment on the plan until April 8, 2024.