A debate over a planned affordable housing project on Bainbridge Island turned from a simmer to a boil this month. A new campaign titled “Save the Corner” seeks to derail the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) from moving forward with plans to build 92 subsidized units on a parcel of city-owned land near the state ferry terminal. Despite an island-wide need for more affordable housing, a group of Bainbridge Island residents contend that the prime site across the street from the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art is too valuable to use for that purpose.

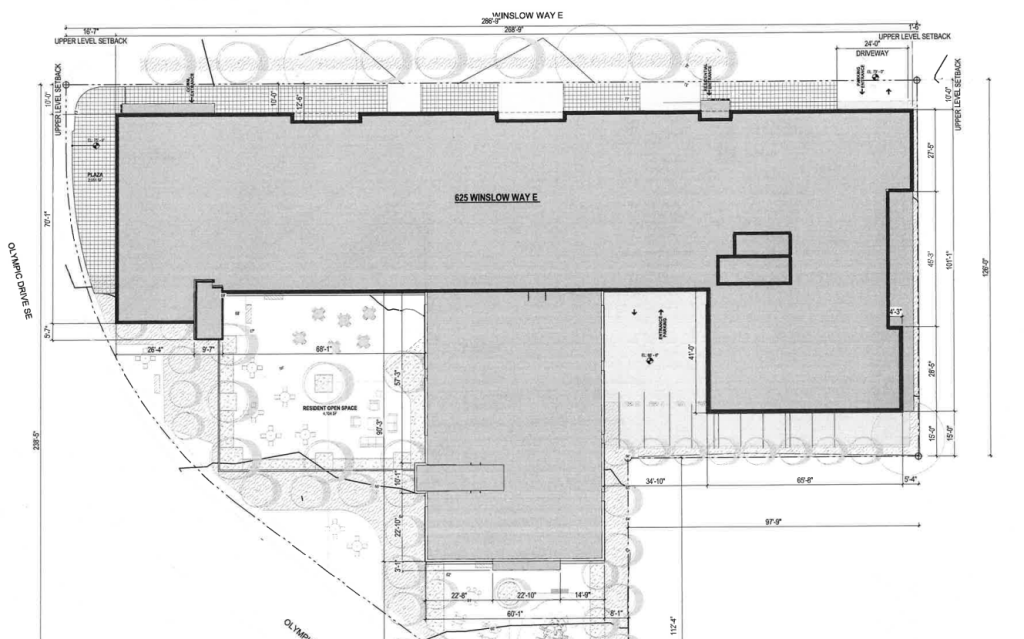

The City of Bainbridge Island has been working toward getting shovels in the ground on an affordable housing project in Winslow since 2022, when it identified the property at 625 Winslow Way, a vacant lot that formerly hosted the city police station. This May, the Bainbridge City Council unanimously approved a development agreement with LIHI, which is proposing to build a mix of 38 one-bedroom units, 13 two-bedroom units, 18 three-bedroom units, 19 studio units, and four live-work units.

“We must not rush into a decision that will shape the front door to our island for generations. The Corner at 625 Winslow Way belongs to the public, and its fate should be determined with care, transparency, and the broadest possible community input,” reads the Save the Corner website, created by Bainbridge resident and architect Matthew Coates. “Affordable housing is essential. But it can be met through distributed, thoughtful solutions: ADUs, smaller-scale mixed-use projects, and redevelopment across the city, rather than concentrating it all in one place.”

Opposition to the LIHI project has ramped up following the release of conceptual renderings shown at a public meeting in late May, with concerns raised around the building’s height, its overall design, and the amount of parking proposed. LIHI’s design includes one structured parking stall for every two units in the building, along with around a dozen stalls for visitors and for carshares. That’s a reduction compared to what Bainbridge Island would normally require — one stall for every single unit. LIHI said the reduced parking would save around $2 million in building costs.

Coates, who started Save the Corner, told The Urbanist he wants to see the project happen, just not at this prominent intersection where Bainbridge Island ferry traffic meets the city’s main street.

“My agenda has never, ever, ever been, and never will be, to stop the project. It’s to not build on that particular piece of land because it’s too important to our community,” Coates said. “It’s the first thing you see when you arrive, and it’s the last thing that you see when you leave. And it’s, for many reasons, more important to the greater good than it is to 90 people.”

In addition to finding a new site for LIHI’s project, Coates wants the city to return to the drawing board when it comes to the future of the 625 Winslow property. The Save the Corner site suggests some potential uses for the land, including an island visitor’s center, a public plaza and park, or a cultural center.

“What should have been done, in my humble opinion, is the city should have opened up a conversation with the community at the very beginning and said, ‘What should we do on this property? What would you like to see here?” Coates said. “This is your property. It is very valuable. It is very meaningful to this community. What would you like to see here? And if the answer is a 90-unit low-income housing project, so be it. But that conversation never happened.”

Despite the unanimous council vote in May, the project is once again facing a need for city council approval. As designed now, LIHI’s plans go beyond the existing zoning and development standards for the site. Bainbridge Island’s pending Comprehensive Plan update and adjoining Winslow subarea plan are poised to set new parameters specifically for affordable housing projects, but that work is months behind schedule. So the Bainbridge Island Council has asked the city’s planning commission — which has so far held 19 separate meetings deliberating on the specifics of the new plan for Winslow — to expedite recommendations that can be approved by this fall, ahead of when LIHI plans to submit its first major permit.

Last week, the planning commission was expected to schedule a public hearing for an ordinance that would allow the project to advance ahead of the Comprehensive Plan update — and also permit any other 100% affordable building within in Winslow’s “core” or the ferry district.

But in a 3-1 vote, commissioners voted against doing so, citing many of the same issues that have been raised by project opponents, along with a reluctance to give this project special preference even if it’s far along in the process. That’s in spite of the fact that the commission had already created preliminary recommendations for new standards in the ferry district that would have permitted this project — and potentially an even larger building on the site.

Sarah Blossom, the planning commission’s chair and a candidate for an open seat on the city council in District 3, put the amount of planned parking at the top of her list of concerns. Blossom’s opponent in November, Mike Nelson, is campaigning on a platform of “keep[ing] Bainbridge Bainbridge” and opposes the plan to increase density in Winslow to pave the way for more affordable housing.

“Even if you’re near a ferry, have access to good transit — which we don’t — you still need a car. You need to get to the [Kitsap] peninsula,” Blossom said at Thursday’s meeting. “The idea that half the residents, half the units in this building, won’t have access to a car because they’re low income. I mean, when I hear from half of this island willing to give up their car, you know, maybe I’d consider it, but to me, a car is freedom.”

Coates, who has helped design other affordable housing projects elsewhere in Kitsap County, contends that the unique constraints on the site, especially when it comes to parking, make it a poor choice for housing.

“It just makes no financial sense at all to put underground parking on that site,” Coates said. “I have over 30 years of experience doing this. So, my opinion does matter more than some keyboard person who has an opinion about it. I’ve been doing these kinds of projects for a long time, and I speak with some authority on the matter about these costs, and I’m telling you, I would much rather see this project get built any other place downtown, that where the parking is not artificially weighing the construction cost down so they could actually afford to build a decent project.”

Alex Preudhomme, the only planning commissioner to recommend moving ahead with consideration of an ordinance, painted concerns around the process as overblown. “This is just a project that happened to be ahead of the curve,” Preudhomme said Thursday. “[We’re] trying to figure out how to get one of our only city-owned parcels to deliver. You know, we have very few tools that we can use to achieve affordability.”

Bainbridge Island is going to need to figure out how to deliver affordable units at a scale that it previously hasn’t had to grapple with. Out of the 1,977 housing units that Kitsap County is asking Bainbridge Island to plan for through 2044, around half will need to be available to households making less than 80% of the county median income — approximately $77,000 per year for a family of two. With other high cost cities like Mercer Island grappling with the impact of new mandates like these, a bespoke process like the one happening here for every single project on the island clearly won’t work to actually create those units.

While the planning commission’s recommendations will carry weight, it will ultimately be up to the council to decide whether the project could move forward at its current pace. At a meeting in July, councilmembers also raised concerns about parking, and the building’s design, suggesting there should be additional “step backs” above the first floor to reduce its scale. Upper-level step backs generally add building costs, with Bainbridge Island only contributing $3 million in direct funding to LIHI in addition to providing the land for a long-term ground lease. The total cost for the building is expected to be around $50 million.

“I will not be able to vote for something that is not stepped back from Winslow Way, period,” Councilmember Kirsten Hytopoulos said.

Hytopoulos suggested that the city look at reducing the number of two and three-bedroom units, which would reduce the size of the building. Two and three bedroom affordable units are typically highly coveted by local governments who are seeking to provide housing options for families. Hytopoulos also raised concerns that incomes of the new residents moving into LIHI’s building could be too low, despite a regional need for more deeply affordable housing.

With this project representing Bainbridge Island’s first major foray into subsidized housing, it’s clear that the city’s leaders are running into a conflict between Bainbridge’s perception of itself and the need to make big moves to ensure that the city maintains income diversity — and that the island’s workers can afford to actually live within city limits. Between 2000 and 2020, the share of family households with children on Bainbridge declined from 49% to 35%, as the average age of island residents increased from 43 to 50 years old.

“This is a small town, 25,000 people — we’re not Seattle,” Councilmember Joe Deets said, joining the chorus asking for step backs. “And so a Seattle design may not be — I don’t think [that] would work too well for us.”

Within the coming weeks, the council will have to decide whether to keep the project on track, or whether to punt it further down the road. And for now, there are voices in favor of pushing ahead.

“Every time affordable housing comes up on this dais, there is always someone who says, ‘I would vote for this, but…’ And then they name 100 reasons, and they all sound plausible,” Councilmember Brenda Fantroy-Johnson said. “When the bottom line is, do we want to do this or not?”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.