Seattle’s misguided water hookup policies lead to unequal outcomes, effectively downzoning much of the city where fees are too high to make housing feasible.

Constructing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) is an empty promise for many homeowners in Seattle due to numerous regulatory hurdles, with water hookup fees one of the most thorny.

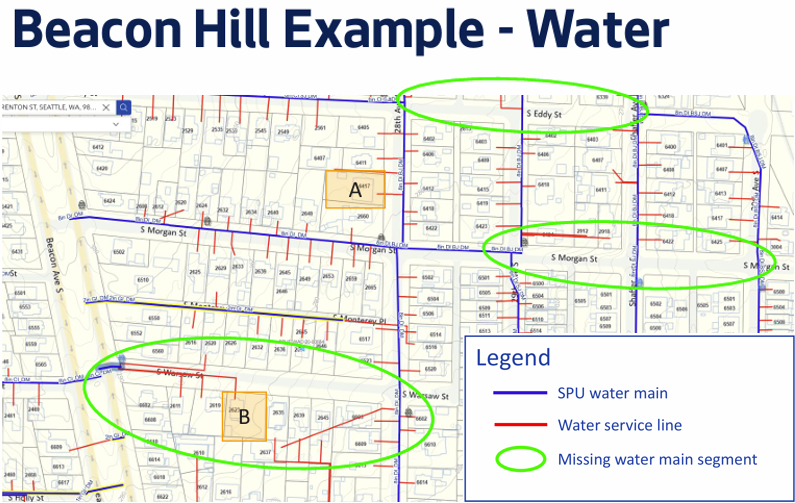

In a May 14th presentation to the Seattle City Council, Seattle Public Utilities (SPU) revealed that 400 miles of city streets lack water mains. Without a water main, new water service to support construction is denied by SPU.

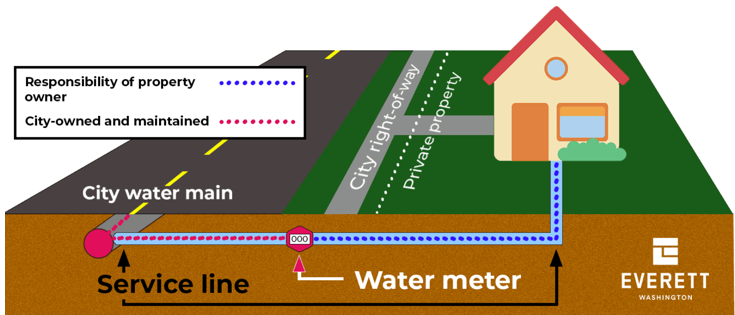

Property owners denied access to the public water system must pay for and install water main extensions as a condition for new service, which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. On the other hand, property owners along the other 1,600 miles of streets with water mains are allowed to connect to an existing water main.

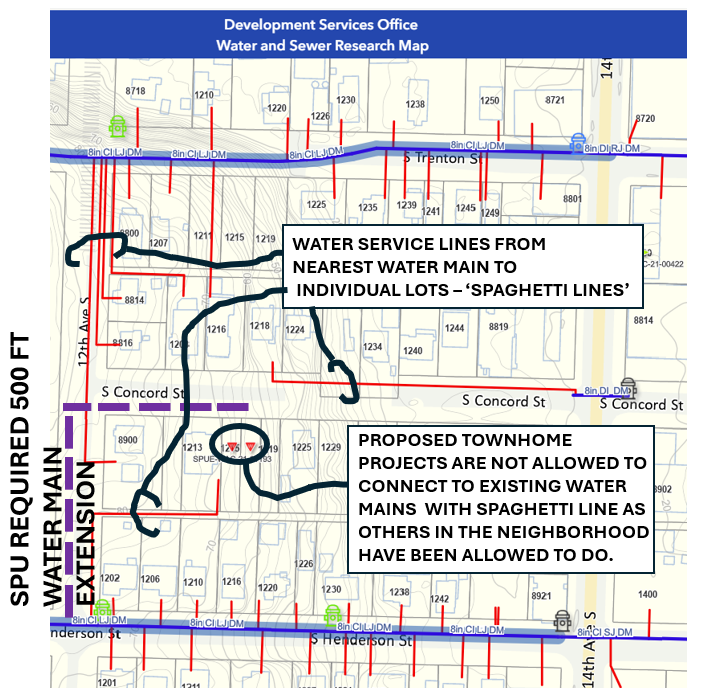

Up until the early 2000s, SPU allowed all property owners to connect to the nearest water main, up to one block away. SPU refers to these longer service lines as spaghetti lines. Allowing installation of long service lines results in fair outcomes for all property owners.

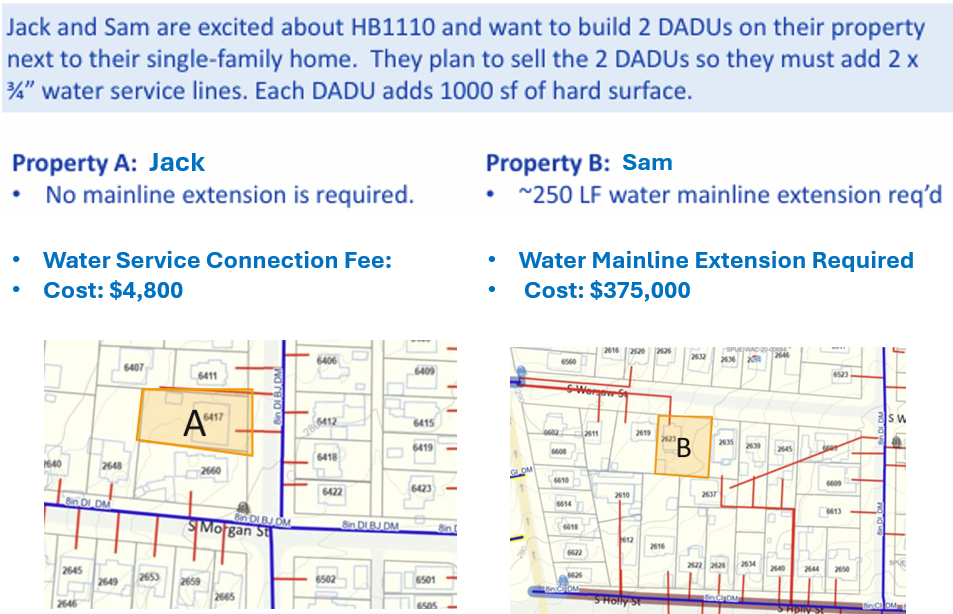

To illustrate their proposal, SPU’s presentation included a tale of two property owners, Jack and Sam. Each property owner desires to build two detached ADUs.

A water main exists in front of Jack’s Lot A, and he can obtain water service to support construction. However, Sam on Lot B is not so fortunate. They must pay for and install an eight-inch-diameter water main extension, at an estimated cost of $375,000. Sam’s requirement to achieve the same outcome is incredibly disproportional to Jack’s, and demonstrates the inequity of SPU’s current water main policies.

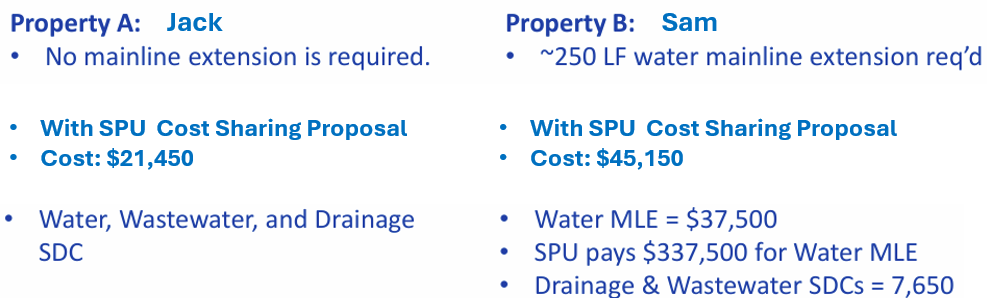

SPU’s cost-sharing proposal only a partial band-aid

SPU is now suggesting adding yet another fee: an increase to the System Development Charge, also known as a water service connection fee. Additional fees collected will be used to partially reimburse the cost for those who are subjected to the water main extension policy. This proposal is currently under review by City Council, with a vote expected during the upcoming Parks, Utilities and Technology Committee meeting on Wednesday, May 28 at 2pm.

Under this proposal, an applicant like Sam will still have to install the water main and pay the $375,000 up front for the installation. It is only after the installation that the proposed policy offers partial cost reimbursement. Even with a partial reimbursement, Sam’s main line extension (MLE) cost is estimated at $45,150 and is twice that of the costs incurred by Jack.

Furthermore, the SPU example does not reveal the $150,000 cost for removal and replacement of street pavement that Sam will incur, for which there is no reimbursement. The true cost for Sam is significant – nearly $200,000. There is no economy of scale for Sam to spread out the costs. Cost sharing or not, SPU’s policy means Sam does not benefit from the additional housing on his lot as he is entitled to per HB 1110.

The policy has the effect of zoning downsizing, taking away a property owner’s ability to reap the benefits of increased housing density.

City’s cost-sharing fund too small to meet need

SPU expects to collect an added $6.6 million in water system development charges. These collected fees are to be used for partial reimbursement for private water main installations. However, these funds will fall significantly short of that needed.

Approximately 300 permit applicants per year are issued Water Availability Certificates that include mandates for water system infrastructure improvements. Conservatively, using an average per-project reimbursement value of $150,000, the amount needed to reimburse those 300 permit applicants is $45 million. Anyone who hangs their hat on obtaining a reimbursement needs to hope they can snag some of the $6.6 million for a given year before the budgeted reimbursement funds are depleted.

With or without cost sharing, the deck is stacked against property owners without street-side water mains. There is no relief from the costs for pavement removal and re-pavement associated with trenching for a new water main. There have been hundreds of new housing permit applicants and thousands of unbuilt houses to date that have been crushed by the SPU’s policy prohibiting installation of long service lines.

Judge rules against SPU water main policy

One property owner sued the city of Seattle in King County Superior Court over SPU’s water main extension policy. She applied for one new water meter to serve a new house and new detached ADU. She requested service via a long service line, most of which was on her private property. Instead, SPU mandated a 173-linear-foot water main extension in exchange for the water meter. The estimated cost to complete the work is $350,000.

A Summary Judgement in favor of the applicant was issued on December 6, 2024, finding that the “no spaghetti line” policy of SPU is arbitrary and capricious as applied to the applicant. The court confirmed the policy is found nowhere in the city code, director’s rules, or engineering design manual, which means permit applicants are routinely blindsided by this unwritten SPU policy.

The summary findings of Judge Nicole Gaines Phelps include the following:

- Plaintiffs suffered a cognizable constitutional injury the moment the City imposed the unconstitutional condition on the water availability certificate.

- The City’s demand that Plaintiffs fund the design and installation of a water main extension as a condition of issuing a water availability certificate is an exaction.

- The city has failed to meet its burden of showing that the extension was “reasonably necessary as a direct result of the proposed development or plat to which the dedication of land or easement is to apply.” Thus, the condition violates RCW 82.02.020.

SPAGHETTI LINES ARE THE SOLUTION:

A proposed townhome project on Concord Street provides an example of how spaghetti lines are the solution. The project proponent is required to install 500 linear feet of water main at a cost of around $1 million. Even with the cost-sharing proposal, the property owner would still be required to pay around $400,000, including pavement removal for trenching and street repavement.

This project further exemplifies how the cost-sharing proposal falls short of creating pathways for new housing to be built, and how these policies effectively prevent additional housing in the impacted areas. It is a detriment to the whole community, as well as to landowners looking to add an ADU or multiplex. SPU must re-establish the use of long service lines commonly allowed in other cities.

SPU’s reason to deny long service lines is the cost for future homeowners to maintain. This could be addressed with a cost reimbursement program to assist property owners for repair. Preventing much-needed infill housing simply to prevent a future maintenance backlog hardly seems the way to address the issue. Most homeowners would much prefer to pay for spaghetti-line repairs after getting decades of use out of a property than being coerced into paying for unneeded water main upgrades on the front-end before they ever can see housing built.

SPU has requested the council approve a $950,000 appropriation to hire six new employees to manage the water main cost-sharing program. A more streamlined and cost effective solution is for SPU to hire two new employees for customer service, to manage maintenance and repair of long service lines. Relieve homebuilders of the burden to pay for and install water main extensions, do not increase the system development charge. Instead, use the rest of the $950,000 fund to reimburse property owners for the repairs.

Removing the restriction on long service lines will open the tap to allow the permitting pipeline to flow for hundreds of housing projects clogged in the system due to SPU’s policy.

Donna Breske (Guest Contributor)

Donna Breske is a licensed Professional Engineer in the State of Washington. She owns Donna Breske & Associates and with her staff provides land use consulting and civil engineering design for numerous infill projects within multiple jurisdictions in the Puget Sound Area. She has a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering from the University of Washington and an MBA from Seattle University. She is married to her husband Fred with whom they share two adult children. She grew up in Seattle and is passionate about eliminating absurd impediments from permitting departments and ensuring consistent and predictable outcomes.