The proposal would funnel data from hundreds more cameras into the Seattle Police Department’s real-time crime center.

The Seattle City Council is considering new legislation that would vastly increase the Seattle Police Department’s (SPD) surveillance capabilities. In addition to adding new surveillance cameras, the proposal would give police access to hundreds of traffic cameras operated by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT).

Last year, the City Council approved a pilot seeking to prevent crime by using a variety of surveillance technologies, including automatic license plate readers, closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras, and real-time crime center (RTCC) software.

Less than three months into the beginning of this two-year pilot, Mayor Bruce Harrell and SPD are already asking for more cameras.

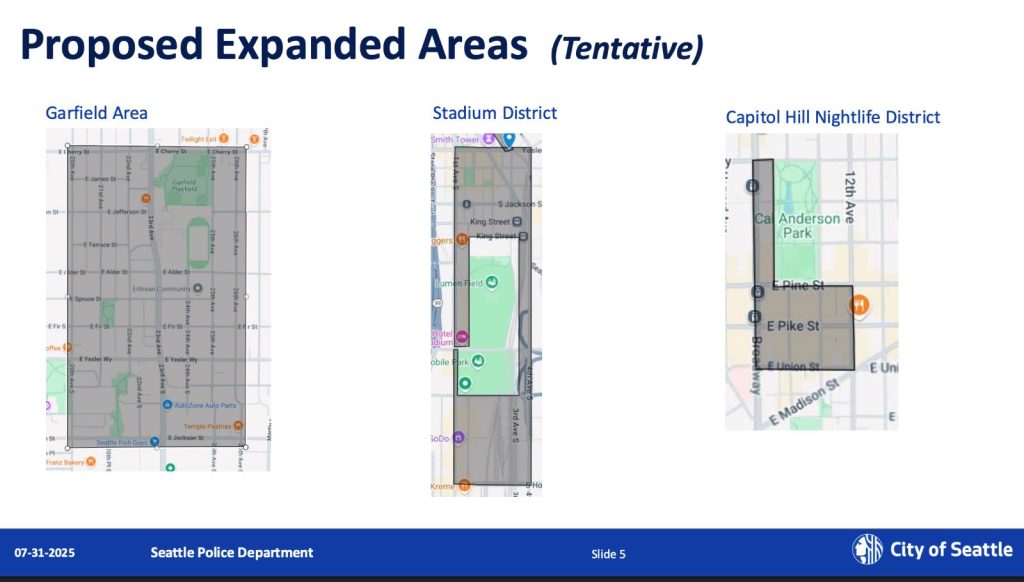

The new legislation would approve CCTV cameras in three new locations: the Stadium District, home of Lumen Field and T-Mobile Park; the Garfield-Nova High School neighborhood; and a section of Capitol Hill that includes the Pike-Pine corridor and Cal Anderson Park.

The new cameras would cost the city $1.025 million for initial purchase and installation, with an ongoing additional annual cost of $95,000. The city is currently facing a budget deficit of at least $150 million for 2026.

Additionally, the legislation would allow SPD to begin viewing and recording SDOT traffic management cameras through its real-time crime center. SDOT told The Urbanist it currently operates 365 traffic cameras, which are spread throughout the city. This number doesn’t include SDOT’s stationary cameras used primarily for traffic counts.

SDOT is able to operate these 365 cameras remotely, adjusting them to monitor traffic conditions and support incident response in real time. SPD did not respond to The Urbanist’s request for information as to whether SPD would be given the ability to adjust the cameras remotely, too.

“Currently, SDOT cameras all broadcast onto a public website, and they’re actually recorded by other parties who sell that footage to insurance companies for their investigative purposes,” SPD Captain James Britt said at last week’s public safety committee meeting.

If the legislation passes, the SDOT camera footage would feed directly into the real-time crime center. SPD would not have access to traffic enforcement cameras, such as red light cameras and school zone cameras.

The City has not yet released an analysis of the camera expansion’s impact on the civil liberties of Seattleites.

Whose Streets? Our Streets! (WSOS), a BIPOC-led workgroup that formed as an offshoot of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, is strongly opposed to the expansion of surveillance in Seattle.

“I’m disappointed that after WSOS’s persistent advocacy with SDOT and the Council to ensure our city’s traffic cameras work equitably for our community’s safety, that these cameras may become even stronger tools to put us in danger,” said Maria Abando, a member of WSOS.

And this could be just the beginning. Britt said he wants to pull footage into the real-time crime center from as many sources as possible.

“We’re reaching out to all city departments that operate cameras to discuss the ability to pull their cameras into the real-time crime center to support our investigative efforts,” Britt said.

Britt said they’re targeting the Parks Department, Seattle Public Libraries, and government partners such as the Port of Seattle and the King County Sheriff’s Office and their partnership with Sound Transit. “We’re discussing basically anybody who has a camera in the Seattle area,” Britt said.

SPD is also working to be able to use private video footage from businesses and individuals who grant them access.

The ACLU of Washington is sounding the alarm about this large new surveillance push.

“The ACLU of Washington is concerned by the proposal to expand CCTV across Seattle,” said Tee Sannon, ACLU-WA’s technology policy program director. “Research shows that the use of CCTV cameras does not reduce violent crime or make our communities safer. Instead, this surveillance technology violates people’s privacy and civil liberties, harms the communities it’s deployed in, and wastes police resources.”

A quick ramp-up of the recent pilot

Seattle began rapidly expanding its surveillance capacity last year as part of Harrell’s Technology Assisted Crime Prevention Pilot. In June of 2024, the council approved an expansion of automatic license plate readers to all vehicles in SPD’s fleet. The readers had previously only been present in 11 SPD vehicles, but now they’re being used in 360 vehicles, not all of which are marked patrol cars.

In October, the council voted to approve two additional surveillance technologies for policing: closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras and real-time crime center (RTCC) software.

This vote came in spite of strenuous objections from the Office of Civil Rights and the city’s Community Surveillance Working Group (CSWG). The CSWG compiled a privacy and civil liberties report that concluded by stating that a majority of the working group was unsupportive of any pilot deployment of these two technologies as described.

One of the concerns of the CSWG, further clarified at the time to The Urbanist by then-co-chair René Peters, was SPD’s potential use of object and clothing recognition technology, which the Community Surveillance Working Group called a “slippery slope” that could lead to further compromising of civil liberties. Britt has since confirmed that while SPD isn’t using facial recognition or biometrics, they are using artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities for object recognition.

Since the pilot program’s approval, 57 cameras have been installed in the 3rd Street corridor downtown, Aurora Avenue in North Seattle, and the Chinatown-International District (CID), with a few more to come. The real-time crime center went live on May 20 and is staffed by two analysts from 8am to 3am each day, seven days a week.

At the committee meeting discussing the expansion, Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck brought up last year’s loud public outcry against increased surveillance.

“Our office, through reading the surveillance impact reports, would also like to note that a majority of the 282 pages of public comments in Appendix E of the RTCC and CCTV demonstrate the existing community perception of these technologies, leading to mistrust over surveillance of communities of color and potential misuse of the data that is being collected,” Rinck said.

The public input period for the proposed expansion was only available online for a short period of time and not broadly advertised.

WSOS has been collecting surveys this summer to find out how Seattleites, and particularly Black people and people of color, feel about surveillance in their communities. Abando told The Urbanist that many people don’t know anything about the various new surveillance technologies. People expressed fear that data would eventually be sold to U.S. Department of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), used to prosecute or intimidate protesters, or contribute to criminalizing poverty.

Abando spoke to a small business owner who was confused that the existing cameras haven’t stopped his truck being broken into on a weekly basis, a woman who felt like the new surveillance equated to modern-day redlining, and a parent concerned about youth being tracked near schools without their consent.

SPD argues for more surveillance

The surveillance pilot was originally presented as a solution to the city’s problems with gun violence, human trafficking, and persistent felony crime. At last week’s meeting, Senior Deputy Mayor Tim Burgess doubled down on this motivation.

“First, we ask the question where should these cameras be installed?” Burgess said. “And there are three criteria that we use to make that determination: the presence of repeated gun violence or the presence of human trafficking or concentrated felony crime that more traditional policing methods has not been able to abate. If a location meets any one of those three criteria, then it potentially becomes a site where we would install the CCTV cameras.”

Studies show that CCTV cameras are most effective for deterring vehicle and property crime but not violent crime, as the Mayor’s Office is claiming is a central aim of the program. The cameras have only been tied to a slight uptick in solving violent crime. A study of Chicago’s real time crime centers shows a 5% increase in clearance rates for violent crimes, compared to a 12% increase in clearance rates for property crimes. There doesn’t appear to be any evidence proving crime centers have a deterrence effect on violence in communities.

During his presentation to council, Britt said that SPD’s new real-time crime center has already assisted in 1,000 emergency calls and more than 90 violent crime investigations, which suggests its usage has been as a reactive measure as opposed to a preventative one.

Britt presented a video with three examples of cases in which the real-time crime center had been helpful. The first case involved a car chase in which a person was chasing after their stolen vehicle and allegedly shooting at it. The person SPD took into custody was the driver who allegedly stole the car and was being shot at, while the shooter had their stolen car returned. The second case involved a man walking around with a knife who wasn’t prosecuted because other people at the scene were unwilling to cooperate. The third case involved a car hitting a pedestrian, and the case is still ongoing.

None of these cases seem to illustrate gun violence, human trafficking, or concentrated felony crime, and the only person to fire a gun appears to have been rewarded for that behavior.

Peters no longer serves on the CSWG but is deeply familiar with the original pilot proposal.

“The base metric that the City and Seattle PD built the proposals on was reduction in felony crime. I have only seen talk of the number of investigations data is being used in — that is extremely obscure as the results of the investigations may be still in the air,” Peters said. “We underlined multiple times that on top of the fact that other cities have reported that programs like this don’t address the core metric, it would take time to collect the data. The recent moves indicate that there was never any honest intent to base expansions off of observed improvement.”

Surveillance net widens across the U.S.

Public safety chair Bob Kettle encouraged the public to raise questions but to do so in a Seattle context.

“Making an argument against a program using a–for lack of a better phrasing–Red State America jurisdiction that doesn’t care, that will be opting in, as Captain Britt noted, that’s not really helpful, because their laws are so different, their legislation, their policies are so it’s not comparable,” Kettle said.

Seattle does exist within the national context, however, which includes the recent federal budget reconciliation package. In addition to making huge cuts to Medicaid and SNAP, this legislation makes a historic jump in ICE funding, which is already being used to expand surveillance systems. ICE has a contract with Palantir to build a surveillance platform called “ImmigrationOS.”

In addition, ICE is pulling together massive amounts of data. The agency is searching a massive insurance and medical bill database called ISO Claimsearch, and it will be able to obtain home addresses through a system the IRS is building to share taxpayer data. ICE is using AI to scrape social media for data, and a data broker is selling domestic flight information to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. ICE has also recently launched a sweeping expansion to their electronic monitoring program.

Blue states are not immune from invasive surveillance, even when governed by various shield and privacy laws. License plate reader data from Illinois has been shared with ICE even though Illinois has a robust shield law. California has legislation in place that makes sharing license plate reader data outside the state explicitly illegal, and yet law enforcement agencies in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, San Diego County, Orange County, and Riverside County have shared this data with ICE and federal law enforcement on numerous occasions.

Here in Washington State, King5 discovered that the Department of Licensing is giving ICE and other Homeland Security departments access to drivers license and vehicle information, violating state law. The Urbanist reported that license plate reader data has been shared across the country by the King County Housing Authority, with an audit suggesting this data has been used to assist ICE.

Meanwhile, Washington State is suing to stop its food stamp payment processor from sharing participant data with the federal government, as well as suing the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for allowing the Department of Homeland Security, including ICE, to access personal Medicaid data.

Peters expressed concern that a recent executive order from Trump about “preventing woke AI in the federal government” could encourage a lack of transparency and community engagement in Seattle’s efforts to ramp up surveillance.

“Now that the federal government has put into writing that it will ignore things like unconscious bias and intersectionality when it comes to AI, Seattle’s mayor, city council, and SPD will feel no urgency to provide more clarity behind the rollout. On the contrary, they may take a tacit cue to accelerate,” Peters said.

Inconvenient as it may be for proponents of the program, Seattle is considering a major expansion of its surveillance apparatus in a country where people are being deported without due process and personal data is being collected at an unprecedented scale and compelled into federal hands for that very purpose.

Next steps for the expansion

At the committee meeting, Rinck specifically asked what would happen if a whistleblower discovered ICE or Red states were using SPD surveillance data.

“If we found out that there had been some unwarranted or unacceptable intrusion into our data, we would escalate it immediately to the Executive and certainly would lead with recommending either remedying whatever led to that breach or shutting down the program if we find out we actually cannot control it,” said SPD Chief Operating Officer Brian Maxey.

The surveillance expansion will likely receive a committee vote on August 12, followed by a full council vote sometime in early September.

The two-year pilot is set to be evaluated for efficacy by Principal Investigator Anthony Braga and Co-Principal Investigator Lisa Barao at the University of Pennsylvania’s Crime and Justice Policy Lab. A $300,000 contract for their services has not yet been signed.

The team is supposed to deliver the first of two reports sometime next summer, according to Burgess. It is unclear whether this evaluation will also include an analysis of the social costs of increased surveillance.

“Overall, I am deeply concerned the City isn’t educating people about the details of this surveillance or listening to people who insist that these technologies don’t make them feel more safe,” Abando said.

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.