The Mayor’s move to roll out gunshot detectors, closed circuit cameras, and expanded real-time crime center software has raised privacy and equity concerns.

Whether in George Orwell’s classic 1984 or newer portrayals of ubiquitous monitoring in television shows like Silo and Person of Interest, our society has been grappling with the tension between surveillance, privacy, and civil rights for several decades. We know that the new push towards surveillance-driven policing targets communities of color and other marginalized people on a large scale. And now, here in Seattle, we find ourselves right at the center of this debate.

Seattle IT recently announced the next step in the approval process for three pieces of surveillance technology Mayor Harrell wishes to gift the Seattle Police Department (SPD) as part of their new Technology Assisted Crime Prevention Pilot: a closed-circuit television system (CCTV), an acoustic gunshot location system (AGLS), and integration with real-time crime center (RTCC) software. Together this technology package would represent a remarkable increase in everyday surveillance in the city of Seattle.

The draft “Surveillance Impact Reports” for these three technologies (required by the City’s surveillance ordinance) cite “unprecedented staffing shortages” as the motivation behind their adoption, as well as a desire to increase responsiveness to crime victims and raise case clearance rates, which are admittedly abysmal: SPD only cleared 24% of homicide cases in 2021, for example.

Possible deployment locations include Aurora Avenue North, Belltown, the Chinatown-International District, and the Downtown Commercial Core, according to the report.

Let’s break down the effectiveness of each of these three technologies along with potential harm and civil liberties issues.

Acoustic Gunshot Location System

AGLS technology typically consists of arrays of microphones deployed across certain neighborhoods of a city. Its sensors send audio files to human analysts who try to determine whether the sound is a gunshot, along with the location of the sound.

The most common AGLS technology is called ShotSpotter, sold by publicly traded company SoundThinking, and deployed in more than 150 American cities, as well as overseas in places like South Africa and Uruguay. SoundThinking partnered with Airobotics to provide gunshot detection services in Israel and Palestine back in 2021.

Seattle’s impact report for AGLS states the technology will locate victims of gun violence more quickly and increase justice for victims. Evidence is mixed on whether this is actually the case, with two studies showing no impact of the technology on mortality rates.

Meanwhile, a new review by the Cook County state’s attorney’s office found that ShotSpotter has a “minimal effect on prosecuting gun violence cases.” The report states that “ShotSpotter is not making a significant impact on shooting incidents,” with only 1% of shooting incidents ending in a ShotSpotter arrest. And it estimates the cost per ShotSpotter incident arrestee is $217,368.42.

A large 2021 study found AGLS has no impact on the number of murder arrests or weapons arrests. And Chicago’s Office of Inspector General concluded from its analysis that “CPD responses to ShotSpotter alerts rarely produce documented evidence of a gun-related crime, investigatory stop, or recovery of a firearm.” There are similar reports from Atlanta, Pasadena, San Antonio, and Dayton, Ohio.

The City’s report goes on to say: “While the current literature on AGLS does not support its efficacy as a means to improve the speed and quality of police response, nor a means of enhanced reporting, no research to date has addressed the application of AGLS in the context in which SPD intends to deploy it as a component of a broader forensic tool to support criminal investigations. For that reason, the existing research on ALGS [sic] alone is not helpful.”

This ignores that many cities using AGLS have already combined it with CCTV and real-time crime center technologies. For example, Chicago has deployed AGLS in concert with CCTV cameras and RTCCs called strategic decision support centers, and therefore studies about AGLS from Chicago shouldn’t be discounted. Similar combinations can be found in Cleveland, Oakland, and Flint, Michigan. While this combination of technologies should doubtless be studied further, the fact that it is currently understudied is not a particularly compelling argument to move full force ahead, given the concerning individual study results for each separate technology and the fact that this isn’t a combination that is proven to work.

Jonathan Manes, a lawyer involved in the MacArthur Justice Center’s study on ShotSpotter, had this to say: “In multiple studies, ShotSpotter has been found not to reduce gun violence, even when used in conjunction with other surveillance technologies like surveillance cameras.”

“ShotSpotter also does not make police more efficient or relieve staffing shortages,” Manes continued. “It’s actually the opposite: ShotSpotter vastly increases the number of police deployments in response to supposed gunfire, but with no corresponding increase in gun violence arrests or other interventions. In fact, ShotSpotter imposes such a massive drain on police resources that it slows down police response to actual 9-1-1 emergencies reported by members of the public. This has real world consequences.”

While you probably don’t need to worry about AGLS microphones listening in on your private conversations, its high false positive rate leads to false arrests and more contact between police and community members. Chicago found its use led to an increase in pat downs, searches, and enforcement actions, and the MacArthur Justice Center has brought a class-action lawsuit against Chicago to “end the unconstitutional and discriminatory use of ShotSpotter, and to end unconstitutional ShotSpotter stop-and-frisks.”

Just this week, in response to these studies, Chicago’s Mayor Brandon Johnson announced the city will not be renewing ShotSpotter’s contract this year. He said, “Moving forward, the City of Chicago will deploy its resources on the most effective strategies and tactics proven to accelerate the current downward trend in violent crime.”

In spite of Seattle’s 12-year consent decree, SPD still detains and frisks Black and Indigenous people at much higher rates than White people, even though White people are more likely to be found with a weapon when frisked. How much worse might this bias become if exacerbated by technology?

CCTV

CCTV technology, or closed circuit TV, is a TV system involving cameras in which the signals are monitored for security and surveillance purposes. The most CCTV cameras are deployed in China, followed by the United States, Germany, and the U.K. Nine of the top ten most surveilled cities in the world are also located in China, the only outlier being London.

The impact report for CCTV states that the City believes the technology will both deter crime and assist at collecting evidence at specific places. Again, evidence on this is mixed, and how this technology performs at assisting in collecting evidence is understudied, in spite of the widespread deployment of CCTV cameras throughout the world. The only study cited in the City’s report, a 40-year systemic review, finds CCTV is most effective for deterring vehicle and property crime, not the “gun violence, human trafficking, and persistent felony crime” referenced as the motivation for obtaining this tech.

Unfortunately, CCTV has been found to be vulnerable to discriminatory targeting, meaning that Black people are more likely to be surveilled. The cameras are also ripe for abuse, with operators using the received footage for blackmail and selectively spying on people. Police departments have also been documented both altering and losing key footage that might show police misconduct.

Meanwhile, there are concerns that living in the real-life panopticon created by CCTV could change the essential character of public life. We are already seeing how the removal of many third places impacts people’s social lives and levels of loneliness. Knowing they are being surveilled changes people’s behavior in ways that have nothing to do with committing crime, including discouraging them from practicing their rights to speech and peaceful protest. People who stand out are more likely to be surveilled for a prolonged time, and this includes people who are distinctive because of how they dress, how they speak, or even what they’re reading.

Real-time crime center software

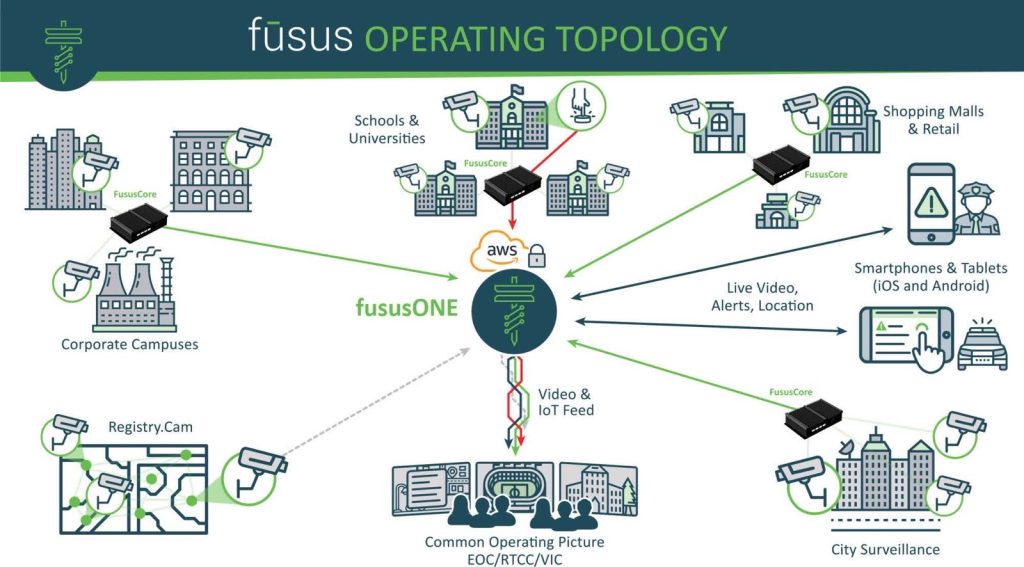

RTCC software, sold by companies such as Fusus (recently acquired by Axon), Genetec, and Microsoft, generally involves a cloud-based software platform designed for real-time crime centers to integrate multiple surveillance technologies such as cameras, automated license plate readers, and gunshot detection technology. Some of this software uses non-generative AI for purposes like object detection. It results in a single view for the police department showing all the available data.

SPD has had RTCC software since 2015, before the surveillance ordinance passed in 2017. But now that SPD wants a new system categorized as surveillance technology, it must go through the City’s surveillance impact report process.

Seattle’s impact report for RTCC software says it will increase case clearance rates and decrease crime rates, as well as provide situational awareness to allow for quicker dispatch and the reduction of unnecessary stops. Again, academic research on the impact of real-time crime centers is limited and shows modest improvement in case clearance rates at best. A paper cited in the report found these centers increased case clearance rates for violent crimes by only 5%.

These platforms can build a vast network of cameras, notably including cameras privately owned by individuals and businesses and collect a massive amount of data. This leads to them being privy to sensitive personal information such as where a person lives and works, their religious affiliation, who their friends are, what medical care they are seeking, and more.

This technology poses a particular danger to criminalizing vulnerable populations such as undocumented people, sex workers, trans people, and people seeking abortions. Once the data is collected by these systems, it is difficult to ensure it won’t be used in harmful ways or shared with other law enforcement agencies, including ICE. Even though Seattle has an ordinance that requires all requests from ICE be referred to the Mayor’s Office Legal Counsel, this isn’t sufficient to protect against data exchange. Officers may share data in spite of the policies in place, or the data might pass through several other agencies, including those out-of-state, before ultimately reaching ICE.

A data privacy problem already exists in Seattle due to the recent “dramatic expansion of vehicle surveillance” last fall, when council members approved the purchase of many more license plate readers. Preventing this data from being shared once collected is very difficult, if not impossible. RTCC software has the potential to exponentially worsen this problem due to the large amounts of data it collates.

The integration of privately owned cameras into this mix of data also presents new difficulties. This potentially vast expansion of Seattle’s surveillance camera network can happen without meaningful oversight or input from residents. The privately-owned cameras also complicate laws and restrictions that normally limit police, including being able to potentially bypass the process of getting a warrant to view footage, using this ability to “spy on protestors and perpetuate the long history of over-policing of activists and communities of color.”

Even if there were policies in place preventing the City’s cameras from filming certain sensitive places (such as Planned Parenthood), there would be nothing to stop someone from pointing their own privately owned camera where they liked, the data of which would then still be integrated into the RTCC software. While a scenario like this would likely prompt legal action, the harm would already be done.

If the city were to purchase Fusus, which is the most common software of this type and much cheaper than Genetec, the software might violate Seattle’s surveillance ordinance by its very nature. It uses image recognition algorithms on all incoming video, and the company claims it is constantly adding new algorithms, meaning a continuous introduction of new and unvetted surveillance tools. One of the issues with these algorithms can be the racial bias baked into them by the data sets on which they were trained.

Where we are in the approval process

While $1.5 million has already been allocated in the 2025 budget to pay for these technologies, they first need to go through the Surveillance Impact Report process. The initial drafts of these reports were publicly released at the beginning of the month. Public meetings are required to solicit feedback.

The City is holding two public meetings during its 25-day public comment period. One was on Monday, February 12 at 12pm, and the second is upcoming on Tuesday, February 27 at 7pm at Bitter Lake Community Center, with a virtual option. Public input is also being solicited via survey forms for each of the three technologies that can be filled out online.

To put this timeline into perspective, when the Dayton, Ohio police department was going through their surveillance technology oversight process to obtain only one of these technologies – RTCC software – they held a total of 13 public sessions before participation in the pilot came to a vote. This is in a city with 17% the population of Seattle.

At the first public meeting on February 12, commenter after commenter opposed adoption of the new technologies and called for the process to be slowed down to allow for more community engagement and outreach.

Dr. Tee Sannon, the technology policy program director at the ACLU of Washington, agreed with the case community members made in public comment.

“It is disappointing that the city is trying to rush ineffective and dangerous gunshot detection technology to Seattle’s streets, along with closed-circuit tv and real-time crime center technologies that have the potential to violate privacy and undermine civil liberties,” Sannon told The Urbanist. “Such extensive surveillance systems chill free speech, deter free association, fuel racial disparity in policing, and provide a false sense of security at the cost of privacy and race equity.”

“Given these risks, it is crucial that communities that are disproportionately impacted by these technologies have their voices and concerns heard,” Sannon continued. “We are deeply concerned that the city has provided less than a month and only two hearings for public comment. We call on the city to slow down and meaningfully engage the public in the surveillance ordinance’s mandated review process.”

City ordinance also requires a Racial Equity Toolkit (RET) to be completed for each technology. In this case, the RET is supposed to be conducted jointly by the Mayor’s Office, the Office of Civil Rights, and the Office of the Inspector General. This process involves analyzing existing data and studies and getting feedback from communities and stakeholders.

Unfortunately, RETs can become a perfunctory step, a box to be checked rather than a robust process that meaningfully evaluates – or prevents – harms and racial disparities. These RETs also cannot be performed properly until the final locations for the deployment of the AGLS and CCTV equipment have been selected, again suggesting this process is being rushed.

Next in this process, the CIty will issue a final draft of the impact report for each technology, incorporating the public feedback received. The surveillance advisory working group then reviews each report and completes a civil liberties and privacy assessment. This working group currently appears to have only one active member, so there is an open question as to how it will even be able to achieve a quorum to complete such an assessment.

In the last step of the process, the completed surveillance impact reports are sent to the City Council for a final vote.

This is a policy decision, not an inevitability

Gun violence is an issue of grave importance in our community: there were 69 homicides in Seattle in 2023 alone, many of the deaths due to gunshot wounds.

Unfortunately, this policy decision has been defined as one between vastly increasing surveillance in Seattle and doing nothing. This is a false choice.

These three technologies have not been shown to prevent gun violence before it happens, nor have they been shown to be particularly effective at increasing convictions. “It would be wonderful if technology could somehow solve our gun violence problems, but this technology hasn’t yielded the results,” said Jonathan Manes.

In contrast, gun violence prevention programs have shown notable reductions in gun violence over time. Hosting gun buyback events and giving out free firearm lockboxes to store guns more securely also help, as does purposeful environmental design: turning vacant lots into parks and gardens, creative placemaking, improving lighting, and planting trees. Guaranteed basic income programs have also been shown to reduce firearm violence and address inequality, which predicts homicide rates better than any other variable.

We know these surveillance technologies can undermine and violate important civil rights while also encouraging racial disparity and misconduct in policing, and they haven’t been shown to meaningfully reduce violence. Seattle could invest in programs that lower gun violence in our community without dramatically expanding police surveillance.

Whatever policy choice the Harrell administration ultimately makes, impacted communities and concerned residents deserve to have their input heard and considered before any drastic steps are taken. Rushing through the process mandated for new surveillance technologies isn’t a good look for anyone, let alone a Mayor who ran on a promise of equity for all.

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.