Permit fees at the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) are set to go up next year, in a move that department officials are calling a direct response to a “structural change” in building activity in the city. The fee hike, which adds an 18% increase on top of a 6.5% adjustment for inflation, was adopted yesterday by the Seattle City Council’s budget committee. It comes at a time when the number of new homes entering the development pipeline remains low compared to historical levels.

The fee adjustments are intended to stave off significant budget cuts at the department and stabilize its revenue, which is 90% dependent on collecting permit fees from builders. Even so, the budget sunsets or defunds around a dozen full-time positions at SDCI. Those staff reductions come on top of cuts enacted last year.

Without adjusting fees up, the department’s core staffing reserve would be on track to be completely exhausted by the end of 2026, with SDCI’s overall permit fund at risk of depletion by 2027 or 2028.

With the adjustments, a homeowner looking to build a 500-square-foot backyard cottage will pay an additional $543 for permits, and the developer of a 230-unit apartment building will pay an additional $50,000, approximately. And as SDCI officials explained to councilmembers Monday, the adjustments signal a broader recalibration of the city’s construction market, as fewer large commercial office buildings and high-rise residential projects move forward — projects that bring in higher permit fees under the city’s tiered fee structure.

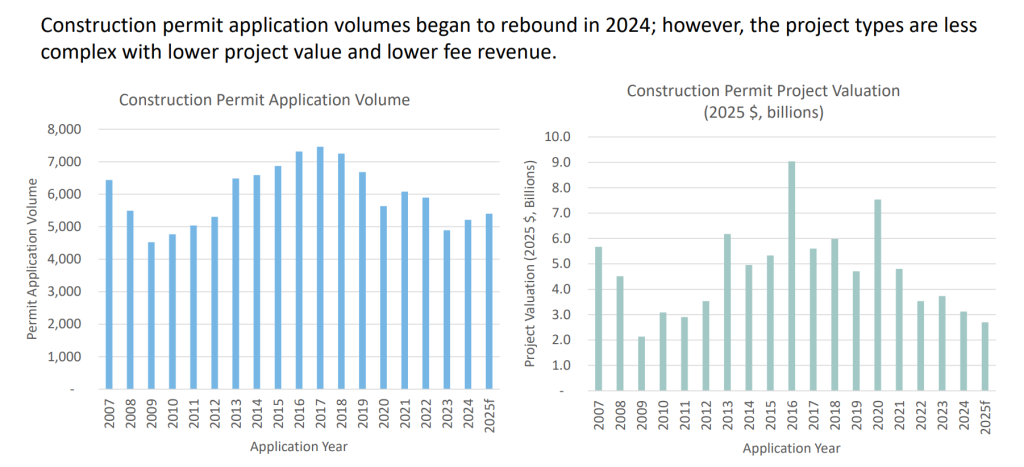

“Over the past decade, we’ve seen a lot of larger, high-value projects coming in the door, which brings in a lot more revenue compared to smaller and mid-sized projects, and it has sustained us quite a bit over the years, but there’s a structural change in the types of projects coming in the door now,” SDCI finance director Shane Muchow told the Council. “So, we have a lot of these smaller and mid-sized projects coming in the door, and the amount of revenue that we are earning from those projects is not enough to cover the cost of doing business.”

While the number of construction permits issued by SDCI has been rebounding in recent months after reaching a low point in 2023, the valuation of those permits has not been rebounding — a fact that reflects the dearth of larger projects that had been commonplace in the city. Fewer construction cranes downtown ultimately meant that SDCI needed to find a way to recoup more revenue from lower-value permits.

If the boom in smaller housing projects prompted by recent changes to encourage development in the city’s lower-density zones actually materializes, that structural imbalance may very well continue indefinitely, with the city’s commercial building market showing no signs on an uptick in the near future.

“We historically tied the cost of that permit to the value of the project, because that was seen as essentially a proxy for the relative complexity, a proxy for the amount of time,” Central Staff Director Ben Noble said. “As it turns out, we were probably, in some sense, overcharging the big projects — they were a source of revenue that helped keep the fees down for the smaller projects. Larger projects have gone away, on the whole, so we are now left to recover fees from a smaller set of projects that have less value.”

Monday’s procedural vote to increase the permit fees ultimately passed only on a 5-3 vote, after concerns were raised by Council President Sara Nelson and Councilmember Maritza Rivera. But coming on a final day of procedural votes ahead of a final committee vote Thursday, the ability to avert the change — without unbalancing the carefully assembled 2026 budget by millions of dollars — was limited. (Mark Solomon joined Nelson and Rivera in voting no.)

“It is a really hard vote because I don’t like saddling the projects that are least in a position to absorb these costs than the bigger projects that are in a better position to absorb the costs,” Rivera said Monday. “This is really it’s difficult. We’re trying to incentivize more development across the city. Everything’s getting more and more expensive, and that just makes it hard. And to pretend it’s not hard […] does a disservice.”

At a September 30 budget work session where SDCI officials presented the draft budget, it was Councilmembers Alexis Mercedes Rinck and Debora Juarez who flagged the fee increases. However, no subsequent budget amendment attracted enough to support to advance throughout October.

“This is a small drop in the bucket for a lot of projects. I think what they’re looking for are reduced interest rates, better economic conditions, more macroeconomic changes that can help drive the development,” Muchow told Juarez, in response to a question about whether the city expects its permit fee increase to broadly impact the viability of building projects. “I don’t think that this is going to affect that.”

Nelson, who is set to leave office at the end of the year, suggested that funding to offset the increases should come from “underspend,” or dollars that are left at the end of the year when departments aren’t able to fully allocate them to projects. The underspend at the city’s Office of Housing has been a particular target for Nelson, despite the fact that many of the large, complex housing projects funded by the City would not move forward without the dollars put in by the city on a “first-in” basis. While the underspend at a specific department might be significant in a given year, those dollars carry forward to fund their intended purpose and diverting them away would ultimately impact City services and commitments.

“What I think is good policy is sending the signal that we want more economic activity in this town. We want more building. We want more housing, etc. And so to me, this is sending the wrong signal at precisely the wrong time,” Nelson said. “Meanwhile, we know that there are $10 million regularly in the underspend. And so to me, it seems as though we really do have to prioritize both our human capital and the future of this city and wanting to attract more business growth in building and housing and so that is, that’s just where I’m coming from.”

Ultimately, the hope is that with the larger permit fees, SDCI can maintain its staffing levels through until the city’s next building boom — a prospect that looks dimmer and dimmer as the clouds of a potential nationwide recession on the horizon continue to gather. Even with the $8 to $9 million added to SDCI’s coffers under current projections, the department is still set to use up more than $10 million from its reserve fund in both 2026 and 2027.

“SDCI recognizes the historical cyclical nature of the building business. So in good times, it very purposely builds up reserves, potentially very significant reserves,” Noble said. “These cost centers are running in the red. We are spending more on the staff than we are taking in fees right now, and we are running down those balances. We are doing this very purposely to keep — I’m going to invoke some economist-speak here — to keep our human capital. So we have a bunch of City folks who are very well trained in this work. And if we let them all go during slow times, when the better times come, we have to go find them again, maybe not the same people, and then retrain them.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.