It’s been only a few weeks since Washington’s Growth Management Hearings Board issued a decision that deemed Mercer Island’s newly adopted Comprehensive Plan out of compliance with a new state law directing local governments to plan for affordable housing. Even so, the repercussions of that decision are already starting to be felt around the region, rippling across other cities struggling to come to grips with the same mandates.

The August 1 ruling was the first major challenge to a local Comprehensive Plan under 2021’s House Bill 1220. The state’s new law directed local governments to get more specific about the anticipated income levels of future residents, and “make adequate provisions” for the future housing needs of those residents. An appeal brought by the land use advocacy nonprofit Futurewise and two Mercer Island residents argued Mercer Island didn’t do that.

The hearings board found that Mercer Island’s move to allow a few additional stories of height on potential new buildings within its Town Center neighborhood close to I-90 didn’t go far enough in accommodating those expected future residents, and that the City assumed much higher rates of affordable housing production than Mercer Island has historically seen. If Mercer Island decides against appealing the decision, it will have a year to comply with the new state requirements.

In clarifying what cities are required to do — and can’t do — to comply with HB 1220’s new requirements, the board set a strong precedent for future challenges to local growth plans, and other cities around the region appear to be taking notice.

In Bainbridge Island, where city leaders are months behind schedule in adopting an updated growth plan, the Mercer Island ruling is likely to send city officials sharpening their pencils to ensure they’re in compliance. At a meeting earlier this month, the Bainbridge Island City Council enlisted the help of City Attorney Jim Haney to come to grips with the ruling’s implications in their city, which is facing very similar targets for accommodating lower-income housing as in Mercer Island.

Out of the nearly 2,000 new units of housing Bainbridge needs to plan for through 2044, around half need to be geared toward families making at or below 80% of Kitsap County’s median income — around $77,000 for a family of two. Within Bainbridge Island itself, the median income is more than double that. A median Bainbridge home currently sells for $1.4 million, according to data from RedFin.

“The growth board very clearly said the game has changed from what it was prior to the enactment of HB 1220,” Haney told the council. “You are now required to actually plan for and plan to accommodate affordable housing, and it’s no longer the game of, we’re going to encourage affordable housing and rely upon that encouragement to get it.”

HB 1220’s affordability requirements have already become a well-known concept on Bainbridge Island. Incentivizing more affordable housing within the denser Winslow area dominated discussions around the city’s 20-year growth plan. So far the Bainbridge Island planning commission has held nearly 20 meetings fine-tuning that plan, with no end in sight.

Meanwhile, a plan to directly help to fund 92 units of affordable housing near the state ferry terminal in Winslow has been subjected to considerable pushback, which doesn’t auger well for the city’s ability to actually scale up more projects like it. Last week, the Bainbridge Council voted 6-1 to ask the project’s developer, the Low Income Housing Institute, to come back with a proposal for 70 units instead.

Haney spelled out the fact that the precedent set in Mercer Island actually requires cities to back up their plans for potential affordable units with concrete plans.

“The growth board is saying that if you’re going to rely on a publicly funded incentive program to provide some of the affordable housing that you’re talking about, you need to fund that program,” Haney said. “You cannot simply say in your plan, okay, we recognize that the land values are so high that in the city — which they are in Mercer Island and which probably applies to Bainbridge Island as well — you can’t just say, well, there’s we’re going to have to provide public incentives, somehow. You have to actually have a plan to provide those public incentives to make it work.”

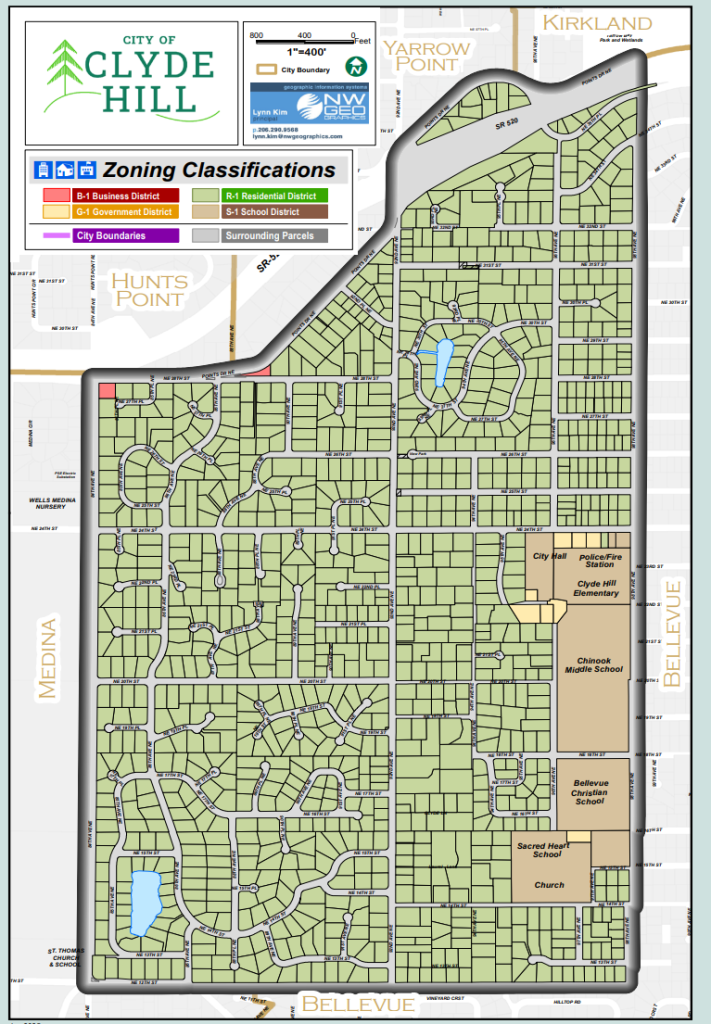

In Clyde Hill, one of the Seattle metro area’s smallest cities, the new ruling is also clearly making waves. While the city of 3,000 residents tucked between Medina and Downtown Bellevue had already adopted a Comprehensive Plan this spring, it too was challenged by Futurewise for not being in compliance with the new state requirements. An official hearing hasn’t yet been held, and the City and Futurewise are still in negotiations around a potential settlement. Clyde Hill is also in conversations with the Puget Sound Regional Council, which certifies local growth plans, around potential changes.

Clyde Hill is clearly trying to figure out how to get in compliance without direct state prompting, but that may prove to be a tall order. Its city government is in the midst of a tumultuous period, with Clyde Hill Mayor Steve Friedman announcing plans to resign in early September. His departure comes among heightened concerns around the city’s long-term financial solvency, and after a standoff between the city council over how to approach those issues that saw Friedman veto a decision to eliminate Clyde Hill’s city administrator position, which likely would have destabilized Clyde Hill city government.

While Clyde Hill’s 20-year housing growth target, allocated by King County, is just 10 units, the city’s land use framework is essentially designed to lock out any potential new lower-income households, putting the city at odds with HB 1220’s basic framework. All of the affordable housing the city has supported, via contributions to A Regional Coalition for Housing (ARCH), has been built outside city limits.

At an early August meeting, Clyde Hill councilmembers discussed a list of “recommended actions” to bring the city into compliance. When it comes to housing, the document was the first confirmation that the city’s administrators are considering making zoning changes to respond to these state requirements, creating areas in the city where an affordable apartment building could potentially be built with local or state subsidies.

“[A] Proposal [is] currently under review to establish new regulations for new zoning districts of higher densities, program options through ARCH membership, and support private/public partnership programs by Council in concert with response to PSRC certification concerns and Futurewise action again City at GMHB,” the document stated.

In a statement posted to the city’s website, City administrators confirmed that it was reviewing the Mercer Island decision, declining to respond directly to The Urbanist’s questions.

“That decision provides welcome clarity to all cities about how state requirements apply when planning for affordable housing,” the post stated. “Clyde Hill remains committed to proceeding thoughtfully and in full compliance with state mandates, and to supporting the development of affordable housing both locally and through regional efforts such as our membership in A Regional Coalition for Housing (ARCH). As this work continues, resident feedback will play a crucial role in shaping how Clyde Hill approaches the path ahead.”

But city leaders are far from united on a path forward, with multiple councilmembers pushing back on the idea of making substantive changes, and pointing to the city’s small size and its current financial situation.

“Futurewise appears to have a particular vision for Clyde Hill, which represents about 1/10th of one percent of the King County[‘s] 1,000,000 residences, and as most are aware, our City has experienced financial deficits for years,” Councilmember Steve Sinwell stated in a document framing his viewpoint ahead of the meeting. “It is premature to commence any meaningful effort or incur consulting fees on contemplating any updates of the Clyde Hill Municipal Code that seek to achieve consistency with the City’s adopted 2024 Comprehensive Plan.”

“Given that the City is forecasted to run out of money by 2030, I’m at a loss to understand how we could possibly encourage affordable housing via incentives,” Clyde Hill Councilmember Wissner-Slivka wrote an email sent in lieu of her attendance at the meeting. “And before the City allocates any resources to adopt code that would enable new [i]nclusionary zoning districts of higher densities, I believe that we need to better understand how current residents would be impacted.”

Bainbridge Island and Clyde Hill will be far from the last cities to reckon with the new state framework forcing cities to act more aggressively when it comes to planning for affordable housing. But, like crash-test dummies, they will take the first impacts and provide lessons for everyone else.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.