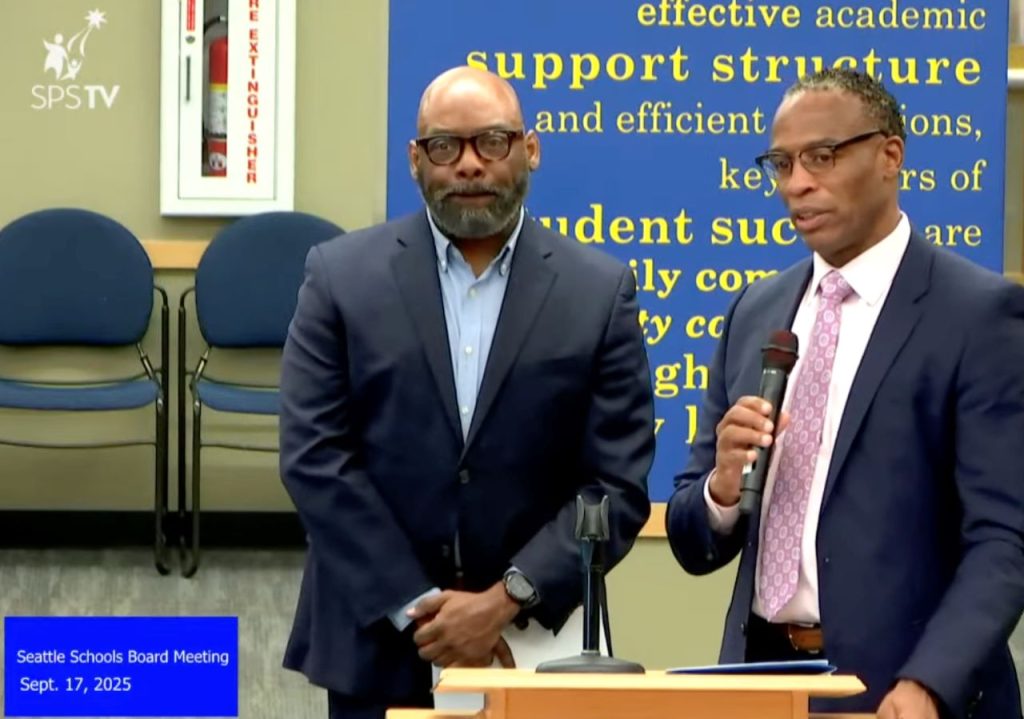

Last week, the Seattle School Board was scheduled to make a final vote to decide whether Garfield High School will pilot a “Student Enforcement Officer” (SEO) program in collaboration with the Seattle Police Department (SPD) during the new school year. While the pilot is supported by Seattle Public Schools (SPS) interim Superintendent Fred Podesta and Garfield’s principal Tarance Hart, the school board voted to delay the vote until the next board meeting on Wednesday, October 8.

Board director Joe Mizrahi asked for the extra time, saying he’s working on an amendment to bridge the gap between those who want a police officer back on Garfield campus and those who would feel unsafe with a police officer in the school.

Mizrahi didn’t give any further details about his proposed compromise.

Garfield was the only high school in the district to have an SEO before the school board adopted a moratorium on using SPD officers inside schools in 2020 in the wake of the George Floyd protests. The board’s resolution called for replacing police officers in schools with other services and mentorship opportunities.

The Urbanist previously reported that school board director Liza Rankin said one of the primary concerns about having police officers on school campuses was the requirement that they carry firearms. The Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) contract requires on-duty officers to be armed.

The vote on the Garfield SEO pilot would not otherwise change the moratorium. Eventually, the school board could return the power to make decisions about police officers in all schools to the district superintendent.

Rankin is one of only two current board members who was serving in 2020 and voted in favor of the moratorium.

Mizrahi was appointed to the school board in April 2024, and is currently running to retain the seat. In addition to wanting to find a compromise, he’s concerned there is still confusion around the school board moratorium. At times, SPD has appeared to interpret the moratorium to go beyond an end to the SEO program and mean police officers cannot go inside school buildings unless someone has called 911.

“This sense that the moratorium was somehow barring police officers from interacting with school buildings like normal human beings, as you said, is very problematic to me,” Mizrahi said. “I wanted to have language that would make it clear that the moratorium was never intended to do that and nor should it be read that way going forward.”

Change of course

Originally, the district suggested lifting this moratorium in order to enable the Garfield pilot this year, but board members objected to this during their August meeting. Certain members expressed the desire to be responsive to Garfield’s needs, while taking the necessary time to think through a system-wide change and conduct community engagement.

“I think that the concerns in the rationale and the concerns around the positionality of SPD in this agreement are completely warranted by [the] community,” board director Brandon Hersey said. “Does that mean that we shouldn’t do it? No, that’s not what I’m saying. But I do think that that is just another example for me [of] why it’s so critical that we decouple the situation that is occurring at Garfield and the support that we can potentially provide for that community from a full-throated approach to this, full stop, within our system.”

At that time, Rankin also expressed confusion as to why the SEO needed to be inside the Garfield building when the majority of safety threats are coming from outside.

“[The purpose of police officers] is not to police students. It’s not to handle discipline issues in buildings,” Rankin said. “It’s to protect from threats coming into the community.”

Rylan Springer, a recent Garfield graduate who spoke at a rally before last week’s school board meeting, agreed with Rankin. Springer said she had asked a few weeks ago for a school resource officer at Garfield outside of the building, with community control over said officer.

Having an SEO remain outside the building at Garfield would be one potential compromise to the pilot. Another possibility would be to have a community resource officer in the school instead of a sworn officer. A community resource officer doesn’t have to be armed, but would still allow SPD to have a presence at the school.

Arron Murphy-Paine, father to Amarr Murphy-Paine, who was shot and killed in Garfield’s parking lot in June of 2024, spoke at a rally before the most recent school board meeting.

“I do like what I see: us standing here together, letting them know that the community needs to be a part of those decisions that are made by the police department, by the City of Seattle, by Seattle Public Schools and the school board,” Murphy-Paine said.

Another issue is deciding how to evaluate the Garfield pilot program. As of the end of August, there didn’t appear to be a specific plan as to how to measure its success, even if the board voted to approve it.

“We haven’t completely thought through how we’re going to measure the pilot, how at the end of the year we can know whether it’s successful and we want to renew, so again, the policy recommendation is broad,” said SPS Accountability Officer Ted Howard.

Howard said he thought it would take the district “a while” to figure this out.

The school district has planned to implement many new safety measures this school year, including hiring more safety and security experts wearing recognizable uniforms, replacing the security fleet, installing a new suite of automated tools to help manage school security cameras, trying a new visitor management system and better emergency notifications, and installing security vestibules that allow two-part entry.

The district is also engaging in a new pilot of weapon detection systems.

School board members brought up that with so many new safety measures being implemented during the same school year, it might be difficult to determine which ones are effective, especially if a new SEO pilot is also added to the mix.

Mizrahi asked if the district has baseline metrics, for example, for how many violent incidents occurred in the last school year.

Howard responded that while the district collected data last year, they don’t think it’s reliable because the recording system is difficult to use, hence why they’re replacing it. “The numbers seem suspiciously low,” Howard said.

If last year’s numbers are already low, it is less likely the year-long pilot would show any improvement to those numbers.

School board director Michelle Sarju insisted that the district utilize professional researchers to collect and analyze data about the efficacy of Garfield’s SEO pilot program.

“Back this up with effective research because at the end of this, what we want to know is, is this beneficial for students? At the end of the day, our job at a public school district is students,” Sarju said. “Does this really bring safe, emotional, physical, safety and security to the building, to the surrounding area? But most of all, our students, and particularly those who have been disproportionately affected by policing in schools, right? It is a school to prison pipeline. I’m not arguing with nobody about that.”

Delays abound amidst concerns

Podesta implied that the board’s decision to delay Garfield’s SEO pilot further might harm the district’s relationship with SPD. However, both SPD and the district have been responsible for their share of the delays around bringing SEOs back into Seattle schools.

Rankin and district staff exchanged several emails in summer of 2024, in which Rankin appeared to be trying to gain clarity about the board’s role and set expectations for what work she expected the district to do in order to prepare for any kind of return of SEOs.

Hersey noted at August’s meeting that there had been a very recent, last-minute offer of a meeting with SPD Chief Shon Barnes, even though the district had been talking about the possibility of a new SEO program for a long time.

The Urbanist also obtained an email written by Kerry Keefe, SPD’s Director of Program Development, who served as Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell’s director of public safety until spring 2024.

In the email, sent in mid-February of this year, Keefe wrote to various members of SPD and City Hall that SPS had been given a copy of the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with SPD in December of 2024. She received a review of the MOU draft from SPS two months later in which the district had neither accepted all edits nor made notes on any open issues in order to move along the collaboration.

“Not sure where to go with this,” Keefe wrote.

The district has been discussing the proposed MOU with SPD with the Garfield community this summer.

Principal Hart urged the school board to limit any further delays on the pilot.

“In order to have an adequate time to do a full pilot and to really engage students and look at the data, having a longer period of time to do to do that and to get that resource on campus as soon as possible is something that I think I’m definitely in favor of, and I think that that’s what we need at Garfield,” Hart said.

Board directors discussed the possibility of holding a special meeting before October 8 to make their final vote on the question.

Meanwhile, the Seattle Student Union continues to oppose the return of police officers to SPS.

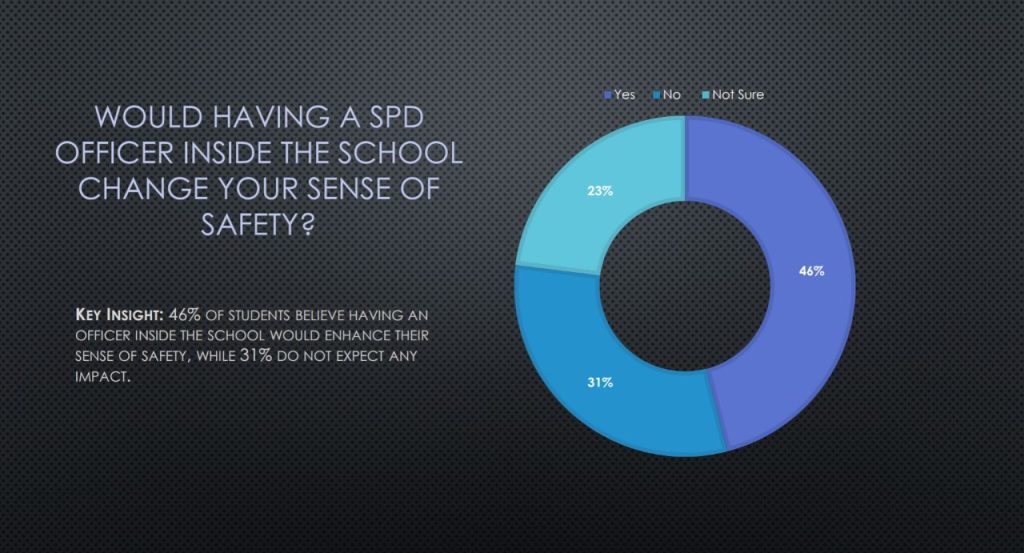

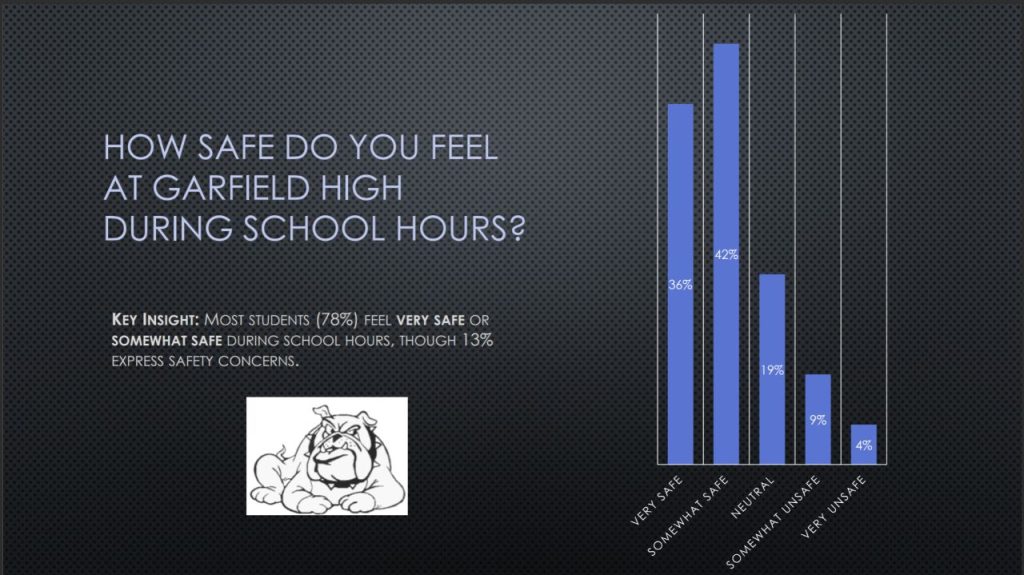

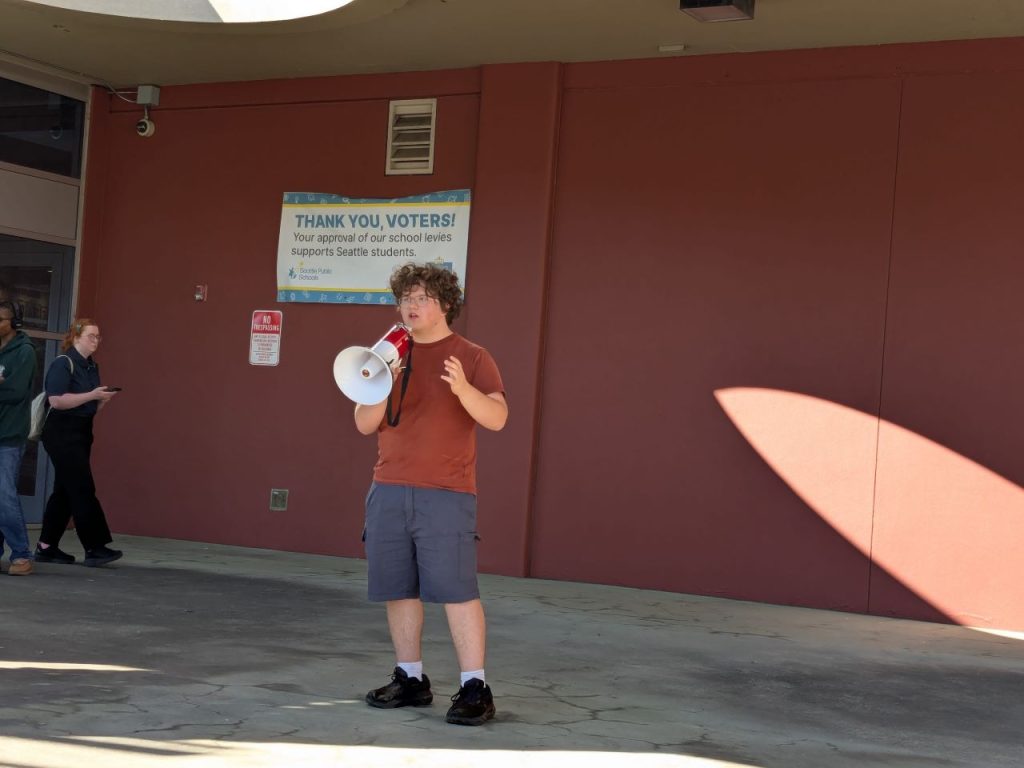

Leo Falit-Baiamonte, a student at Nathan Hale High School, said that several school board members, as well as Harrell, are saying that a survey taken by Garfield students shows support for a police officer at the school. But, Falit-Baiamonte pointed out, only 32% of the student body responded to the poll. Meanwhile, no demographic data is provided for who responded and who did not.

A recent newsletter from Garfield’s Parent-Teacher-Student Association (PTSA) appeared to challenge the Seattle Student Union, writing that while the group is “entitled to their perspective, their statements should not be taken as representing the views of Garfield students, staff, or families.”

Falit-Baiamonte said many students from Garfield’s PTSA reached out to the Seattle Student Union saying that the PTSA was not representing them.

“Students at Garfield have been working at us, and your students across SPS are speaking out because there are many issues this raises down the line,” Falit-Baiamonte said. “How will data be collected to make sure if this is successful or not? What will prevent this from going to other schools? And also fear that if it does go to other schools […] how will they protect us from the Trump administration?”

Falit-Baiamonte expressed concern that SPOG has endorsed Rachel Savage, a supporter of President Donald Trump, in a current Seattle City Council race and that SPD “attacked pro trans protesters and also have assisted at the Northwest Detention Center.”

Next steps

The SPS school board will vote on whether to allow the Garfield SEO pilot at their meeting on October 8. Mizrahi told The Urbanist more details about his amendment will be available about a week before that meeting.

Come November, voters will be deciding whether to pass the Families, Education, Preschool, and Promise (FEPP) levy. While the City has agreed to pay for the first year of the Garfield SEO pilot, the FEPP levy could potentially fund future years, as well as any SEO pilots at other schools.

If the FEPP levy passes, the Seattle City Council will begin discussing a spending plan for the levy dollars in the first half of next year. With the makeup of next year’s city council currently up in the air, and primary results that suggest two positions might go to more progressive candidates, it’s difficult to predict whether the council will allocate money from the levy to SPD. They could instead allocate money to other safety measures, such as gun violence prevention programs, mentoring and skill building programs, and more support for student mental health.

Falit-Baiamonte said the Seattle Student Union will be taking a great interest in these discussions.

“First of all, having police officers part of the FEPP levy is an exact failure for what the FEPP levy is supposed to do. It’s about promise. It’s about what can students be. And putting that money towards discipline is the opposite of what that should be,” Falit-Baiamonte said. “This is money from people’s property taxes that’s supposed to go to our underserved schools, our underfunded schools that need a lot more funding. Instead, that money is going to go to police officers.”

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.