In the 1990s, I worked on one of the best and boldest implementations of Bill Bratton-style community policing bar none. After leading successful reforms as police chief in New York City, Los Angeles, and Boston, Bratton is considered “one of the leading architects of modern policing.” (For a brief explanation of why, see the note at the end on “Bratton’s Pivot from “Three R’s” to “Three P’s.”)

In New Haven, Connecticut, a sergeant and a team of police officers were assigned to each neighborhood with the time, talent, and a mission to solve the highest priority crime problems in each one. It made a real difference.

Here in Seattle we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to do even better. That’s how anti-bad guy, pro-good cop, and taxpayer-friendly Seattle mayoral candidate Katie Wilson’s public safety platform is.

In contrast, Harrell’s plan would completely blow our chance.

If you can’t square this with what you’ve seen on social media, read in Harrell’s campaign literature, or god forbid Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) propaganda you had to suffer through, I urge you to read on.

The ground truth of the moment we’re in

Let’s start with the stone-cold facts that either candidate will inherit the day the winner is sworn in:

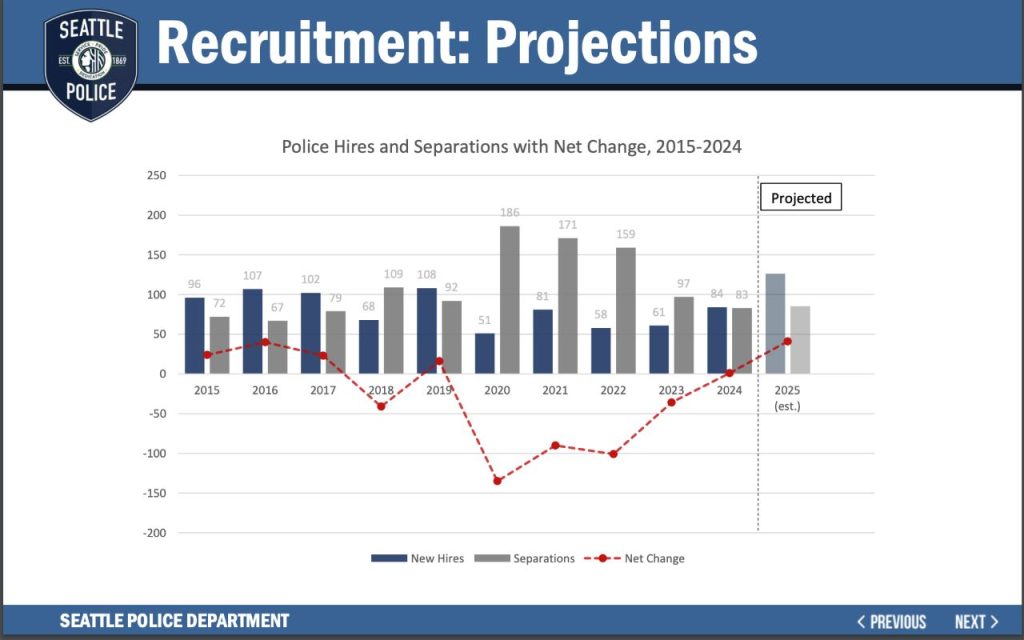

- Early next year, sworn officer staffing will be about 1,000 officers.

- Between 2017 (peak sworn officer staffing in Seattle) and 2019, Seattle Police Department (SPD) averaged 1,429 officers.

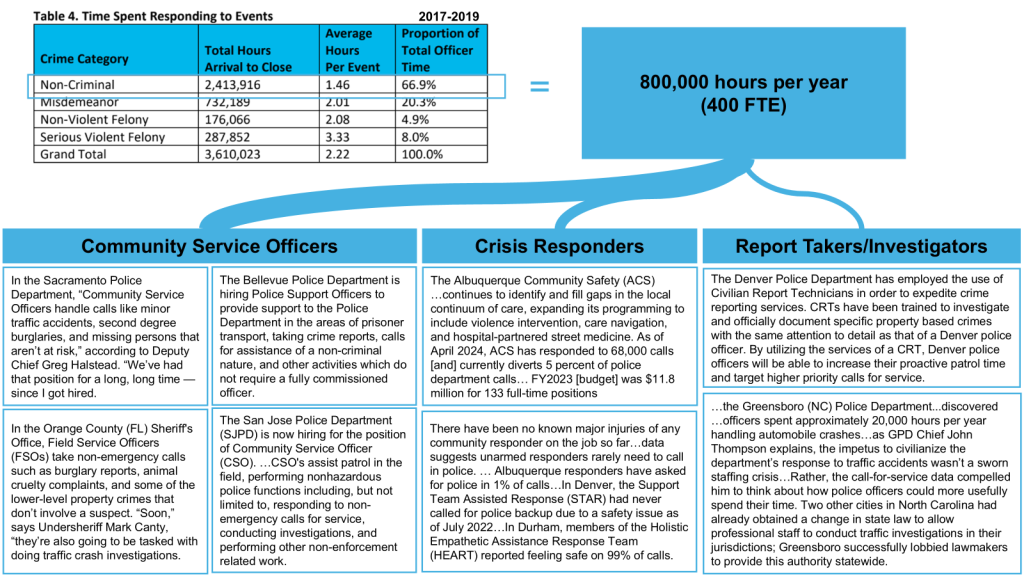

- During that same 2017-2019 period, the city’s analysis of computer aided dispatch data shows that sworn officers spent 2,413,916 hours on non-criminal calls for service. That’s an average of just over 800,000 hours per year, almost exactly 400 FTE’s-worth.

Aside from civilian crisis responders–the Community Assisted Response & Engagement (CARE) department — Harrell plans to ignore points two and three and recreate the status quo ante. Once again–to the benefit of bad guys, the detriment of good cops, and in a raw deal for taxpayers–we would burden a sworn force of 1,400 plus officers with lots of things civilian staff can do equally well for less.

To add insult to injury, Harrell just offered SPOG a contract that gives officers a big raise — a 42% pay increase in just five years–while hamstringing the deployment of CARE through a list of arbitrary restrictions.

One of the more head-scratching examples: if someone is having a mental health crisis on the sidewalk outside of a Safeway, CARE can be solo dispatched. But if they are just inside the Safeway, sworn officers must also be dispatched — a needless waste of officers’ time and talent.

But what’s more egregious is that Harrell is negotiating dispatch protocols with SPOG at all. Albuquerque’s CARE equivalent has handled more than 100,000 calls for service. They clearly know how to successfully and safely operate civilian crisis response and Seattle should simply be adopting their well-proven protocols rather than letting SPOG put an uninformed thumb on the scale.

Wilson in contrast understands the upside for all involved (well, except criminals) of building back better. From her platform:

Seattle’s CARE Department, our primary alternative response for crisis calls, has shown success — but its expansion has been stymied by a poorly negotiated police contract, which caps the department at just 24 civilian responders. We are still deploying highly paid, highly trained armed officers to mental health and other non-crime calls they’re neither suited to nor needed for — and many other jobs civilians can do, from directing traffic at events to taking down crime reports. This crowds out proactive police work and limits the immediate availability of officers to respond to crimes in progress.

Katie WIlson’s platform

Here’s the kicker, from which all good things follow: based on what other cities are already doing, hiring 400 civilian responders to unburden officers of all those non-crime calls will only cost as much as 300 sworn officers.

And that civilianization dividend would be a big deal.

Where we could go from here

At this point, I will ask you to focus on one fact and one happy assumption.

The fact is that Harrell’s plan is to staff up to more than 1,450 sworn officers and fund CARE team responders as a net addition on top of that. So it’s 100 percent certain Wilson wouldn’t need to come back to taxpayers for more than what her opponent is already committed to spending to implement a civilianization plan.

The happy assumption is that the civilianization plan is doable. The good news is that it is, as I’ll explain. But first I want to focus on the possibilities it unlocks.

If within the same public safety budget we were going to spend anyway we were to free up 100 sworn officers’ worth of salary, benefits, and overhead, we could do any combination of three things:

(1): We could go ahead and hire an additional 100 sworn officers. This would result in 200,000 more hours per year of sworn officer time focused on proactive police work and handling crime than the city has ever had.

It’s enough to staff every “Urban Village” with a best practice Bill Bratton-style community policing team of a sergeant and foot patrol officers fully dedicated to 100% proactive police work.

(2): Accountability for results is at the heart of Bill Bratton-style community policing. In my department, if you were a police officer and wanted to make sergeant, a sure-fire way was to reduce crime on your beat. If you were sergeant and wanted to make lieutenant, a sure-fire way was to reduce crime in the district (based on neighborhood) you supervised.

We could take the next logical step and offer annual cash bonuses for excellence at proactive police work and community policing where it’s needed most. It’s enough for (say) 200 of the best line officers and street supervisors to get as much as half their salary as an award.

Over the course of their career a great beat officer could earn more than $1 million in bonuses, making Seattle a magnet for the very best police officers and aspiring officers in the country.

(An albeit less exciting but more tried and true approach to achieving the same goal would be using the dividend to create a budget for master police officers and street supervisor roles. With a strong community policing track record, officers and sergeants could be promoted in place to continue frontline work at a higher base salary.)

(3): We could split the difference, allocating (say) half of the civilianization dividend to staffing 100% proactive teams that could take rotational assignments.

Little Saigon behind the eight ball? Ongoing trouble at Magnuson Park? Hot rod street takeovers on Capitol Hill? Teams could be assigned to take responsibility for hotspots and chronic problems until they are well and truly fixed.

And we’d still have a budget to reward excellent police work.

The cash bonuses are my idea, but community policing best practices are already in Wilson’s platform:

Pilot a problem-oriented, place-based model of public safety, assigning individual police officers and civilian responders to several specific neighborhoods to increase responsiveness and focus on reducing crime, crises, and disorder.

Why the right thing to do is obvious

The Bizarro World thing you need to internalize about the public safety discussion in Seattle right now is that the fact that sworn officers tend to get burdened with tasks that are neither proactive police work nor handling serious crime is something the profession has been wrestling with since the 1960s.

While the will and wherewithal to do something about it has varied by place and time, it was never, ever regarded as a good thing.

Getting officers out from under it was always regarded as a plus.

For example: the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice recommended the creation of an unarmed civilian position, a community service officer (CSO), within police departments in 1967.

The Worcester, Massachusetts police department proved community service officers could help (with majority approval of the role from sworn officers) in 1975.

I had an FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin with a feature article about civilianization on my desk, in a police department, in 1994.

Today, lots of cities and police departments are way out ahead of Seattle at unburdening officers from tasks that don’t require a gun and the power of arrest. The infographic below provides a mapping of how proven, already deployed roles in other cities could enable Seattle police officers to enjoy the same relief.

Civilian roles fall into three basic categories (shown left to right on the infographic in their relative numbers from most to least):

- Community service officers, who are general purpose responders when a gun and the power of arrest isn’t needed.

- Crisis responders, who are specialists at dealing with mental health and related problems (this includes Seattle’s CARE team).

- Report takes and investigators, who can handle the paper work and documentation of after the fact theft reports and processing accident scenes.

These are all proven and successful roles just waiting for the right leadership to deploy (in the right numbers) here in Seattle.

Each of these roles cost less than sworn officers. At maximum step, CSOs in San Jose make 55% of a sworn officer’s salary. Denver report technicians make 75%. And CARE workers here make 87% (that’s prior to Harrell’s latest pay raise for SPOG members and not counting sworn Seattle officers’ longevity and body camera pay).

Civilianizing: good for good cops and bad for criminals

But the most important reason for civilianizing non-crime tasks isn’t financial. It’s good for good cops and bad for criminals.

Imagine an officer who chose the job for all the best reasons. She’s also been well-trained in Bill Bratton-style community policing.

So she’s psyched to have been assigned to Little Saigon, because she knows a good beat officer can make a real difference in communities that are up against it because of rampant criminal activity.

To that end, she’s doing directed foot patrol in the worst hot spot in the neighborhood when she’s called away. For the third time this week, she has to respond to 911 calls about a shouting match between neighbors over a dog pooping in the yard next door. Only this time the owner is also saying the neighbor trespassed in order to deposit the droppings on his porch.

So now on top of everything else she has to visit said porch to determine if there is indeed a smelly pile of poo there or not.

After she clears that call–at least for today–she’s diverted from getting back to executing on her anti-crime game plan by another call.

A homeless woman who is a frequent flyer for mental health episodes is lurching around a 7-11 parking lot crying and screaming for help finding her baby (which she’ll need to be reminded she doesn’t actually have).

At first she’s relieved because the CARE team will take care of it.

But then there’s a second 911 call: the woman has entered the store and is limping through the aisles wailing. So now the officer has to respond as well because CARE’s not allowed to handle the exact same situation on their own if it’s inside a building instead of outdoors.

When she hopes she’ll finally be able to return to where her beat needs her most, she’s diverted to a car crash.

Instead of following up on local business owners’ complaints about sketchy characters gathering in a parking lot after sunset and scaring off customers, she spends the rest of her shift taking he-said, she-said statements about a car running a red light and photographing skid marks on asphalt.

This is an illustration of a triple whammy of crummy.

First, it wastes public safety dollars that could be better spent (including as described above, adding more police officers, rewards for excellence at community policing, or both) by over paying for handling the non-crime calls.

Second — and worse for the officer — it needlessly randomizes the officer and interferes with carrying out a focused deterrence strategy based on time, location, and people.

Good beat officers exploit three criminological facts (assuming they’re freed up to do so). First: crime clusters geographically, with about 10% of locations accounting for 50% of crimes. Second: a few offenders commit a disproportionate amount of crime (also about 10% and 50%). And finally: deterrence is a function of the perceived likelihood of getting caught.

So if you can raise the fear of getting caught in the worst bad places and among the worst bad guys, you can make a real difference on your beat.

Third and every bit as important: we all only have so much gas in the tank for doing hard work every day. We’ve bogged her down, body and mind, in stuff that doesn’t need to be her problem, tiring her out for tackling what motivated her to take the job in the first place.

A vote for Harrell is a vote to deprive Seattle police officers of the opportunity to have more focused and fulfilling jobs like those in Orange County, San Jose, Denver, and the other cities referenced in the infographic.

At the end of the day, sworn officers are the only municipal employees we have trained and equipped to deter, confront, and arrest determined or violent criminals.

If we’re serious about making Seattle a bad place to be a bad guy, the very best thing we can do is to invest in freeing sworn officers to spend every bit of time, talent, and energy on doing just that.

A few words about SPOG

Existing labor agreements between the city and the Seattle Police Officers’ Guild (SPOG) make it possible for SPOG to obstruct civilianization.

But I want you to consider what that would mean in relation to these proposals.

Standing in the way of Seattle getting more officer hours per year devoted to proactive police work and handling crime than the city’s ever had is straight up pro-criminal.

Standing in the way of Seattle police officers getting big rewards for excellent community policing is straight up anti-good cop.

There’s no middle ground.

If SPOG isn’t willing to do the right thing and lead, follow, or get out of the way, it needs to be pushed out of the way.

A city charter amendment could reboot public safety in Seattle. (An option referenced by Seattle Councilmember Andrew Lewis in 2023 during the Harrell administration’s sluggish rollout of the CARE team).

State legislative action could make civilianization non-bargainable provided no presently employers officers are losing their jobs. (As it should be: the city does not have to bargain with SPOG to hire civilian mechanics to service cruisers or civilian accounting clerks to process payroll, even though using sworn officers to do those jobs would increase the raw number of sworn officer jobs.)

SPOG shouldn’t be allowed to prevent law abiding Seattle citizens and Seattle’s best police officers from having nice things. A better mayor than Harrell would have started tackling this issue on day one in office.

But it’s not too late to change course this election day.

A Note on Bratton’s Pivot from “Three R’s” to “Three P’s”

As a police chief, Bratton was willing to tackle a big problem facing the profession head-on. By the 1970s U.S. police departments had committed to a strategy of reacting to 911 calls, random patrol, and reactive investigation — or the three R’s. And in his own words: “Clearly, what we were doing was not working.”

Community policing emerged from police leaders, academics, criminologists, and elected officials thinking about what could be done differently. Its strategic principles were, instead, “partnership, problem-solving and prevention.”

The glass half full take is that on his watch (and many other places) community policing was effective at reducing crime and fear of crime. The glass half empty is that since its heyday in the early 1990s, many police departments–including New York City’s and New Haven’s–went back to the old way of doing things.

To this day there is still a tug of war in the profession between advocates of community policing and those who prefer the old ways.

Bryan Kirschner

Bryan Kirschner works in technology and lives in Wallingford.