Road to Nowhere author Emily Lieb is speaking at Elliott Bay Books on November 20.

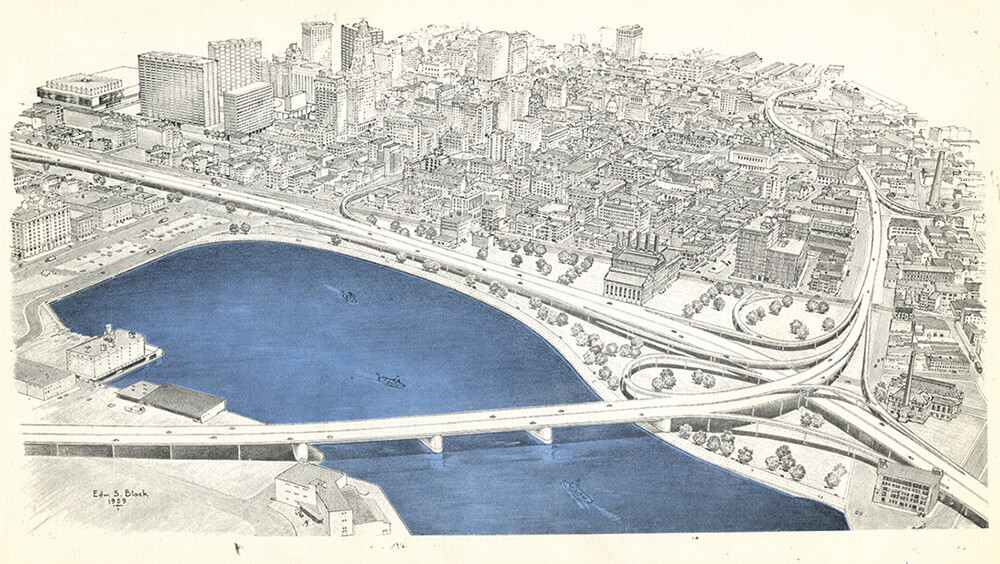

Much has been written about the negative effects of urban highways in the U.S., but they mostly focus on neglect, displacement, and gridlock that are consequences of completing the projects. Local author Emily Lieb’s new book, “Road to Nowhere: How a Highway Map Wrecked Baltimore”, shows that you don’t even have to build a highway in order to scar a city; you only need a map and some patience. Automobile proponents’ persistence pays off, literally, because their friends are able to make an obscene amount of money along the way.

Despite the book’s title, the 10-D highway, the East-West expressway that was supposed to revitalize downtown Baltimore to better serve its suburban population, plays only a supporting role in the story. The main character is Rosemont, a middle-class neighborhood in West Baltimore. The book begins with Rosemont’s transformation from an exclusively White working-class neighborhood into a Black, but still middle-class neighborhood thanks to the city’s segregated school system.

The author dives into all aspects of the neighborhood’s deterioration and stagnation over almost 40 years while it was held hostage to constantly changing highway plans before the project was eventually canceled in 1981. Finally, she describes how Baltimore officials made an insincere attempt to restore the neighborhood to its pre-expressway-imagined state with the help of federal money. During all three stages, fortunes were made – not by Rosemonters, but by real estate speculators, money lenders, contractors, and politicians – while Rosemont itself didn’t see much investment.

Together, this makes “Road to Nowhere” a good introduction into how local and federal policies and interests shaped not only this part of Baltimore but many other, usually non-White neighborhoods in other cities across the country. The sprawling ramps of I-5 and I-90 in Seattle’s International District would not have been possible without the Federal Highway Act’s generous funding, the same federal program that made Baltimore’s politicians look seriously at the plans for 10-D.

On top of bad transportation policy, the Federal Housing Administration’s Section 235 program, which guaranteed mortgages for low- and moderate-income homebuyers, became a source of financial ruin for many Rosemonters who were lured into unknowingly buying condemned houses after the highway project was put on hold. The fiasco was a national scandal in the 1970s.

There were many factors that led to the eventual withdrawal of the highway project, including an oil crisis and the concurrent rise of environmentalism, but it was the loss of funding that proved decisive. The city’s tax base had declined, the state was getting less money from its vehicle excise tax, and the federal gas tax was too low to continue building at the pace of the 1950s and 60s. At the same time, highway costs were rising, in part due to environmental regulations and the new road design standards requiring a larger footprint.

Rosemont’s story also serves as a sad reminder that activism isn’t always enough. Even though, on paper, opponents of the highway won, their fight dragged on too long, and the consequences have lasted to the present day.

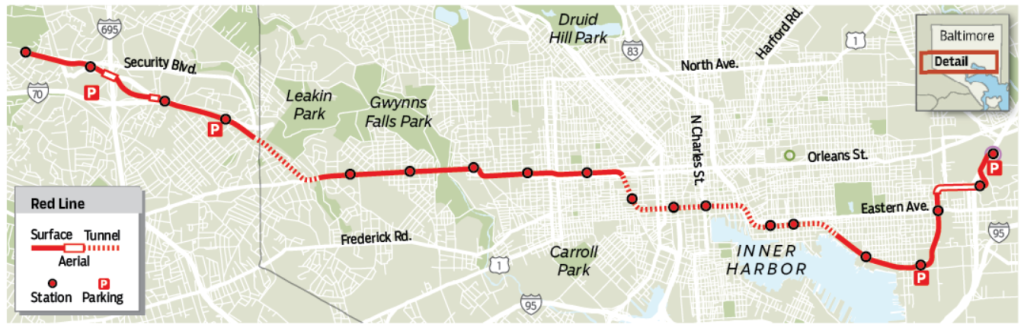

As dismal as the account is, the book ends on a positive note, reporting on a future light rail project, the Red Line, which, after some drama of its own, is in its planning phase. It is intended to reconnect the neighborhood and breathe new life into Rosemont, this time for real – that is, if funding comes through.

Elliott Bay Book Company is holding a discussion of “Road To Nowhere” with author Emily Lieb on November 20 at 7pm.

Valentina Vaneeva

Valentina Vaneeva enjoys reading books, learning languages, and taking photos of her friends. She grew up in Russia but has been living on the Eastside for more than a decade.