King County Councilmember Rod Dembowski wants King County Metro to explore dropping transit fares, putting forward a directive for the county’s budget creating a fare-free pilot program in 2027 that includes at least two bus routes. An idea put forward in response to the fare revenue becoming a much smaller slice of Metro’s overall sources of financial support since the Covid-19 pandemic, Dembowski’s proposal follows in the footsteps of other jurisdictions around the country that have implemented or are are exploring free bus service.

While fare collection does come at a cost for Metro, ditching the farebox could cut off a substantial income stream for Metro, which faces systemic revenue problems over the long-term.

Interim Executive Shannon Braddock’s proposed budget already proposed spending $3.9 million over the next two years to start to transition Metro to a cash-free agency, a move that would allow the agency to stop maintaining fareboxes on coaches, paying for cash handling, and dealing with paper transfers. But Dembowski’s proposed budget proviso would try out fully ditching fares, a move he says could increase ridership and improve equity within transit-dependent parts of the county.

“I continue to be interested in the value of collecting fares compared to the cost incurred to do it, to manage it, for fair enforcement, and then all the other money that we spend on climate reduction work. The theory advanced here on dialing back our zero emission program is we’ve got to get more riders on and that delivers good climate benefits, right?,” Dembowski said during a budget panel last week, referencing the proposed budget’s pivot away from high levels of spending on vehicle electrification. “Jurisdictions that have eliminated fare box fare collection, ridership goes way up. It’s a direct shot in the arm to boosting ridership.”

In 2025, Metro expects to spend $24.5 million on fare collection to recoup $80 million in fares, with $5 million of that going to fare enforcement personnel, part of Metro’s larger Transit Service Officer (TSO) program. Another $4 million goes to maintain fareboxes and $280,000 to maintain paper transfers. The rest of those dollars are spent on the regional ORCA system and on reduced fare support via the Regional Reduced Fare Permit, ORCA LIFT, and fully subsidized fare programs. In 2019, fare collection revenue was twice what’s expected this year, at $163 million. Despite a 25-cent increase in rider fares that took effect this fall, fare revenue is only expected to increase to just over $100 million by 2027.

If Metro were to remove fare revenue from its balance sheet, that move would actually represent a disproportionate benefit to businesses who pay for monthly passes used by their employees. Between July 2023 and April 2024, ORCA business passport accounts made up over 50% of Metro’s revenue from fares, even as those riders only accounted for around a quarter of Metro boardings over the same time period.

While Dembowski didn’t directly reference other cities that have tried going fare-free, a pilot program on a few routes would mirror Boston, which dropped fares on one bus route in 2021 and added two more into the pilot the next year. Boston backfilled fare revenue using federal Covid relief dollars, while no direct funding has been identified to pay for a fare-free pilot at Metro.

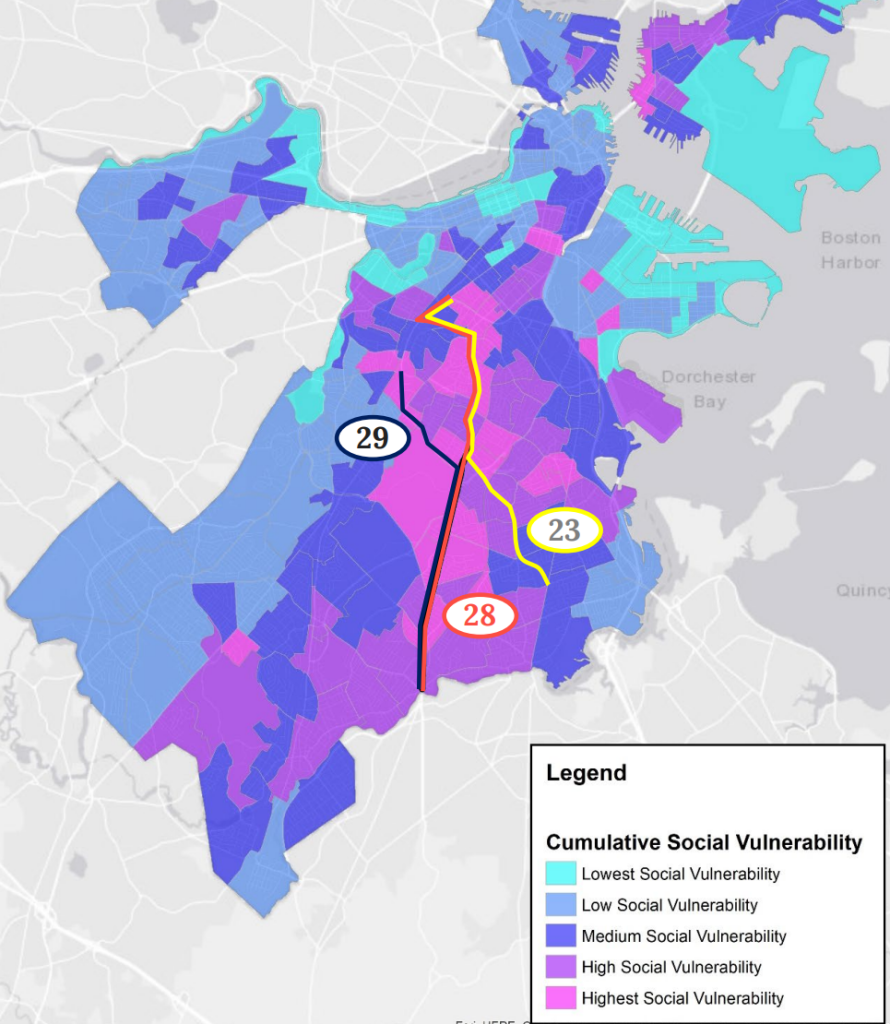

The three Boston bus routes, operated by Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), did see bigger ridership gains compared to the system as a whole in the wake of dropping fares. Between 2021 and 2022, the MBTA bus system got 7% closer to pre-pandemic ridership levels, whereas ridership on the fare-free Route 23 and 29 jumped 20% closer to pre-pandemic levels. The Route 28 — the first one to go fare-free in 2021 — had already fully rebounded to pre-pandemic levels.

As for the impact on climate emissions — a benefit seen when transit riders ditch their cars for the bus — Boston’s pilot confirmed what has been seen elsewhere in the United States: very limited benefit. Just 5% of MBTA riders said the additional bus trips they made would have been made by car, a lower number than walking and biking trips.

“There’s no evidence at all that cities introducing fare-free public transport have seen their car traffic reduced,” Mohamed Mezghani, the secretary general of the International Association of Public Transport, told Bloomberg‘s David Zipper in 2022. “Most of the [new] people taking public transport used to walk.”

Earlier this year, the MBTA delivered a report to the Massachusetts legislature that strongly pushed back on the idea of continuing a limited-route pilot for fare-free programs, particularly dropping fares without identifying a long-term revenue source to make up for them.

“Route-specific pilot programs are geographically inequitable, difficult to communicate, and work against MBTA goals of providing equitable and consistent transportation across the Authority’s entire service area. The intended short-term nature of fixed-duration programs also generates challenges when the time comes for the programs to end, risking the creation of unfunded initiatives that remain costly beyond the programs’ intended sunset dates,” the report stated. “[G]iven the cost of systemwide fare-free bus services […] and the limited funding sources available to the MBTA, any additional expansions of fare-free bus service should be accompanied by permanent, dedicated funding that avoids the risk of leaving the MBTA with unfunded service commitments in the future.”

Another potential benefit of not collecting fares, decreased dwell time at stops, was actually not seen in Boston as the increased ridership cancelled out the gains that came from riders spending less time fumbling at the cash slot. Metro would likely see maximum reductions in dwell time by simply moving toward ORCA-only payment, which is already planned.

In Washington State, eight transit agencies are now fully fare free. But the largest of those agencies, Intercity Transit in Thurston County, carried fewer than 5% of the riders on fixed-route service that King County Metro did in 2023. Few large transit agencies in the US have gone fully fare-free, in large part due to the fact that many are heavily dependent on local revenue sources that are also regressive and politically unpopular to increase. While going fare-free is credited with playing a big role in Intercity Transit surpassing 2019 ridership levels in 2024, the agency has also been increasing service, making its routes more appealing choices for riders and making it impossible to separate out the impact of ditching fares.

This debate over fares at the county council is happening against the backdrop of the County’s Transit Safety Task Force, which earlier this month proposed a slate of recommendations to improve the safety of operators and riders across the countywide bus system. Braddock’s biennial budget includes funding for 275 Transit Service Officers (TSOs) as part of an attempt to beef up security on coaches, but fare enforcement activities are only a small part of what those officers spend their time on. Even without collecting fares, there are no indications that Metro’s annual budget for TSOs would be reduced as those officers likely get reassigned to security functions.

Dembowski framed his desire to advance this issue as coming from a place of trying to decrease the burdens placed on Metro riders with the greatest need. But many riders would likely want Metro to remain focused on its service expansion goals, which aim to bring faster, more frequent, and more reliable transit into more areas of Washington’s largest county. Surveys have shown this is a top priority for riders.

“I took a ride on the [Route] 160 yesterday from Auburn all the way up to Renton, and I watched, there are still people paying with cash fares. There are young people getting on, and they ride free if they’re under 18. Do you get into a dispute with your operator about, are you under 18, are you not?,” Dembowski said Tuesday as budget deliberations continued. “All of the barriers we put up for the free ticket program, for the ORCA fare card program, it is just: if you’re trying to get through life, and you’re on the lower end of the economic scale, and the bus is an important piece of your life. If we take away all that — I’m observing, I’m not advocating yet — but you could build a system, or even maybe some routes, where folks’ life gets a lot easier.”

With any pilot program not coming until 2027, the debate over this issue is likely only just getting started.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.