The city of Mercer Island fell well short of state affordable housing requirements when it adopted its last major growth plan update, the state’s Growth Management Hearings Board ruled late last week. The ruling came in response to an appeal by the land use advocacy organization Futurewise, along with two Mercer Island residents, asserting the city didn’t do enough to respond to new state laws requiring local governments to plan for future housing needs across a broad range of income levels.

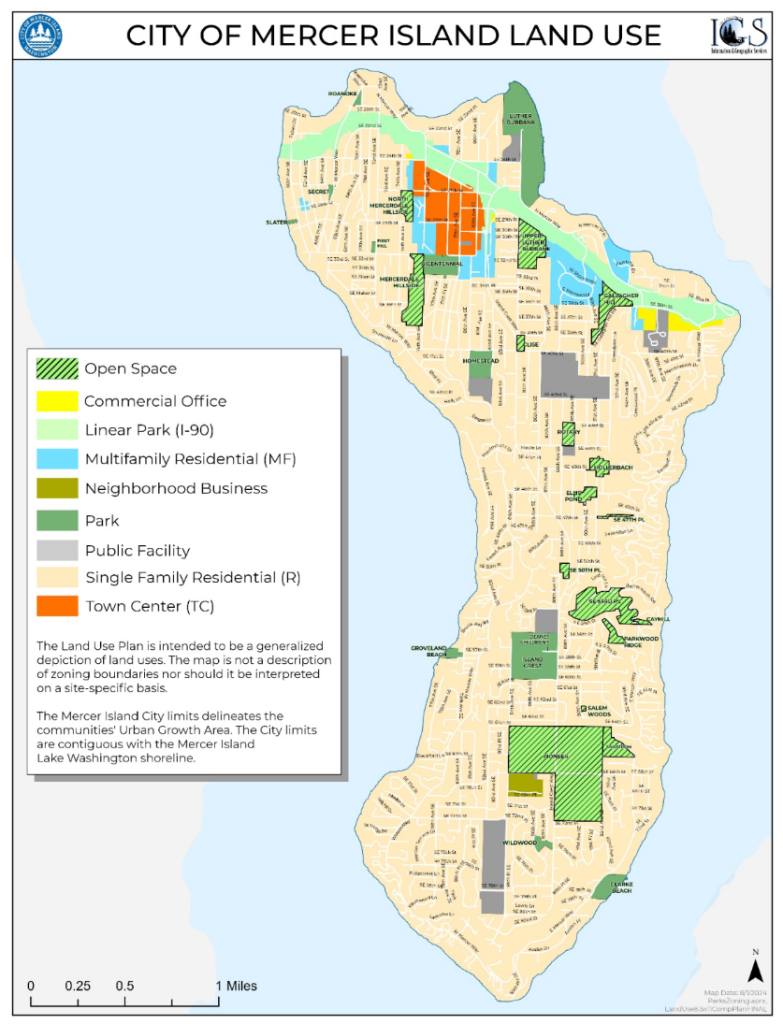

Mercer Island will now have to head back to the drawing board, after its city council spent much of 2024 trying to craft a plan that it thought met the bare minimum state standard. The changes adopted in December left zoning across most of the city mostly unchanged, even as Sound Transit plans to open a light rail station within the city in 2026.

“In a statewide housing crisis, everyone needs to their part. This ruling will ensure that more people, particularly lower-income people, will have access to the great amenities and opportunities that Mercer Island has to offer,” Futurewise Executive Director Alex Brennan told The Urbanist in response to the decision.

Futurewise’s appeal represented a crucial legal test that will likely have profound implications well outside of Mercer Island’s borders. This is the first time the state Growth Management Hearings Board (GMHB) has fully grappled with a challenge to a local Comprehensive Plan under 2021’s House Bill 1220, which requires cities and counties to plan for future housing needs across a range of incomes specific to each jurisdiction. And the final ruling affirmed the state’s 2021 reform as representing a sea change in growth planning, referring to a new, post-HB 1220 “world.”

Where previously a city like Mercer Island only needed to accommodate one high-level 20-year housing growth target, ensuring that it has enough zoned capacity to accommodate that expected level of growth, under HB 1220 the requirement is to go further and specifically plan for households of different incomes.

In Mercer Island, for example, that means making room for 339 households making 30% of King County’s area median income (AMI) or lower — around $36,000 for a family of two, along with hundreds of other households with income levels higher than that, but well below Mercer Island’s median.

The GMHB found that Mercer Island had lumped the vast majority of its future housing target together, treating all future households with an expected income of 120% of the county’s AMI — incomes that can be well above $120,000 — the same. Virtually all of those new households were assumed to be accommodated in Mercer Island’s Town Center, a compact area to the south of I-90 close to the city’s forthcoming 2 Line light rail station, with only a few additional feet of height limits on certain blocks.

Combining those income levels together conveniently allowed Mercer Island to hide the fact that most of the housing for very low income households almost certainly wouldn’t materialize in the Town Center. The average single family home price in Mercer Island is just shy of $2.4 million, according to Zillow, making it one of the wealthiest cities in the state.

“Aggregation concealed the reality that most of the land capacity the City identified as available to all low to moderate income segments will only be available for the moderate income segment at best,” the ruling noted. “The City would need a greatly expanded program of subsidies and incentives to provide sufficient inventory for the low, very low, and extremely low income segments, and no such program is identified or proposed in either of the challenged ordinances.”

When deciding to upzone a small portion of the Town Center area, the Mercer Island council also voted to ratchet up affordability requirements there, mandating that housing projects over two stories set aside 15% of new units for households making up to 50% of King County’s median income. But the GMHB noted that Mercer Island assumed that essentially every single unit within the Town Center area would be available to lower-income residents while knowing that this clearly couldn’t be the case.

“The fact that only 102 rent-restricted units have been produced under the City’s current system of subsidies and incentives should have led the City to question the assumption that all or nearly all of the 1,073 units for which the City still has capacity will turn out to be a rent-restricted unit,” the board noted. “Nothing in the record supports such an assumption.”

Futurewise also asserted that Mercer Island has an obligation to avoid concentrating lower-income housing in one specific area of the city, in this case next to the city’s interstate highway. But the board didn’t agree, despite language in King County’s 2021 Countywide Planning Policies (CPPs) that directs cities to work to increase “access to affordable housing to rent and own throughout the jurisdiction.”

Instead, they ruled that state law or county policy includes “no prohibition against concentrating affordable housing in the zones where it is most feasible to provide,” a precedent that could reinforce current practice of zoning the least desirable areas of a city as locations where low-income housing will most likely be built.

But taken as a whole, the ruling represents nothing less than a klaxon call for cities across the region that have likely been making the same sorts of assumptions around future housing growth as Mercer Island.

Now, Mercer Island will have one year to consider more substantial zoning changes that align with more reasonable expectations about where future low-income Mercer Island residents will live — and grapple with its relatively meager slate of existing programs intended to produce affordable housing. The city contributes $35,000 annually to the A Regional Coalition for Housing (ARCH) trust fund, an amount that translates to $1.35 per Mercer Island resident — an amount that is just 0.3% of a Seattle resident’s share of the 2025 budget for the city’s Office of Housing.

“Correcting the errors identified in this decision may require the City to redo housing studies that took months. Even more dauntingly, the City may then have to make challenging decisions to accommodate the more than one thousand low to moderate income households the City has been allocated,” the GMHB ruling states.

In explaining its rationale for granting a year to get into compliance, the board ultimately highlighted the reasoning that the change in state law is so significant — it has the potential to spur action in cities that haven’t been front-and-center when it comes to encouraging the production of affordable housing, even as nearly every jurisdiction across the state would likely cite it as a top priority. But leaving that work to big cities is no longer on the option block.

“[T]he City’s failure to establish capacity and make adequate provisions for low to moderate income households is a serious matter, directly affecting low income households within the city and indirectly affecting households and jurisdictions across the entire multi-county region,” the board noted.

Futurewise is currently in negotiations over an appeal with the City of Clyde Hill, the exclusive enclave of 3,000 people wedged between Medina and Bellevue, with many of these same issues at play there. Depending on how exactly Mercer Island’s attempts to come into compliance play out, the implications of this ruling could ripple across the entire state.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.