Last week, the Seattle Public Schools (SPS) School Board voted against allowing a year-long pilot program to install a police officer inside Garfield High School.

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell, Seattle Police Department (SPD) Chief Shon Barnes, and interim SPS Superintendent Fred Podesta all supported the “Student Enforcement Officer (SEO)” plan to return police inside Garfield, as did Garfield’s principal, Tarance Hart. However, the motion failed in a 5-2 vote.

The proposal would have amended a moratorium on police officers in schools passed by the school board in 2020, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. A yes vote would have allowed Garfield to enter into an agreement with SPD for a limited pilot.

Directors Liza Rankin and Brandon Hersey, the only two board members serving during the 2020 vote, were also the only two votes in favor of the new proposal.

The vote had been delayed from the board’s September meeting after School Board Director Joe Mizrahi asked for an extension to complete an amendment to the proposal.

Mizrahi’s amendment clarified that SPD officers have access to school buildings in the case of emergencies and other approved circumstances. The amendment also clarified that SEOs are meant to respond to external threats but not act in a disciplinary capacity toward students and that an internal complaint process would be set up in the school. Finally, it stipulated that the pilot wouldn’t be extended beyond one year or expanded to more schools until the superintendent presented the board with an analysis of effectiveness, budget impacts, and alternatives to armed officers inside schools.

“These amendments are intended to be responsive to the community concerns and also clarify our values as a board,” Mizrahi said.

The amendment passed unanimously, but after further discussion, the proposal as a whole still failed.

Community objections and confusion

During public comment, several community members spoke against the new SEO program. Makena Gadient, a special education teacher, pointed out that the SEO would be armed, bringing a gun into the school. Gadient said the SEO wouldn’t have access to students’ Individualized Education Programs or be trained in the Crisis Prevention Institute’s non-violent restraint training.

“I don’t know why we’re moving backwards,” Gadient said.

Also giving public comment were two parents of former Garfield students who were against bringing a SEO back to the school. Amanda Thornwell spoke about the harm the former officer at Garfield did to her son when he was a student there, pressuring him not to speak to the press about a hazing incident he’d witnessed. Elijah Smith brought up the school to prison pipeline and the issues her son had with Garfield staff.

“This interest of bringing police into the schools is not going to solve the problem,” Smith said.

“The district keeps asking forgiveness rather than for permission,” said Oliver Miska, who works in education policy.

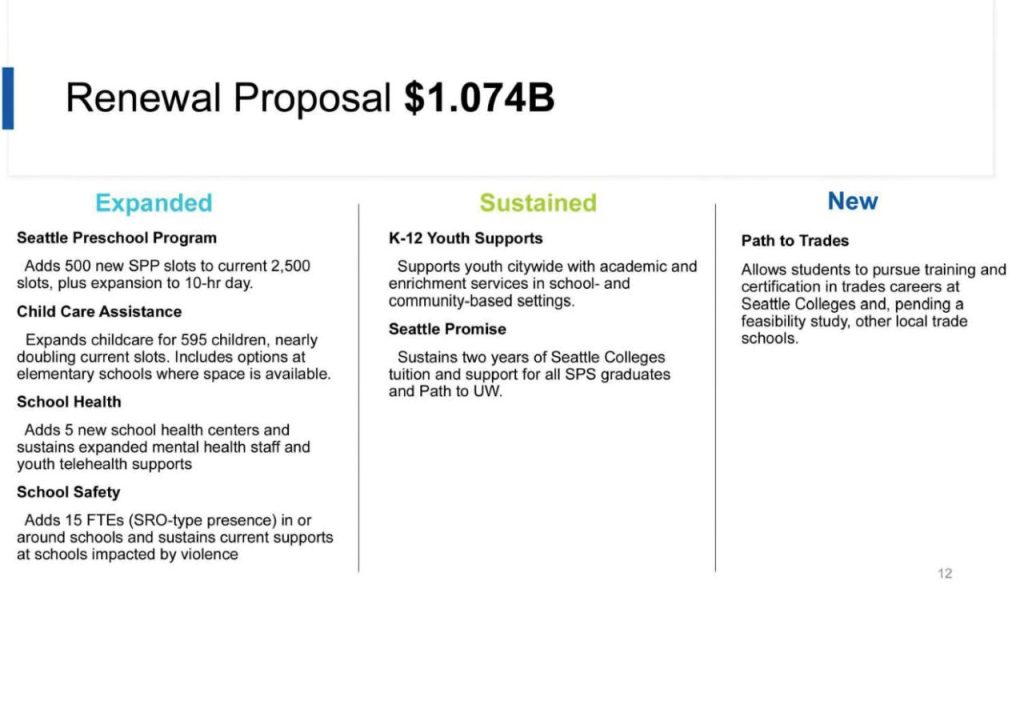

Miska shared documents obtained through a public disclosure request with The Urbanist, which included a “final approved deck” of slides prepared by the Seattle Mayor’s Office for a presentation to the city council on the Families, Education, Preschool, and Promise (FEPP) levy, on the ballot this November. Sent by Deputy Mayor Tiffany Washington on March 10, one slide in the deck said that the levy would add 15 full-time equivalents (FTEs) as Student Resource Officer (SRO) type presences in or around schools.

The slide was also shared with Councilmember Martiza Rivera, who chairs the select committee on the levy.

Later emails showed the slide being deleted from the final deck by April 29.

“We have no evidence of whether or not [the proposal has] been removed, whether or not it’s been included. [It] just speaks to the lack of transparency from the Mayor’s office,” Miska said.

Prior to the 2020 moratorium, police officers only served in five of Seattle’s schools (Garfield being the only high school), so introducing 15 officers into schools would represent a major expansion rather than a return to the pre-2020 status quo.

“Our office has been in conversation with Seattle Public Schools about reintroducing a school resource officer program since August 2024, and Mayor Harrell has been consistent about his support for this approach and wanting to co-create a new program with communities,” Callie Craighead, a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office, told The Urbanist.

“Assuming the levy renewal is passed by the voters, any spending allocations would be decided in the FEPP Levy Implementation and Evaluation Plan, which will be submitted to Council in early 2026,” Craighead continued. “So while we made estimates about what a reintroduction of this program could look like, any spending allocations wouldn’t be decided until the I&E plan.”

Contentious decision

Alicia Spanswick, the Garfield Parent Teacher Student Association safety lead, explained that the new proposal uses the term SEO instead of SRO on purpose.

“We’re trying to build a brand new program that is completely different from the traditional SRO model and what we had in Seattle before the moratorium,” Spanswick told The Urbanist.

Spanswick spoke of the benefits she thought a new SEO program might bring to Garfield, including a direct line to police dispatch, better emergency preparedness, a deterrent effect, and the opportunity to build positive relationships between law enforcement and kids.

Spanswick said she was disappointed the proposal didn’t pass but blamed a lack of trust and transparency on the part of SPS rather than the board.

“Whether it’s intentional obfuscation on the part of the district or if it’s laziness, I don’t know,” Spanswick said.

The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between SPS and SPD is a chief point of both confusion and contention. A draft MOU was attached to the proposal, and parents and community members were concerned that it didn’t reflect input into the MOU provided by the community.

Spanswick pointed out that there is a line in the draft MOU that would allow SEOs to investigate criminal activity on school grounds, which she called a slippery slope. She’d prefer to see other police officers brought in to do any kind of criminal investigation.

The MOU also has two references to SEOs being able to take law enforcement action when there is significant risk to property, not just harm to others.

“No one’s asking for police intervention because of property damage,” Spanswick said. “We’re not asking for police intervention to stop students from doing these sort of normal, if naughty, teenage behaviors. We’re trying to prevent neighborhood violence from typically adults or much older teenagers from bleeding onto the campus.”

“[The MOU] looks exactly like something that’s in alignment with a model policy recommending SRO positions. The problem is, I think what’s been missing with this whole conversation is what we want at Garfield is not a traditional SRO,” Director Liza Rankin told The Urbanist. “We want a designated officer who can coordinate with the school and the police department, who knows our students and knows our school policies.”

Pressure on the board

During the board’s discussion before the vote, school board directors expressed frustration with the process and a lack of trust in the district, the City of Seattle, and even one another.

“This has just been a mess,” Hersey said. “It’s been a complete mess in terms of sorting how do we provide a school and community with the opportunity to help their students and their staff and anybody who is associated with the Garfield community feel safe.”

“I think what the situation represents is when you start from a place of lies, deceit, hiding things, not being authentic, this is where we end up,” Director Michelle Sarju said.

Had the board passed the Garfield pilot proposal, they wouldn’t have been given the opportunity to vote on a final MOU between SPD and SPD. That MOU would instead need to be approved and signed by Podesta on behalf of the district.

“I also want to be really clear that the disproportionate discipline and the culture that we have in our buildings, this MOU with an officer on one campus is not the tipping point of where there are problems,” Rankin said. “We have an underlying culture of being punitive and discriminatory towards children with or without the police.”

Podesta said the language in the MOU needed to be fleshed out to be completely clear that student behavioral issues are to be handled by SPS staff.

“The intention behind the memorandum of understanding, I think we have agreement with SPD on, is the only time an SEO would offer any services like a regular patrol officer would do, is in a circumstance where we would have called 911,” Podesta told the board.

Podesta also said the district hadn’t been spending much time working on the MOU before the board meeting since they didn’t know which way the vote would go.

“The superintendent shouldn’t sign an MOU that conflicts with our policies,” Rankin told The Urbanist. “[Other school board directors] were really nervous and worried that whatever agreement was ultimately reached wouldn’t honor our direction.”

During the board meeting, Sarju, whose term ends this year, spoke of her distrust of the district.

“I always have cared about Black kids, and I’m going to go out caring about Black kids,” Sarju said. “My colleagues know I talk about Black kids all the time, because until y’all correct the disparities once and for all, we are not standing on equal ground. Too much data that says having a police officer in a school creates more disproportionality, not less.”

“The lies and deceit for me are the line in the sand,” Sarju continued.

“I really struggled with my vote,” Rankin told The Urbanist, “and I can completely understand why colleagues just didn’t feel comfortable voting yes because it was so convoluted, and I also voted yes because we have to have these conversations and figure out how we all work together as a whole city.”

A political decision

“I’m hoping that from this point forward, we can stop the political wrangling and put kids first,” Sarju said before the vote. “This should not be about winning an election or not. This should be about what’s best for kids.”

But the issue of bringing officers inside schools is one that mayoral candidates have been asked on the campaign trail. At a recent debate at Seattle University moderated by KOMO’s Chris Daniels, Seattle University student Diego Borromeo, and professor Joni Balter, both Harrell and Katie Wilson, the frontrunner in the mayor’s race, were asked if they support having an SEO at Garfield.

“If the students want it, and I believe 70% of students want it, if the principal wants it, I know he wants it, then we think that this would be a good relationship,” Harrell said. “So yes. However, I’m very willing to go, certainly not a gun and badge, an unarmed response. I want these kids safe.”

The recent poll of Garfield students did not have a question specifically asking if students wanted a police officer inside the school. Because only 32.2% of total Garfield students responded to the poll, with no demographic information about respondents available, it is difficult to draw definite conclusions from the poll about how students feel about the proposal.

In addition, the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) contract requires on-duty police officers to be armed.

“The research does not support the notion that armed officers in schools lead to increased safety, and that it may actually be harmful, especially for minority students,” Wilson said. “So that gives me pause. At the same time, and it’s very important, obviously, what students feel, what parents feel, what administrators feel, and so I think there needs to be, and I understand that there is, a conversation going on about that.”

If the FEPP levy passes in November, the city council will hammer out a more detailed spending plan for the levy’s safety investments later next year. How the Council and the Mayor’s Office proceed will also depend on election results.

However, the ultimate decision as to whether to implement an SEO program in Seattle schools, starting with a limited pilot at Garfield, is in the school board’s hands. Four of the seven school board seats are up for election in November, with Hersey and Sarju not seeking reelection.

“We’re going to have to regroup and figure it out,” Rankin said. “But I think the most important thing, no matter what, is that it’s not about different people’s political benefit. We have got to hear and support the Garfield community.”

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.