The Sammamish City Council took a small step toward creating a more walkable, active, and vibrant urban core this week, in the face of significant community opposition to increased housing. After a marathon three-and-a-half-hour meeting Tuesday that brought out dozens of commenters, Council voted to advance full analysis of a higher ceiling on the housing capacity in the Town Center compared to the restrictive cap that had been in place for nearly two decades.

The move sets the stage for a major overhaul of land use regulations that have been standing in the way of the city’s own goals for the area. The study could make way for an additional 2,000 homes in the Town Center, assuming Council follows through.

Sammamish is one of the region’s youngest cities, incorporating in 1999 in response to calls to better manage growth on county land between Issaquah and Redmond. Since its early days, creating a Town Center area has always been envisioned as a path toward providing the city with a commercial hub and community gathering space. With a civic campus that’s home to City Hall, a King County library branch, and a YMCA all abutting a large swath of park space, it’s a natural fit for supporting more residents and denser development.

But that density has been slow to develop, a trend that Sammamish city leaders want to turn around with a new plan that’s expected to draw more commercial spaces along with much-needed affordable housing. The hope is that the city can start to grow more sustainably compared to recent decades, when most housing has been built on the city’s periphery.

“Growth is coming. So we can let it happen to us, or we can plan for it,” Sammamish Mayor Karen Howe said ahead of the vote. “We want to expand our very limited choices for housing beyond single-family and have more affordable options. Residents do want amenities, they do want choices — that has been extraordinarily clear, year after year after year.”

Reviving a stale plan

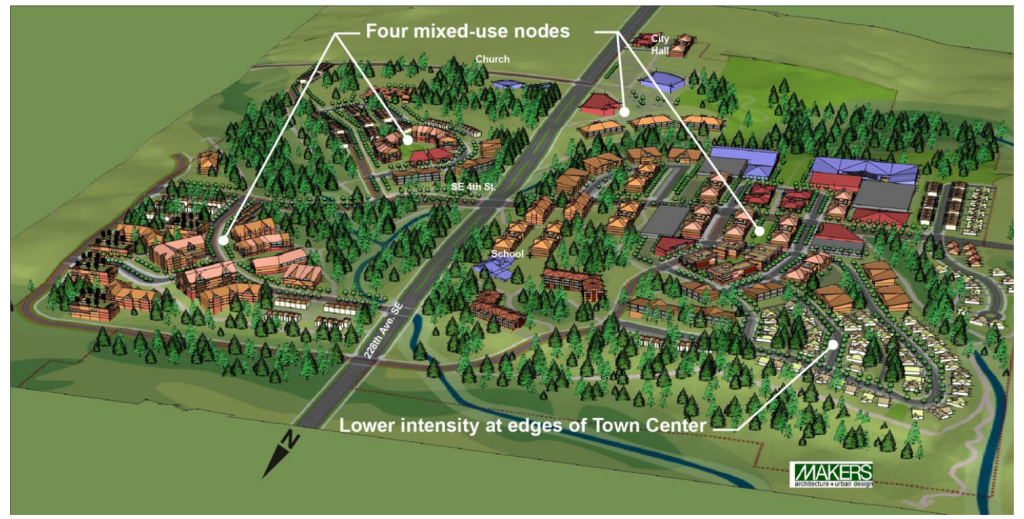

When Sammamish adopted the original Town Center plan in 2008, it spelled out a vision of suburban-style town squares set away from the main corridor of 228th Avenue SE. Brand new roads cut across the landscape connecting lower-scale development, with pedestrian connectivity not prioritized. In the nearly two decades since it was adopted, development hasn’t followed that pattern at all. Instead, projects like The Village at Sammamish Town Center, home to Metropolitan Market, have utilized existing road infrastructure and oriented toward parking instead of the street.

Despite considering the potential of allowing up to 4,000 homes across the entire Town Center, the city council at that time settled on a lower 2,000-unit cap.

“They artificially set it at 2,000 units in the town center. The acreage could support much more than that,” David Pyle, Sammamish’s Community Development Director, told The Urbanist. “They reverse engineered the map to get to 2,000 units, so that there was no more capacity than 2,000 units available in the town center roughly.”

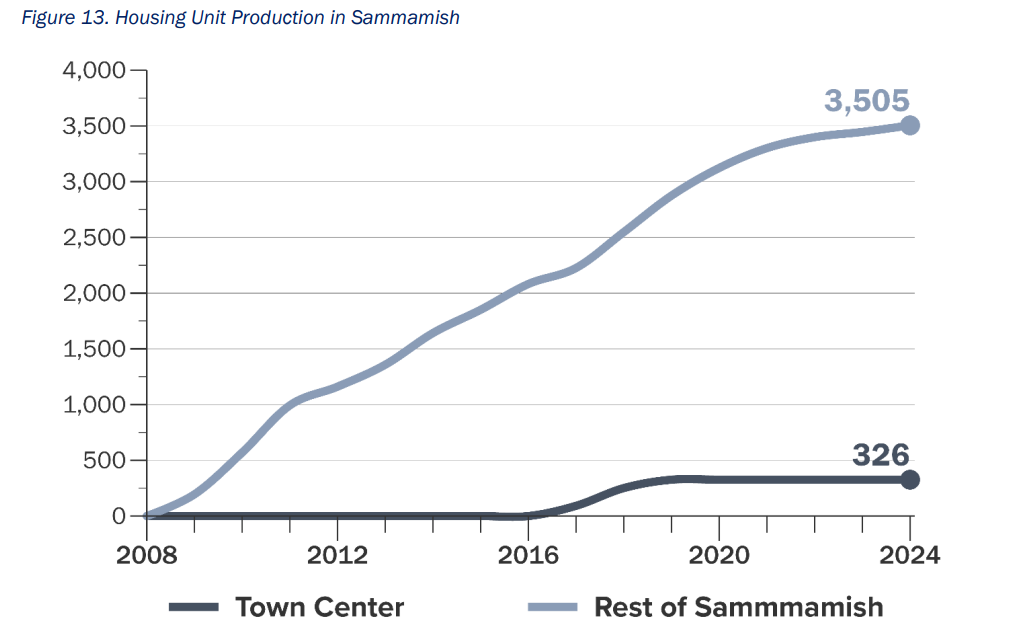

The few mixed-use buildings that have popped up in the area over the past decade-and-a-half have mostly been one-offs, happening not so much because of the plan but in spite of it. Since the Town Center plan was first adopted, Sammamish has added over 3,500 units outside of Town Center — almost all large single-family homes — and just over 300 homes inside the Town Center. At this point, it’s hard to see the plan as anything other than a failure.

“The world has certainly changed quite a bit in 17 years. When you look at the growth that we’ve experienced in the region, when you look at just things that have changed here in Sammamish, the expectation would be that we would have reviewed and adjusted the plan along the way,” Councilmember Pam Stuart told The Urbanist. “There was never really a review done on it.”

Tuesday night’s vote will study bumping up total housing capacity in the Town Center to 4,000, along with implementation of a form-based code that is intended to make development more feasible. Along with shifting the types of housing projects away from townhouses toward larger apartment buildings that can support retail spaces, the update to the Town Center plan is also needed, city leaders say, in order to achieve new state targets for affordable housing. Right now, nearly all of the additional capacity that developers could unlock in Town Center by providing subsidized units has been exhausted.

“We know without a doubt that near zero affordable housing will be built if we don’t make some additional adjustments,” Stuart said.

While the city is clearly aiming to accommodate future residents, councilmembers emphasize the benefits of an improved Town Center that will pay dividends for everyone in the city, including longtime residents.

“If you want to talk about the benefits to the community, well, one is that have large segments, although they tend to be the quiet people of the community who have been dying for us to have more commercial space. We could have restaurants. We could have commercial space for dance studios and music studios and whatever else,” Stuart said. “We have no space for community theater here […] the Sammamish Symphony rarely, if ever, actually performs in Sammamish.”

Planning for transit to come

There’s no doubt that Sammamish, compared to other Eastside cities, is a transit desert. King County Metro’s Route 269 operates on a half-hourly basis between Issaquah and Redmond, stops running at around 7pm, and doesn’t provide weekend service. Routes 216 and 219, both peak-only commuter routes, were suspended by Metro in 2020 and are unlikely to return as the agency shifts to an all-day service model. Despite being within the Sound Transit taxing district, Sammamish only receives five trips a day as a tail off the Route 554, mostly late at night and early in the morning.

Without robust transit access, the issue of increased traffic with future development has been a major sticking point for many Sammamish residents. But city leaders see a denser Town Center as the only way that Sammamish will be able to sustain more robust transit service as the city grows.

“Nobody’s going to give us transit in our current situation,” Stuart said. “We used to have transit. We no longer do. We can, certainly, if we had a town center, figure out a way to partner with Sound Transit or King County Metro or someone, and have a shuttle that runs between the town center and light rail.”

“The idea is with more transit being brought to the Eastside, East Link arriving in Redmond with — out in the future, and hopefully it happens someday — Sound Transit really starting to make headway into Issaquah, that we could start to see some form of more robust connection between transit investments in Redmond and Issaquah,” Pyle said.

Redmond’s light rail connections are not actually very far from Town Center, and with the full buildout of the regional transit network, Sammamish could go from being left out to somewhere that’s well-positioned to be served with frequent transit. The six-mile trip is a 15-minute car ride in light traffic.

“I think that we have to be able to show that we really are going to invest in the region, and then the region will invest in us,” Stuart said.

The misinformation campaign

The weeks leading up to Tuesday’s initial vote have been riling Sammamish politics, with tensions over the future of Town Center running high. The question of what should happen in Town Center is not a new one — in 2022, two councilmembers resigned in the wake of a vote to drop an appeal of litigation related to the area — but the idea of increasing capacity to 4,000 has galvanized opposition.

Save Our Sammamish, a group opposed to the change, created a website that included a laundry list of reasons to oppose the plan, complete with AI-generated images. Along with car-choked roads and skyscrapers, one image showed a burning Sammamish, cars trapped on a roadway in an attempt to evacuate. The website warns of environmental degradation that would come from densifying Town Center, a claim that city leaders clearly rebut.

“Those environmental impacts are really comparing ‘well, what if we didn’t build anything compared to building a town center?’ Yeah, and that’s not an option,” Stuart said, pointing to work that the city has been doing around the future town center to create stormwater infrastructure to reduce harmful runoff.

An online petition circulating among city residents referenced “15+ story buildings.” It has since been altered to only reference “high density housing.” Currently, the tallest buildings in Town Center would be allowed to rise to 85 feet — around eight stories — only with affordable housing included, but no final decisions have been made on building heights.

In the days leading up to the vote, SkyLine high school student Andrew Wong and his two friends created Super Sammamish, a counterpoint to Save our Sammamish that debunked some of that group’s talking points. “Sammamish is boring. Lets change that,” the website’s tagline reads. The group also created their own petition.

“We don’t totally disagree with everything that Save Our Sammamish did or does, but at that time, we were kind of irked the way that they were transcending their message […] On social media, they had some data points that were blatantly incorrect.” Wong told The Urbanist of the decision to set up the site. “We thought it’d be healthy and just good for the community if we provided another voice as for this, where the city is trying to decide on creating a Town Center or not.”

Wong sees the move toward a denser Town Center as one that will help the city become more vibrant and create more third places. And be less boring.

“They’re saying, ‘Oh, don’t let Sammamish just become another Redmond.’ But if you see the way that Redmond is growing and how it’s very fun to be in Redmond, and how there’s a lot of economic vitality there, the same happening to Sammamish is, subjectively, for me, at least a really good thing,” Wong said. “We’re lacking a place in our city — just the ubiquitous place where everyone can just go and hang out.”

Tuesday night’s vote was just an early step, with a full environmental review still to come in advance of any plan’s adoption — and potentially a lengthy appeal. But city leaders see the move as advancing the best interest of Sammamish residents, both current and future.

The sole vote against moving forward came from Councilmember Kent Treen, who offered three separate motions to reduce the number of potential units studied for Town Center. He failed to convince any of his colleagues to deviate from the new preferred alternative at this stage.

“We’re talking about being able to design a plan and infrastructure for a town center that realistically won’t be redesigned for 50 years,” Stuart said. “And if we under plan it, then we’re shortchanging the next generation or the next two generations, and that’s just bad planning.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.